False Facts About Soy Sauce You Thought Were True

Soy sauce is the potently flavored liquid condiment that we know, love, and use extensively in restaurants and home kitchens. It is closely related to miso, and bears a strong resemblance to other fermented products from Asian culinary traditions. At its core, soy sauce is a simple product primarily made from soybeans, yet the end product is a concentrated sauce teeming with a myriad of flavors and aromas, including the seductive umami punch. Most Asian cuisines rely heavily on soy sauce, but its potential has been recognized worldwide, and is no longer strictly confined to its origins.

Like many products adopted by Western culinary traditions, there are numerous misconceptions about soy sauce, including its origin, production, health aspects, and culinary uses. This article aims to dispel some of those myths we've come to believe — whether through innocent misinformation, or specific agendas — and presents a genuine portrayal of soy sauce as an incredibly complex ingredient that can transform dishes in any home kitchen.

False: Japan is the birthplace of soy sauce

Though Westerners became familiar with soy sauce in the 20th century, its origins are ancient. Despite the common misconception that it originated in Japan, it is believed that soy sauce first appeared in China, and its ancient predecessor was a thick fermented paste known as jiang. These pastes were already familiar during the Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 B.C.). They were made with various ingredients, including meat and seafood, but grains and soybeans proved to be the most suitable options, and gave it a contemporary form. The process also created a byproduct — a rich-flavored liquid called jiang you that was left after the beans were pressed. Of course, jiang you is what we today know as soy sauce.

It is estimated that jiang was brought to Japan during the Yamato Era, probably sometime in the sixth century, coinciding with the introduction of Buddhism. The Japanese adopted the idea, and started producing versions that would become miso paste. The liquid created in the process was called tamari, a name still used for soy sauce versions created with 100% soybeans. This eventually led to shoyu, the collective name used for all Japanese soy sauces. People often associate soy sauce with Japan, as the country has mastered the art of making it, and produces a great number of varieties. Also, it became a go-to option in the U.S. due to military ties and the growing popularity of Japanese food in the second half of the 20th century.

False: Japan and China are the only countries producing soy sauce

Though we mainly associate soy sauce with Japan and China, likely due to the vast number of available varieties, its production is not confined to these countries. As a quintessential condiment, many Southeast Asian countries produce their local versions that align with traditional practices.

South Korea has one of the longest histories of soy sauce production. Locally known as ganjang, the sauce is made in several different styles. Kook-ganjang, or soup soy sauce, is the traditional version with a much saltier kick, while jin-ganjang is the most commonly produced commercial version, and the classic workhorse in the kitchen. The Indonesian take on soy sauce is quite unique, as it combines soy sauce with a mix of water and sugar to create a thick, dark sauce with plenty of sweetness. It is usually labeled as kecap manis, while the less common and less sweet type is called kecap asin. Thai soy sauce is similar to Chinese soy sauce, but they also produce several versions, including those laden with sugar and mushroom-flavored sauces. Taiwanese soy sauce is distinct, and best known for its traditionally produced variety, which uses only black soybeans. In the Philippines, where it is known as toyo, the sauce is typically darker, stronger, and saltier, and is mainly used for cooking.

Surprisingly, there's even a soy sauce factory in the U.S. Kikkoman operates two facilities in the States, and there's even a local soy sauce factory in Hawaii.

False: There is only one variety of soy sauce

While most labels display only the generic "soy sauce" moniker, those less familiar with Asian cuisine might mistakenly believe there is only one style of soy sauce. The vast number of regional varieties clearly contradicts this assumption.

A key distinction to note is between Japanese and Chinese-style sauces, as these are the most prevalent. In Japan, the main differentiation is between light and dark shoyu, with the latter being more popular nationwide, and typically found in Japanese restaurants. Japanese soy sauces often maintain an equal ratio of soybeans to wheat, resulting in a lighter flavor profile with a noticeable grainy sweetness. In China, the soy sauce hierarchy is less rigid, but there's a general focus on classic light soy sauce and a thicker, sweeter dark variant. Additionally, one might encounter mushroom-flavored and sweet soy sauce varieties. Acknowledging the diversity of regional styles, it's evident that soy sauces are far from uniform, and encompass various distinct styles.

Understanding these varieties is important not only for personal taste and preference, but also for culinary application. For example, Chinese light sauce is a great condiment, while the dark version is better suited for cooking. Similarly, you don't want to dip your elegant sushi in a sweetened or mushroom-flavored variety, or to allow the subtle flavors of light soy sauce to be overwhelmed in a stir-fry.

False: All soy sauce tastes the same

Considering the regional differences and the vast number of styles, the most erroneous assumption about soy sauce is that it all tastes the same. Though soy sauces can vary in texture and color, the most significant difference lies in flavor, and this should be the guiding principle when selecting a bottle for your next culinary endeavor.

The first aspect to consider is the character of the dish. For heavy braises and stir-fries, dark Chinese-style sauces are suitable, as they blend saltiness with a dominant sweetness, and their multilayered character won't get lost during cooking. These dishes also pair well with Korean jin-ganjang, or any sweet soy sauce, like Indonesian kecap manis, which boasts abundant caramelized and molasses-like flavors. If you're using soy sauce as a seasoning or marinade, opt for Korean guk-ganjang, or light Chinese sauces that feature predominant saltiness. For the most nuanced flavors, choose light Japanese sauce, known as usukuchi. This sauce is light in color, rich in complexity and umami flavor, and best suited for lighter dishes.

For an excellently versatile option, Japanese koikuchi, or dark soy sauce, is highly reliable. It's readily available in stores, and can be used as a dipping sauce or to season sauces, soups, and broths.

False: There are no gluten-free soy sauce varieties

Soy sauce is typically produced with five ingredients: soybeans, wheat, salt, koji mold, and water. This means that most soy sauces are not gluten-free, as even a minimal amount of wheat can render it unsuitable for those sensitive or intolerant to gluten. Fortunately, not all styles fall into this category. For those looking to avoid gluten, the safest option is to opt for Japanese tamari, a variety that traditionally does not use wheat. It is believed that tamari is the earliest form of Japanese soy sauce, and that wheat was only later added to traditional recipes.

What's great about tamari is that it's an exceptional and versatile variety of soy sauce. The use of 100% soybeans results in a sauce with a wonderful texture and a distinct flavor profile that is assertive, yet not harsh or overpowering. This makes tamari an excellent cooking ingredient for sauces, ramen, stir-fries, and soups, but it's also great as a dipping sauce. To be extra cautious, always read the label to ensure that the tamari is made with 100% soybeans.

In addition to tamari, some brands may not use this specific labeling, but will instead label their product as soy sauce, adding a gluten-free designation. These products are also widely available, and even major brands include them in their selections, so finding them should not be an issue.

False: Teriyaki and soy sauce are the same thing

You've likely encountered teriyaki sauce among the myriad Asian-inspired sauces that populate the shelves of most large supermarkets. In the bottle, teriyaki shares many similarities to regular soy sauces — they have the same dark, robust color and, depending on the soy sauce type, a comparable texture. Many mistakenly believe they are identical and can be used interchangeably, but while we might consider them distant relatives, they are two distinctly different ingredients with unique flavors and culinary applications.

The concoction we commonly recognize as teriyaki sauce nowadays is a blend of soy sauce, mirin, and sugar, though you'll also encounter variants flavored with garlic, ginger, sesame, or even enriched with pineapple juice. The sauce typically has a thick texture, and some manufacturers add cornstarch to achieve the desired consistency. In general, this sauce offers salty and intensely sweet flavors and, just like soy sauce, is packed with umami. Because of its rich texture and high sugar content, teriyaki is mainly used as a cooking ingredient, ideal for glazing and creating marinades. While teriyaki can serve as a dipping sauce, you should reserve it for items like spring rolls or dumplings. It's not recommended to pair the bold flavors of teriyaki with delicate and nuanced dishes, such as sushi.

False: There are not many ways to use soy sauce

Soy sauce is commonly associated with sushi and sashimi, but this complex condiment should not be confined to a single use as merely a dipping sauce. Various soy sauce types can be utilized in several ways, revealing more culinary potential than we might initially realize.

At its essence, soy sauce is a salty ingredient, so definitely consider using it as a regular condiment. It will deliver not only a salty kick, but also an umami richness that can enhance any dish. Think outside of the box, and incorporate the sauce into a ground beef mixture, add it to classic creamy soups, or even mix it into your scrambled eggs. Soy sauce is a staple in marinades, but it can also enhance your favorite salad dressing. When preparing a hearty meat sauce or an Italian-style ragù, a dash of soy sauce can introduce additional complexity and depth.

For a truly unconventional application, add soy sauce to your desserts. It pairs exceptionally well with chocolate-heavy recipes, where it can amplify the deep cocoa flavors. Consider adding a splash to salted caramel. In one of the more recent culinary trends, soy sauce is used as the perfect finishing touch on vanilla ice cream, offering a unique twist.

False: Soy sauce is high in calories

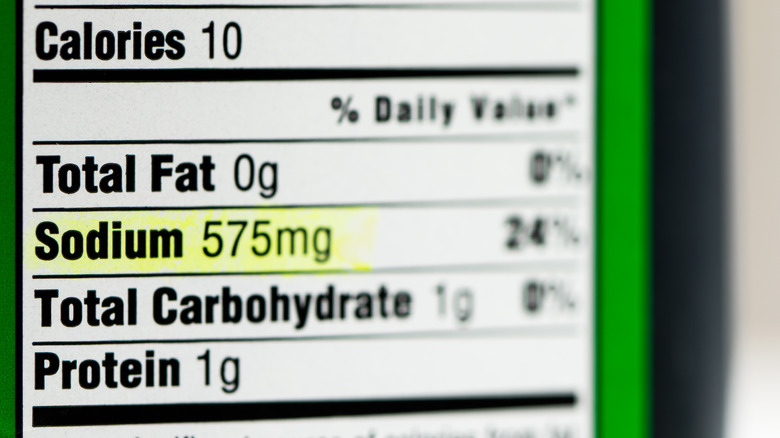

Soy sauce is sometimes mistakenly considered a high-calorie ingredient, but a closer look at the nutrition label on any bottle will reveal a different story. One serving of soy sauce, which is equivalent to one tablespoon, tends to contain between eight to 10 calories, which is relatively minor compared to most recommended daily caloric intakes.

However, soy sauce does present some concerns regarding its sodium content. While the exact amount can vary by brand, a typical serving often contains around 1,000 mg of sodium, which is about 40% of most recommended daily maximums. Fortunately, a small amount of soy sauce can significantly enhance flavor, so you don't need to use a lot. Nonetheless, if you have health considerations that require limiting sodium intake, it's crucial to be mindful of the quantity you use. Opting for low-sodium soy sauce varieties could also be a beneficial alternative.

False: You should avoid soy sauce, as it is packed with MSG

Monosodium glutamate, or MSG, is the additive that was associated with the discriminatory term "Chinese restaurant syndrome," a biased theory positing that MSG's heavy use in Chinese restaurants led to various health issues, including chest pain, palpitations, headaches, and sweating. Originating in the 1960s, this racist myth long tarnished MSG's reputation. However, these theories have been debunked, and MSG is now recognized as safe, though it is still sometimes stigmatized by the public.

Scientifically, MSG is the sodium salt of glutamic acid, chemically produced and typically used as a food additive. It appears as tiny crystals that resemble table salt. You'll usually find MSG in processed foods like instant noodle soups, snacks, and pre-mixed sauces, where it's added to help flavors pop. Glutamic acid also occurs naturally in foods such as tomatoes, anchovies, miso, and authentic Italian parmesan. Unsurprisingly, it's present in soy sauce as well. Any naturally brewed soy sauce will contain some glutamate, but some varieties add MSG to increase the umami richness.

Our bodies break down glutamate and MSG in the same manner. Essentially, MSG is not an ingredient to fear if used in moderation. It's simply a flavor enhancer that imparts a savory note and a hint of umami to food.

False: Soy sauce needs to be refrigerated after opening

We often assume that soy sauce, like most jarred and bottled products, must be refrigerated after opening. While you can store an opened bottle of soy sauce in the fridge, it's likely unnecessary, and the decision to leave it out in the pantry hinges on several factors.

If you're a soy sauce aficionado who consumes the bottle rapidly, you can skip the refrigeration, since the soy sauce won't have time to spoil or develop mold. However, if you're not a frequent user of soy sauce and that small 15-ounce bottle sits unused for months, it's wise to keep it in the fridge. Although brands often note that soy sauce be refrigerated, it's a relatively stable product thanks to its high salt content and the common use of preservatives. Refrigeration becomes more crucial with refined, high-end soy sauce varieties, where the cool environment better preserves their delicate nuances, maintaining freshness and protecting aromas and flavors.

Regardless of storage, you should always shield soy sauce from sunlight and heat, especially if it's packed in plastic bottles — glass is slightly more resilient. Sun and heat are soy sauce's worst enemies, and they will rapidly accelerate its deterioration.

False: Chemical soy sauces are equally good

The traditional method of soy sauce production involves fermenting soybeans with wheat and koji mold, then mixing this with salt brine — a process that can take months or even years before the sauce is ready for extraction and pasteurization. When soy sauce became popular, a less nuanced technique emerged. This method employs chemicals and simplified processes, but while the end product may look the same, it can't match the quality of traditionally made soy sauce varieties.

Producers opt for artificial soy sauces to reduce costs. They typically utilize food grade hydrochloric acid and soybeans, heating the mixture to break down proteins. The sauce is then neutralized, filtered, and adjusted with additives, and can be ready in just a couple of days. However, this sauce poorly mimics the authentic character of traditional soy sauce. It comes off as one-dimensional and flat, lacking the finely tuned complexity and intricate flavors of traditional sauces. These sauces can be easily identified by reading the label, which often includes ingredients like caramel and corn syrup. These artificial sauces are never an ideal option. Traditionally brewed soy sauces, now widely available, not only pay homage to the rich tradition and ancient craft, but also ensure you are consuming the finest product available.

False: Soy sauce is reserved for Asian cuisine

Although we typically associate soy sauce with Asian cuisine — particularly intricate sushi and sashimi platters, or flavor-packed fried noodles — it is a versatile ingredient whose attributes have been recognized beyond the Asian continent. This condiment is now widely used in various countries worldwide, with Mexican cuisine boasting a particularly rich soy sauce tradition.

In Mexico, soy sauce, known as salsa de soya, was adopted and integrated into local cuisine. Its popularity can be traced back to the 1800s, when a significant number of Chinese immigrants arrived in the country for work. The influx increased at the turn of the century, largely due to the discriminatory Chinese Exclusion Act passed in the U.S., which restricted the number of male Chinese immigrants. These workers then turned to Mexico as an alternative. Naturally, they brought their traditional food and products with them, including soy sauce. As Chinese immigrants settled, particularly in the north near the American border, they began opening grocery stores and restaurants. Inevitably, this led to the emergence of a new fusion cuisine that blended local and foreign influences, creating novel dishes, and infusing some classic recipes with new flavors.