Little-Known Facts About Alice Waters

In the last 10 to 20 years, it seems like farm-to-table restaurants have popped up in every corner of the United States. The rustic yet chic restaurants promise fresh eating sourced from local farms and seasonal ingredients to any hungry guest who steps through their doors. Sure, maybe this could be written off as some passing trend, but lifestyle companies like Riise believe that farm-to-table transcends contemporary fashion. The organization points to the food movement as representative of a larger reassessment of culture with climate change in mind. In that sense, the slow food movement — think of it as the antithesis of fast food — could very well represent the future of eating while also getting back to basics.

While the food philosophy of local ingredients prepared well and used seasonally may seem obvious as can be, it can be traced back, in the mainstream at least, to California cuisine. As defined by Masterclass, this style of cooking is defined not only by seasonality and freshness, but also by locality and creativity with said ingredients. Simply put, California is known for taking the resources it has at hand and preparing them to the best and healthiest extent that they can be. In this sense, there is no better representative of California cuisine, and the farm-to-table movement, than chef Alice Waters, who is often credited with being the pioneer, if not founder, of the movement.

Waters was heavily inspired by her time in France

For someone who has become one of the biggest luminaries in American cuisine, Alice Waters actually got her start far away from the American kitchen. According to Encyclopedia Britannica, Waters first studied French culture at the University of California, Berkeley, and it was these very studies that would take her to France for some time abroad. The now-chef had by all accounts no formal training in the culinary world, but Taste describes her time in France as nothing short of an "awakening" for the living legend. It was the French attitude surrounding food that would shape Waters' unique ideas.

While abroad, Waters was particularly fascinated with French markets, where produce and foods were sold fresh and in an open-air environment, per Taste, which included an except from Waters' 2017 book, "Coming To My Senses." At the time this differed greatly from American supermarkets where frozen food aisles dominated. As a college student Waters fell not only in love with French dishes, but also French ingredients. Long after she returned to the West Coast, Waters still craved the same high quality she had grown accustomed to in France and began seeking out co-ops, farmers' markets, and specialty shops. With a friend, she began running a newspaper column where they would explore recipes and make every dish by hand, according to Taste. It was the beginning of what would define a generation of food.

She taught preschool before opening her first restaurant

In between college graduation and her later career as a chef, Alice Waters became a teacher for a short period of time. As noted by the chef herself in an excerpt of her book reprinted in The Guardian, she concedes that she was unsure of what to do with her life. She enjoyed her food column and had a dream of starting a French bistro but admitted that opening a restaurant felt impossible.

Ever the radical, Waters found herself drawn to Montessori-style teaching, which emphasized learning by doing. With an internship at a school in Berkeley followed by a 9-month training program in London, Waters found her mindset and approach to work heavily influenced by Montessori-style teaching. Food was almost always prevalent in Waters' teaching style. During her time at Berkeley's Martin Luther King Jr. Middle School, she started The Edible Schoolyard Project, where students could create a relationship to food while also reaping the very literal fruits of their labor (via The Aidan School).

Through teaching, Waters internalized that the care one puts into work creates a unique beauty in itself, per The Guardian excerpt. It's very well that she carried over this compassionate attention to detail to both her restaurant and her meals. One former Montessori school student who later worked as an adult with Waters notes in The New York Times that a simple egg she cooked for him was so good that "for that fleeting instant, I felt loved."

The chef philosophizes that food is a way of life

As she entered the culinary scene, Alice Waters stood — intentionally or not — in direct opposition to the popular fast food movement, as described by The Culture Trip. The chef, as noted in the article, staunchly believed that the best kinds of meals are the ones that take time. In Waters' world, dishes are made from produce harvested by farmers whom the purchaser could theoretically meet. These meals are then prepared by hand at home with no drive-thru and as little packaging as possible (via The Culture Trip).

But this isn't just surface level. Somewhat esoterically, the article notes that Waters truly is a proprietor of the age-old adage: You are what you eat. Waters is noted to believe that our literal values go all the way down to the roots of what we eat. With that, she means that the goodness of what we eat can influence how we carry ourselves in the day-to-day and how we treat the world around us. For the chef, a sustained environment, a good life, and the dinner plate are all intertwined. There's certainly a lot of thought and emotion put into it, but no one can deny the resonance and effect that Waters has had. It's no surprise that in 1996, The New York Times named her a food "revolutionary."

Alice Water's cooking philosophy inspired Michelle Obama

Like Alice Waters' concept for The Edible Schoolyard, the idea for a garden soon made its way to the White House. In 2009, following the election of President Barack Obama, Waters wrote an open letter addressing both him and First Lady Michelle Obama, urging them to include whole foods in their domestic policy. Waters even offered to form an advisory team to help find a White House chef who could focus on local, in-season and domestically grown produce for the official White House menu. Equally tremendous in significance, she proposed her long-held vision of cultivating a vegetable garden on the White House lawn. This move, she noted, would not only be a nod to the victory garden planted during the Second World War, but would also beautifully embody the Obamas' dedication to nutritious and holistic eating, according to the letter.

In the summer of 2009, Michelle Obama started the first vegetable garden on White House grounds since Eleanor Roosevelt's own garden (via The New York Times). But, this plot wasn't just for show, as the article observes. Its produce would be harvested for both formal and informal meals served to the first family. Interesting to note is that like Waters, Michelle Obama envisioned the garden as being a place of active learning for visiting school children, according to the article.

In 1971 Waters opened the renowned Chez Panisse with a unique vision

Arguably, Alice Waters' magnum opus is her restaurant, Chez Panisse, which first opened its doors in 1971. The Culture Trip goes so far to describe the restaurant as the perfect embodiment of Waters' approach to food. While some may shrink at the idea of a $12 fruit bowl, for example, the site assures that the quality is enough to sway even the most dubious.

While the restaurant may be synonymous these days with California chic and elevated dining, Waters describes the restaurant's opening night as a bit more ramshackle in an excerpt of her 2017 book that appeared in The New Yorker. The upstairs had not been completely renovated, and she recalled still fastening down carpet as the first diners arrived. From there on, the restaurant stayed packed and bustling throughout the night. Waters notes that a waitress made sure to keep wine glasses full to encourage guests to stay as long as possible while they waited.

The legendary chef was not even behind the stove that night, as she entrusted a friend to cook while she manned the floors. Waters noted that the restaurant filled with people from different California scenes: Filmographers, writers, political activists, designers, and musicians not only came the first night but also went to define the scene surrounding the restaurant at this period in time. It was just as much the people as the food that imbibed the restaurant with its own unique magic.

Chez Panisse still operates to this day with a rotating menu

There is evidently staying power behind Alice Waters' philosophy, as Chez Panisse is still serving up seasonal delights five days a week in its original location. While the menu rotates daily, at the time of this writing, one could expect to spend about $175 for the prixe fixe menu that's sure to provide the best of what the season has to offer. While it's been more than a half-century since the restaurant's opening, there's still an element of mystery, or as described by the San Francisco Chronicle, "fantasy," surrounding the now storied eatery in Berkeley.

Like many, the journalist from the Chronicle who visited Chez Panisse in 2019 was already more than aware of Waters' vision and was respectful of the slow food movement as a whole. But, the writer was quick to observe that it's Waters' impact and legendary status that detract from the food being served there some five decades later.

As she so pointedly asks: How can you possibly talk about the food when it rotates so frequently and has almost become symbolic in meaning? Now that slow food and natural foods have become the supposed norm for restaurants and even fast food joints, perhaps the sheen from Chez Panisse has dimmed, if only just by a little. Nonetheless, the writer placates those who would like to sit where history has been made and enjoy a truly wonderful meal, saying they will not be disappointed.

Her neighborly relations haven't been all positive

Despite Alice Waters' important role in the food movement, she hasn't been without controversy. Her famed Chez Panisse had a next-door neighbor, the César tapas bar, which first opened in 1998 (via San Francisco Chronicle). According to the Chronicle, Waters had been leasing the space to the restaurant and opted to let the lease expire in July 2022 in favor of opening a new venture there herself.

The choice to not to renew César's lease caused mixed reactions among locals. Those mixed feelings were further complicated by the history of the two restaurants. César opened as a compliment to Chez Panisse with its comprehensive cocktail bar and delicious finger foods to whet the appetite of diners as they headed next door, as per the Chronicle. The restaurant was even co-founded by Waters' ex-husband. Dedicated César fans took to the streets, albeit "politely," to protest, as described by Berkeley Side.

Partially organized by César employees and devoted fans, these protesters argued that at this moment in time, when the pandemic has so greatly affected the gastronomy scene, it was especially unjust to close an establishment that meant so much to so many. Despite the anger surrounding the bar's closing, the protesters were like family and "happy" to be together, per Berkeley Side, which speaks volumes to the restaurant's importance to many.

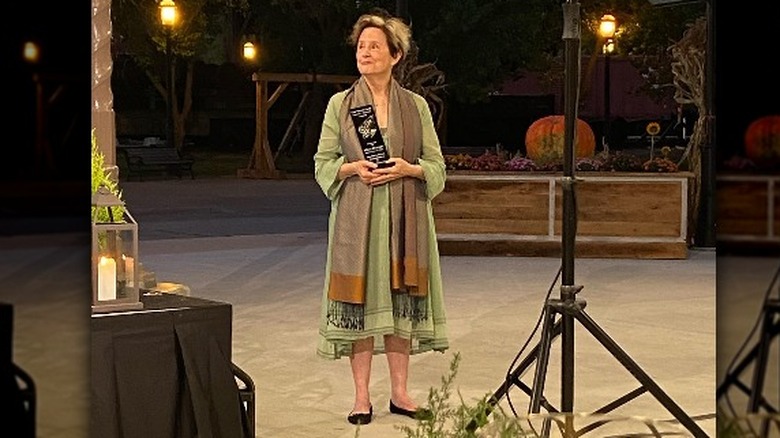

Waters was the first woman to win the James Beard Foundation Best Chef Award

There is no question that Alice Waters is one of the most meaningful chefs in America, if not the world. Through her activism both in and outside the kitchen, she has fallen into high regard among many. The James Beard Foundation Awards seek, per the organization's mission statement, to honor those restaurants and chefs that push America's cuisine to a higher level with "talent, equity, and sustainability." These are major awards — named after James Beard, an icon in the food industry — that have been bestowed upon culinary legends like The French Laundry and Jody Adams.

It was nothing short of a momentous moment when Waters became the first female recipient of foundation's award for Best Chef in America in 1992. As noted by the Chicago Tribune, the kitchen was long considered "a woman's place," but for a very long time women were barred from the professional kitchen. To honor Waters after more than 20 years of running Chez Panisse and advocating for a change in the American food industry was a long time coming. Nonetheless, it was also a major turning point for female chefs. Waters not only represented the shift in favor of slow food, but also a growing recognition (and space) for female chefs and food visionaries and their major contributions to the world.

The chef has also won many accolades outside of the culinary world

Fitting to Alice Waters' intersectional approach to food, the chef has earned more than a few accolades outside of the culinary world. In 2008, she was awarded a Global Environmental Citizen Award to celebrate her work. In 2015, President Barack Obama awarded the chef the National Humanities Medal to acknowledge her work in connecting the "edible and ethical" (via SFGate). In 2017, she was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame. While she has not been a teacher for a very long time, Waters still advocates for her Edible Schoolyard project that seeks to put students directly in touch with their diet and food at a young age (via Masterclass).

While she may not be in the classroom any longer, she has published many books, several of which have received stellar reviews. An article from the San Francisco Chronicle observes that some chefs and restauranteurs who have worked at Chez Panisse even feature Waters' much-heralded book "The Art of Simple Food" at their own restaurants to pay homage to her influence. It seems then fitting that due to her contributions to the way that people think about food, the American Philosophical Society named her an honorary member. For Waters, food isn't just a meal. It's a way of life.

The chef has faced personal criticism

But not everyone has been enamored with Waters' approach to food or agrees that she is as revolutionary as she seems. For a philosophy that focuses on slow movement and intention, Berkeley Side observes that there's a lot of hostility surrounding the chef. One criticism surrounding Waters, as outlined by The New York Times, is that she is "elitist" in both view and practice.

The common perception is that her eating style is unobtainable for those living paycheck to paycheck. And there are those who cannot justify spending $12 on a fruit bowl per se. As noted by The Breakthrough Institute, Waters defends these costs as being reflective of the sustainability and ethical working conditions gone into cultivating the produce. Nonetheless, this food philosophy remains impossible for those who either do not live in an area that has access to organic farms or simply cannot budget for it. The latter site argues that it's not the people who need to adjust their dietary habits, but rather the food system that needs to change to include every person. According to the institute, it shouldn't just be those who can afford the nearly $200 meal at Chez Panisse that should be able to eat well.

Waters is to this day an ardent food activist

Despite controversy and criticism, Alice Waters remains to this day a passionate activist for eating organically. In a time when the climate crisis has become a topic of near-daily discussion, she maintains that there is no better time for us as a country to reassess our relationship with food (via Shondaland). While Chez Panisse still remains under her stewardship and she continues writing about food, Waters maintains that the most important place to start with sustainable eating is in the school yard. Ultimately, the edible schoolyard remains at the heart of Waters' food philosophy, as outlined by Shondaland. Waters believes, perhaps now more than ever, that a comprehensive understanding of food and the importance of the environment begins in childhood.

Waters' Edible Schoolyard Project, which has been running for over 20 years, seeks to bring Waters' philosophy to fruition, as outlined by The Battery. Operated in California, the project takes inspiration from Waters' original school-based vegetable garden, which still exists to this day (via The Edible Schoolyard Project). The project builds on this to provide free, locally sourced lunches for students and give access to gardens that students may not otherwise have.

In 2021 Waters opened her first L.A. restaurant

While Chez Panisse remains the most well-known of Alice Waters' culinary pursuits, her other ventures have also made big splashes. Located at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, Waters' 2021 Lulu functions similarly to its predecessor: It utilizes a rotating menu that features simple, locally sourced food, with a prixe fixe (via Eater). Located in the open-air terrace of the art museum, one writer with the San Francisco Chronicle notes that the restaurant has a lovely ambience, which is described as equally modern and inviting.

The journalist notes for those looking to explore Waters' culinary vision at a lower price point, Lulu may be the right place to go. A three-course menu at Lulu's comes in at about $65, more than $100 less than the four-course meals featured on the menu at Berkeley's Chez Panisse. Despite the overwhelmingly positive experience, the journalist aptly takes note of a few misses at Lulu. She recommends opting for the rotating menu instead of the staple pieces, as they tended to be notably bland in comparison. She also noted that the famous goat cheese salad she sampled varied considerably when it was ordered at lunch versus when it was ordered at dinner. She went so far as to compare the dinner salad in quality to a "Disneyland churro." Nonetheless, for those looking to experience Waters' cuisine, Lulu provides a refreshed take on a California classic.