This Is How Bacon Is Really Made

Bacon: you've gotta love it, right? Arguably one of the world's most popular breakfast foods, this type of pork has, in recent years, become something of a cultural phenomenon. Otherwise known as the "Bacon Boom," the explosion in bacon's popularity cannot be ignored — nowadays, Americans alone spend just under $5 billion a year on the popular meat. A typical American consumes around 18 pounds of bacon every single year, with some surveys suggesting a majority of the country want to make bacon the United States' national food. Basically... It's pretty big.

But despite the fact that you might have eaten bacon mere hours ago, you might not actually know just how it got onto your plate. Sure, you're probably aware that it's a kind of cured pork, but how is it actually made? What type of pig does it come from? Does it have to be cured? And just how many variations of bacon are there? Well, fear not — we've got you covered. Here's how bacon is really made.

Bacon has an interesting history

Before you find out how bacon is actually made, of course, it might be useful to come to grips with its history. The first mention of anything resembling bacon dates back thousands of years to Ancient China, where it took the form of salted pork belly. Until the 16th century, the term "bacon" was used to refer to pretty much any pork you could find. The word itself derives from continental European dialects, including the Old High German term "bacho," meaning "buttock."

Bacon arrived in the New World with the Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto, the so-called "father of the American pork industry," who brought 13 pigs with him to America in 1539 and soon grew his herd to a size of 700. Unfortunately, things got a little out of hand and the New World's pig population ended up expanding so rapidly and uncontrollably that wild pigs continued to run amok in New York City as late as the 19th century.

Today, of course, Americans are doing their best to make amends for this by eating as much bacon as they possibly can. Around 70 percent of bacon is eaten with breakfast, but it's also a hugely popular sandwich ingredient and often shows up on fine dining menus across the country. But you knew that, didn't you?

The traditional method of making bacon

Okay — so here's the multi-million-dollar question: how is bacon actually made? Well, there are actually two primary methods for producing it. The first is dry curing, an older, more traditional method of bacon production.

The raw bacon you begin with is first rubbed with salt and seasonings, as a way of giving the meat flavor, before allowing it to cure for between one or two weeks. After the bacon is cured, it's rinsed off, dried, and put into a smoker to help add more flavor and increase the meat's preservative qualities. Not all bacon is smoked, however, and sometimes dry-cured bacon is hung to air dry in the cold for a number of weeks — or even months.

Because the curing process is so time-consuming, it's not often used in the United States today. That's not to say it's not available, however, and if you can get your hands on some dry-cured bacon, it's worth doing — if for no other reason than to enjoy its deeper, most robust flavor profile.

The industrial method of making bacon

Most of the bacon you eat nowadays is wet-cured, since this quicker method is far more suitable to industrial mass-production. To begin with, a number of curing ingredients — including salt, sugar, sodium nitrate, and other chemicals (more on that later) are mixed together to create a brine. The raw bacon is then injected with this brine (although sometimes it is soaked in it instead; a method known as immersion curing). Sometimes, like dry-cured bacon, wet-cured bacon is smoked for flavor. Most of the time, however, the bacon is placed in a convection oven for around six hours, with liquid smoke occasionally added to give the meat a smokier flavor.

Generally, wet-cured bacon is high in moisture and lacking in flavor. That added moisture also makes it heavier, which actually makes it more expensive. As a result, you're usually better off buying dry-cured bacon; although it may be pricier per pound, its weight comes from the meat itself rather than the water contained within. The golden rule is this: just like with pretty much every other kind of food, a higher price tag usually means higher quality. And why go halfway in on something as important as bacon?

Miracle cures make bacon better

Although bacon tends to be either wet-cured or dry-cured, there are changes and additions you can make to the curing process that result in different variants of bacon. Wiltshire curing, for example, is a type of wet-cure that involves curing the pork, bone-in and rind-on, in a special recipe brine for up to two days. After that, it's kept in cold storage for two weeks to allow it to mature — giving the finished bacon a subtly salty flavor and a meaty texture.

Maple curing is when you add maple syrup to the curing mixture (the seasoning rub in dry-curing or the brine in wet-curing). The meat is cured for up to five days and then smoked, resulting in a smokey, woody flavor with a hint of sweetness to it. You can also sweet-cure bacon, using a range of ingredients including sugars like muscavado, demerara, and molasses, and spices such as juniper. Adding this extra sugar instills the bacon with a smokey and syrupy flavor and a very sweet aroma.

These are some of the more popular variations on bacon curing, but if you're making bacon yourself you could always try experimenting — mix up your rub (or brine) with whatever ingredients you like and see what happens. Who knows what you might discover?

What you should know about uncured bacon

You might have heard of uncured bacon before, especially as a healthier alternative to regular bacon. The idea is that, because the wet-curing process involves adding nitrates to bacon meat, it can come with more health risks attached — since nitrites are often linked to higher incidences of some cancers.

Confusingly, uncured bacon isn't actually uncured; it's simply cured using celery powder, salt and other flavorings. The idea is that celery contains natural nitrites, rather than the artificial nitrites used in the mass production of bacon. The nitrates themselves are actually crucial to the way bacon is made, because they maintain flavor, prevent unpleasant odors from developing, and delay the growth of harmful bacteria.

Unfortunately, it's still not certain whether or not natural nitrates are any more or less harmful than artificial nitrites — meaning it's more or less impossible to know whether "uncured" bacon is actually better for you than ordinary bacon. Just don't fall for the marketing ploys: that fancy packaging might say you're eating uncured bacon, but the reality is you're just eating bacon that has been cured in a different way... and not necessarily a better way, either.

Chemicals and additives in your bacon

As with many mass-produced foods, bacon (or at least, wet-cured bacon) contains a number of additives. You already know about the artificial nitrites, of course, but all wet-cured bacon must also contain either ascorbate or sodium erythorbate; chemicals which accelerate the reaction between the nitrites and the meat, reducing the formation of nitrosamines.

Nitrosamines are essentially carcinogenic compounds that appear when you combine nitrites and naturally broken-down proteins (known as "amines") — and although they only usually appear in small amounts, the fewer your bacon contains, the better. According to the Department of Agriculture, variables that might influence the levels of nitrosamines in your bacon include the amount of nitrite added during processing, ingredients used in processing, storage conditions, cooking methods, and more. Although ascorbate and sodium erythorbate might look like nasty chemicals, they play an important part in reducing the harmful effects of nitrites.

Wet-curing bacon also involves adding sugar and salt. The salt in the curing process prevents bacterial growth by reducing the moisture that bacteria needs to grow, while sugar is often added to reduce the harsh flavor of the salt.

Is bacon bad for you?

So, here's a question: is bacon bad for you? Well, yes — and no.

According to Healthline, bacon contains 50 percent monounsaturated fat (mostly oleic acid), 40 percent saturated fat, 10 percent polyunsaturated fat and a "decent amount" of cholesterol. Most of this isn't too much of a problem, and oleic acid is actually considered a "heart-healthy" substance. Unfortunately, saturated fat is more harmful, and might increase risk factors for heart disease. This isn't a certainty, however, and the small serving size of bacon means that — as long as you live an otherwise healthy lifestyle — the saturated fat it contains probably isn't going to cause you much trouble.

Bacon also contains a number of healthy nutrients. A typical 3.5 ounce portion, for example, contains 37 grams of protein, vitamins B1, B2, B3, B5, B6 and B12, as well as iron, magnesium, zinc and potassium. It's worth noting, however, that these nutrients are also present in other, less processed meats and pork products.

Finally, there's salt. Because salt is used in both dry-curing and wet-curing, all bacon is high in salt content. Consume too much salt, and you put yourself at risk of stomach cancer, high blood pressure, and potentially heart disease — especially if you are salt-sensitive.

Bacon is made using different parts of the pig

It's not just the type of curing that affects how bacon turns out, however. In fact, there are lots of different types of bacon, which vary depending on the cut of meat used and the way it's presented. The U.S. Department of Agriculture defines bacon as "the cured belly of a swine carcass," but in the U.K. bacon is traditionally made using the back of the pig, otherwise known as the loin. This kind is fairly hard to find stateside, but is usually labelled as "back bacon."

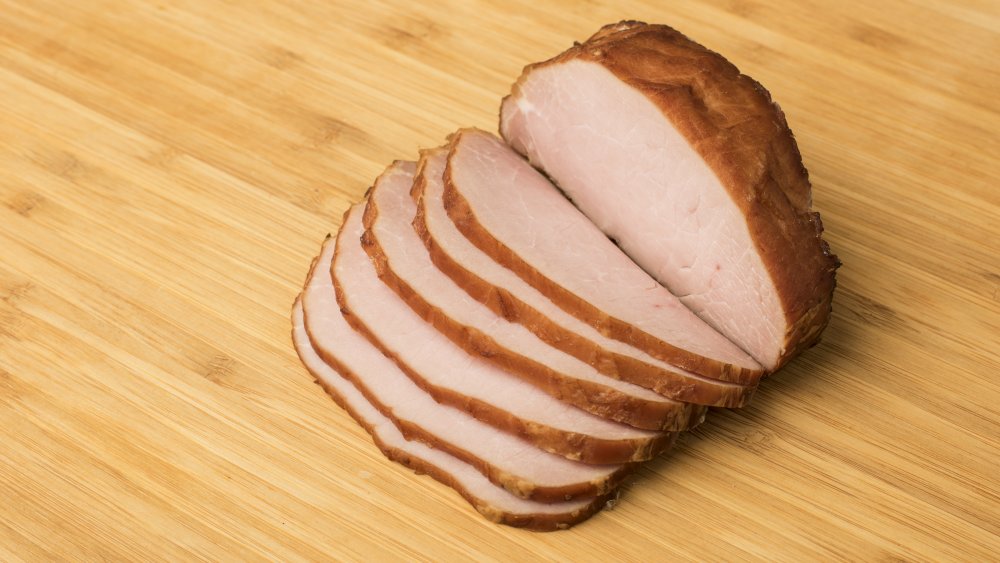

Your standard U.S. bacon is instantly recognizable: it's pork belly with veins of pink meat and white fat, cut crosswise into long, narrow slices. You've also got pancetta, an Italian version of streaky bacon. Again made from pork belly, this variant is rolled up and sliced into thin circles. Then there's Canadian bacon, which, like British bacon, is made from pork loin. This type of bacon is precooked and smoked, and usually looks and tastes a little like ham.

Slab bacon is a single piece of bacon with the rind left on, while fatback is a slab of fat cut from the loin and used as lard or cut into stripes to be wrapped around lean roasts. In Hungary and Germany, you can also get what's known as Gypsy bacon, a slab of roasted bacon, seasoned with paprika and cut into slices.

Not all "bacon" comes from pigs

Although the Department of Agriculture might be something of a stickler for defining bacon as pork belly, some companies are willing to be a little bit more liberal with the term. As a result, you can find a whole bunch of non-pork bacon alternatives out there.

Take Schmacon, for example. Despite looking very similar to real bacon, this variant is actually made from beef. You can also get D'Artagnan Uncured, a kind of smoked duck bacon — cured in celery powder, just like "uncured bacon" — that Extra Crispy describe as featuring "a little salt and some lovely fat at first, a nice toothsome quality to the meat, and then a big honking hit of duck flavor on the back end."

Turkey bacon is a little more common, of course, while smoked salmon bacon (as you might find at Trader Joe's) is just a little more off-the-wall. In their taste test, Extra Crispy describe Trader Joe's salmon bacon as "surprisingly meaty," with "a pleasant hint of smoke, along with that unmistakable salmon flavor." Smoked dulse, meanwhile, is billed as "the bacon of the sea" made from a wild sea vegetable similar, in many ways, to kelp. Of course, weird seaweed isn't the only option for veggie bacon fans. Thank God.

Not all pigs make bacon

Traditionally, pigs have been classified one of two ways: lard pigs or bacon pigs. You can probably guess which is more relevant, here.

Obviously, lard breeds were used to produce lard, and tended to be thicker and shorter than other pigs. They could be fattened quickly with a good corn diet, which was seen as a hugely desirable quality for pigs — especially if you're after a better quality cut of pork. Meanwhile, bacon pigs were lean and muscular, being fed on a diet of legumes, grains, turnips and dairy byproducts. Loaded up on proteins, these pigs would grow more muscle than other breeds, making them perfect for the production of bacon.

Before World War II, the only non-lard breeds of pig were the Yorkshire and Tamworth pigs. Today, however, bacon pigs are far more widespread — in fact, only three traditional lard pig breeds remain: the Choctaw, the Guinea Hog, and the Mulefoot. The most popular bacon breeds, meanwhile, are the Duroc, Hampshire, and Yorkshire breeds, the three of which pretty much support the entire pork industry. Most other breeds have dwindled in population, with some — such as the Mulefoot — teetering on the edge of extinction.

Some bacon is made from free-range pigs

As is the case with many animals that are farmed for consumption, some pigs live hard lives before being slaughtered for their meat. At some pig farms, pigs are reared for breeding, which means they are lined up in gestation crates and live through several cycles of pregnancy until, eventually, they are slaughtered. The piglets born from these pigs are sometimes confined in concrete pens and fattened until they reach market weight. They are then taken to be slaughtered.

Of course, this isn't how it works for all pig farms — there is a way to make sure your bacon comes from a happier place.

Pastured pigs live far better lives. These pigs are allowed to live in an open, free environment, and can graze or forage for food to their hearts' content. And it's not just the pigs who end up happier with pastured farming — you reap the benefits, too. These pigs are far less likely to contain the antibiotics and hormones that intensively-raised pigs are fed, and are raised in healthier, more hygienic conditions.

Just be careful with bacon that comes from "free range" pigs, because this can often mean only the minimum steps have been taken to meet that definition. A pig raised in a packed barn with a door at one end is not a happy pig, but you may have to ask some questions to figure out what you're getting.

Vegans can make bacon, too

So how do you make veggie (or vegan) bacon? Well, the good news is, it's easy — and you can do it with pretty much anything. The method is simple: first, choose your primary ingredient. Oh My Veggies suggest choosing a sufficiently porous ingredient as your base, with mushrooms, tofu, tempeh, chickpeas, coconut, carrots, and eggplant all being suitable options.

Next, you make a marinade. For the smokey aspects of your bacon flavor, you want to use liquid smoke or smoked paprika (or both). Salty and savory flavors can be added with soy sauce, tamari, or liquid amino. Sour notes will come courtesy of vinegar, preferably apple cider or white. And finally, sweeter elements of the flavor can be brought in with maple syrup, agave, sugar, or brown sugar. For the best marinade, you'll want to combine all of these; Oh My Veggies suggests one part smoke, three parts sweet, four parts sour, and four parts savory and salty.

Next, you marinate your base ingredient — preferably for up to 12 hours, in the refrigerator. The longer you soak, the more intense the flavor will be. Finally, you cook your "bacon," preferably in the style suitable to your base. Bake tofu, pan-fry eggplant or tempeh, or grill your mushrooms or carrots. Et voilà: tasty "bacon" with all of the flavor and none of the dead pig. What's not to like?