The Untold Truth Of Mochi Ice Cream

Mochi ice cream is one of the hottest foods to hit the market in recent years. After its quiet invention in the mid '90s, the dessert skyrocketed to prominence in the 2010s, and is now available at most major grocery chains in America.

But what exactly is mochi ice cream? Well, as the name implies, it is a variation of traditional Japanese mochi which is then stuffed with American-style ice cream. Although most Americans probably think of any mochi as having a sweet filling, traditionally, it is simply a ball of pounded glutinous rice. It can be topped with sweet things like kinako (roasted soybean powder) and black sugar syrup, dipped in something savory like soy sauce, or even served in soups like ozoni. Mochi ice cream builds on the tradition of classic mochi by using sticky, chewy skin made of glutinous rice to encase a ball of ice cream. The result is a delicious, multi-textured dessert that perfectly fuses Eastern and Western culinary traditions.

Despite being invented somewhat recently, these cute little desserts have a surprising amount of history to them. From the ancient ancestors of mochi ice cream to its most modern iterations, read on to learn about the tasty history of mochi ice cream .

Mochi ice cream's predecessors

Before there was mochi ice cream, there was, well, regular mochi. Although it is unclear when exactly mochi was invented, the technique of pounding rice into a chewy treat supposedly dates back to Japan's Yayoi Period (300 B.C.- A.D. 300). Mochi slowly proliferated over the next millennium, and was very popular by the Heian Period (794 – 1185). By 1000, mochi had become a common sweet for New Year's celebrations and began appearing in dictionaries (spelled "mochii").

Additionally, mochi is only one of several treats which resembles modern mochi ice cream. Perhaps mochi's closest relative is daifuku, a paste-filled dessert with a thin, chewy skin around it — it's essentially a filled mochi. Daifuku skin differs slightly from mochi in that it is traditionally made from shiratamako (glutinous rice powder) mixed with water and sugar, while mochi is just steamed and pounded glutinous rice. The texture of the two is remarkably similar despite their differences in composition, both delivering a wonderfully chewy bite. Manju is another similar treat which features a smooth, chewy skin and sweet filling. However, manju's skin is made from wheat, rice, and buckwheat flours, giving it a denser, cakier texture.

Daifuku, manju, and mochi are all part of the tradition of wagashi, or Japanese confectionary, which has existed for over 2,000 years. Mochi Ice cream is simply the latest innovation in this practice, and combines the best qualities of desserts already known and loved throughout Japan and the Japanese diaspora.

Lotte's yukimi daifuku — the first 'ice cream' 'mochi'

While Frances Hashimoto and her husband Joel Friedman are credited with the invention of mochi ice cream (more on that later), they were not the first to attempt stuffing frozen cream into a glutinous rice sweet. In fact, a Korean-Japanese multinational conglomerate called Lotte beat them to the punch a decade earlier, developing their own ice cream treat in the 1980s. Lotte's Yukimi Daifuku consists of a frozen cream filling wrapped in a thin daifuku skin, which is then dipped in coconut milk. Yukimi Daifuku is still on the market today in several varieties, like vanilla, roasted soy bean, and sweet potato. It remains a popular treat in Japan (via Matcha), but if you want to try it stateside, try Costco or your local Asian market.

The development of Yukimi Daifuku turned out to be a bit of a struggle — freezing something chewy and stretchy without drastically changing its texture is no easy feat. To get around their issues, Lotte's ice cream is actually "ice milk," and their skin is made with rice starch instead of pounded sticky rice (hence the name daifuku). Even though the components sound a little off, the result is a perfectly textured skin that stays soft (but not sticky!) at any temperature, plus a delectably creamy center.

Mikawaya and the popularization of mochi ice cream

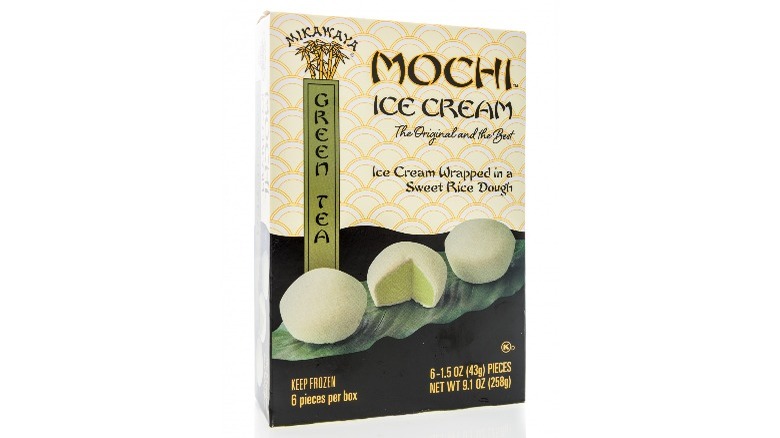

While mochi and its first "ice cream" iteration were created in Japan, mochi ice cream as we know it today originated in the United States. It was dreamed up by a couple in Los Angeles, Frances Hashimoto and Joel Friedman, who ran a 100-year-old Japanese bakery called Mikawaya. Using his American palate and Hashimoto's Japanese confectionary skills, the pair came up with an idea to adapt mochi for American markets: filling it with ice cream!

It all started with a trip to Japan, where Friedman first tried filled mochi. While he liked the concept of a sticky rice ball with a tasty filling, the texture of the traditional bean mixture didn't sit well with him (via KPCC). Friedman later revealed to CNN that the dessert really "stuck" with him, and after a discussion with his wife they decided to try and swap out the red bean filling for ice cream. Thus a million dollar idea was born. The couple's invention would put Mikawaya on the map, expanding the business from a beloved mom-and-pop staple to the center of the latest food craze.

It took 10 years to get the formula right

After initially dreaming up the idea in the mid '80s, the execution of mochi ice cream proved to be difficult. Hashimoto and Friedman hit many of the same obstacles Lotte had in the creation of Yukimi Daifuku, where the mochi skin would either freeze and become too hard or become a "sodden mess" when thawed. This is because the ice cream has to be kept cold, while the mochi skin, which is hot when it is ready, needs to be cooled down enough to encase its filling without drastically changing its texture. Apparently, their consultants in the process warned that they were attempting to "defy the very laws of physics," as if they were "mixing water and oil" (via Sushi and Tofu).

While it became clear that the process would not be an easy one, Friedman was committed to his vision. After nearly 10 years of research, Friedman realized he "had to formulate an ice cream specific to mochi" rather than trying to change the mochi dough. He was finally able to fuse the two into a singular dessert by closing the gap between the optimum temperatures of the two treats. Finally, in 1994, mochi ice cream was ready for the market.

It originally came in just three flavors

After creating the perfect formula, Mikawaya began producing their mochi ice cream in three flavors: mango, red bean, and green tea. Mochi ice cream was envisioned as fusion treat, and these three flavors were purposefully chosen to reflect the Eastern end of the bargain. However, such a purposeful blending of cultures came with a dilemma: Who will latch on to this product?

To solve the target audience problem, the research and development team looked to Hawaii, where the state's large Asian-American population would be a good middle-ground representative of both cultures. This was evidently the perfect choice. Mikawaya's mochi ice cream represented 15% of Hawaii's total ice cream sales after only 90 days. The couple were happily surprised, with Friedman telling Sushi and Tofu, "The market took all the mathematical calculations and threw them out of the window."

Friedman and Hashimoto had seen limited success when selling to local vendors or out of their storefront, but their sudden success in Hawaii attracted quite the buzz. They soon bought new mochi making machines, scaled up production, and began selling to upscale grocery chain Bristol Farms in Pasadena, California. They also debuted four new, more classically American, flavors — strawberry, chocolate, coffee, and vanilla — in preparation for their expansion into the U.S. mainland.

It blew up in the 2010s

After a stellar beginning, Mikawaya was soon fielding offers from major American retailers. By the start of the new millennium, the company was a selling more than they ever had, distributing over a million boxes within the first six months of 2001. Eventually they start selling to stores like Kroger, Gelson's, 99 Ranch, and Trader Joe's, raking in "tens of millions" of dollars in the process. Mikawaya even moved their ice cream operations from the bakery to a 103,000-square-foot factory in Vernon, California to accommodate the demand.

Unfortunately, Frances Hashimoto passed away in 2012, leaving her husband to run the bakery and rapidly expanding ice cream company by himself. Friedman consequentially sold the business to Century Park Capital Partners in 2015, who were better equipped to handle such a large company. From there, Century Park changed the name from Mikawaya to My/Mo, which rebranded to My/Mochi in 2021. (They continue to sell Mikawaya-branded mochi ice cream as well.) While the original bakery location lived on through another sale, this time to Lakeview Capital, Inc. in 2020, it closed its doors in 2021 due to "pandemic-related challenges" (via Rafu Shimpo).

Despite the unfortunate loss of Mikawya and it's fourth-generation owner, the family's baking legacy continues though My/Mochi, who dominates the mochi ice cream market. According to Refrigerated & Frozen Foods, My/Mochi currently represents 80% of mochi ice cream sales in groceries, as well as 98% of sales in convenience stores.

New flavors and sellers helped its popularity

Hesitancy in American consumers led My/Mochi to seriously rethink their flavor offerings upon their initial expansion. My/Mochi's chief marketing officer Russell Barnett explained to Vice, "consumers can deal with one change [at a time], and the one change here is dough on ice cream." So, in order to "reduce barriers," My/Mochi's flavor selection more closely resembles that of a Baskin Robins than a wagashi counter. Although they retained originals like green tea and sweet mango, American classics like cookie dough, mint chocolate chip, and chocolate sundae now feature prominently in the lineup.

In 2021, they announced the addition of coconut, guava, and horchata flavors, much to the delight of Latinx customers. They even released four vegan flavors — vanilla, chocolate, strawberry, and salted caramel — in late 2017, as well as a vegan Neapolitan soon after. Releasing flavors that appeal to a variety of different groups has helped My/Mochi retain their dominance as the top-selling mochi ice cream on the market.

It brings 'something different' to frozen goods

Marketing specialists attribute mochi ice cream's smash success on a number of factors. For one, the frozen dessert takes ice cream, whose sales have been declining, in a much needed new direction. One industry analyst told CNN that My/Mochi's unique idea brings "something different" to the ice cream world, which has otherwise seen little change in recent years.

Others, like My/Mochi's chief marketing officer Russel Barnett, attribute its success to new consumer groups. According to Barnett, Millennials are "a snacking generation," making a pre-portioned snack like a mochi pouch their ideal choice for a frozen treat. He also claims the "sensory explosion of color, texture, and taste" provided by My/Mochi is well suited to Millennial's and Gen Z's desire for novelty in the foods they eat.

The My/Mochi brand specifically is such a success because of its willingness to innovate and push for that "something different." In the past several years, My/Mochi has released several multi-layered flavors of mochi, which feature a gooey or creamy filling inside of the ice cream filling. Additionally, they launched a line of pints that have mochi bits mixed throughout, helping to ease skeptical American consumers into the trend without having them go full-out pouch mode.

Don't get it confused

While the sudden popularity of mochi ice cream has been great for Japanese bakeries stateside, it has also contributed to a lot of confusion surrounding the nation's confectionary. As you will recall, mochi in the traditional sense is not what Americans think of today, which can result in some serious misunderstandings at your local wagashi counter. If you are thinking of visiting a bakery to expand your palette, remember that most mochi does not contain ice cream, so don't be disappointed when it isn't the frozen treat you are used to.

In reality, there are dozens of types of mochi, each one tasty and unique in its own way. One popular favorite is the classic ichigo daifuku, which contains red bean paste and a whole strawberry — it makes for a great visual when cut in half. Yomogi mochi, sometimes called kusa mochi or "grass mochi," is another popular choice. This beautiful green sweet is flavored with mugwort, giving it an earthy taste. Many mochi are also seasonal, such as kinako mochi, which is mochi rolled in roasted soy bean powder and sugar, a treat that is eaten during the New Year. During the cherry blossom season, look for sakuramochi, a pink sweet filled with red bean paste and wrapped in a salty leaf from a cherry blossom tree. If you find yourself stunned by the sheer array of options, ask for an assortment of bestsellers — you won't be disappointed!

The best mochi ice creams

If you want to get a piece of the mochi ice cream action, you've also got plenty of options. Of course, Mikawaya is a classic that should not be skipped. This original mochi ice cream brand is renowned for its place in history, as well as its commitment to top-of-the-line, natural flavorings. A favorite in Hawaii, Bubbies mochi ice cream are sweet, creamy, and the perfect texture. They're also a great starting point for the hesitant snacker, as they are sold individually in Whole Foods' "mochi bar" cases.

Mt. Fuji is a great option for the traditionalists out there. This brand is more suited to an Asian palate, so their focus is on delectable flavor rather than sticky sweetness. And as a green tea producer, Maeda-En makes a stellar green tea mochi using their high-quality teas. In addition to these brands, which are widely available, check out local Asian bakeries and groceries for the best hidden gems.