The Truth About Fortune Cookies

For almost a century now, diners across the United States have been greeted by the same thing at the end of a meal at a Chinese restaurant — a fortune cookie. These delightful little treats offer just enough sweetness crossing the palate to satiate even the most sugar-hungry diners. Before you get to the eating of the cookie though, you have to attend to the most important part (it is in the name, after all) — the fortune, accompanied by a string of lucky numbers. On the back, too, there is sometimes a Chinese language lesson. Whether you believe in the fortunes or the lucky numbers is irrelevant, as fortune cookies are an integral part of an American Chinese meal that will likely not go away any time soon ... if ever.

As omnipresent as they are, though, do you know anything about them? Since they're offered at Chinese restaurants, are they Chinese in origin? Has history recorded the name of the inventor? If they're in just about every Chinese restaurant in America, how many cookies are made every year? Read on to dig in to the scrumptious — and surprising — history of the fortune cookie.

Fortune cookies are not Chinese in origin, but Japanese

Let's get the most pressing point out of the way first — the historical roots of fortune cookies are not Chinese at all. Instead, research points to Japan as the source of what would become fortune cookies as they are known today.

According to researcher Yasuko Nakamachi — who was interviewed by Jennifer 8. Lee, author of The Fortune CookieChronicles – fortune cookies can trace their origins to bakeries outside of Kyoto, Japan. Nakamachi's proof lies in family bakeries that surround Kyoto and the fact that they made fortune cookie-shaped crackers. Further, there is visual evidence (an image from the 1870s) that shows a baker making them in his bakery.

Nakamachi first saw fortune cookies while in a Chinese restaurant in New York City, but after seeing someone making them at a bakery in Japan — complete with a piece of paper tucked inside — it set her off on a quest to find the fortune cookie's true origins. The main differences between Japanese and American fortune cookies, she found, were in the size, the flavoring, and the position of the fortune. These Japanese cookies were bigger, used sesame and miso (not vanilla and butter), and had the fortunes pinched in the mouth (not folded inside).

The message inside the cookie is said to go back as far as the 14th century

While the idea of a fortune cookie is not Chinese in origin, when it comes to the actual fortune part of the fortune cookie, there is some evidence that suggests that it did indeed come from China. Sources point to the mid-autumn moon festival, which is celebrated on the 15th day of the eighth month on the Chinese calendar. On this day, mooncakes were distributed widely.

The cakes, which were made with a lotus nut paste, were avoided by the Mongol overlords because they didn't like the taste. The Chinese used this to their advantage, hiding instructions for rebellion inside the mooncakes and sending priests inside the occupied city's walls to distribute them. Once the instructions were distributed, the rebels were able to surprise the Mongols and overthrow them. This well-thought out plan and hard-fought victory led to the establishment of the storied Ming Dynasty, which ruled from 1368 all the way until 1644 C.E., when the Qing Dynasty took over following the last Ming Emperor Chóngzhēn's suicide (via History).

Fortune cookies were invented in California

While the cookie's historic roots can be traced to Japan, and the idea of the fortune inside a cookie can be traced even further back to 1300s China, the fortune cookie known today is believed to have been invented in 1900s California. Japanese immigration to the United States was a slow and steady process, with communities slowly popping up in various places (such as Japan Town in San Francisco) along the West Coast. As the 1900s began, more and more Japanese people started moving stateside, taking jobs first on farms or other places of hard labor. Some eventually were able to open their own businesses, and more, leading to even more population growth. It is within this context that fortune cookies were invented.

There are two sites that claim ownership over the founding city of the fortune cookie. On one hand, you have San Francisco, and on the other, you have Los Angeles (via American Heritage). Both cities had growing (and engaged) Japanese populations in the early 1900s, with plenty of places — bakeries, for example — where the cookies may have originated.

There are two people who possibly invented the fortune cookie

Like many famous foods/objects/really anything throughout history, the actual inventor of the fortune cookie is a hotly contested subject. There are two main contenders for the title of fortune cookie inventor. First, there is Makoto Hagiwara. Hagiwara was a Japanese immigrant who was (as of 1895) employed as the caretaker for San Francisco's Japanese Tea Gardens. Then, sometime between 1907 and 1909, Hagiwara began serving cookies based on Japanese senbei (toasted rice wafers) to visitors of the garden. Allegedly, the cookies contained thank you notes which acknowledged the public for having him re-hired at the gardens after Mayor James Phelan — who was a known racist and hated people of Asian descent — fired him.

The second contender is David Jung, a Los Angeleno who founded the Hong Kong Noodle Company in 1916. Originally from Canton, China, Jung had claimed that he invented the fortune cookie around 1918 when he would give cookies to out-of-work people that contained scripture messages of hope and persistence. The thing about this claim, though, is that there is no physical evidence left to prove that Jung did invent the cookie.

A court hearing decided who actually invented the fortune cookie

In an effort to put the Los Angeles–San Francisco rivalry to rest and state for the record who actually invented the fortune cookie, the Court of Historical Review – a San Francisco-based organization — held a trial in 1983. Shockingly — or perhaps not, if you consider where the Court of Historical Review is based – it was decided that Makoto Hagiwara was the inventor and the city of San Francisco the home of the fortune cookie. During the trial, the man overseeing the case (a real federal judge named Daniel M. Hanlon), was allegedly given a fortune cookie that read, "S.F. Judge who rules for L.A. not very smart cookie."

It is one thing to hold a "trial" to decide an answer to something like the founding of a food, but no matter how you look at it, the trial was a product of the time. Participants in the trial not only donned clothing designed to look like ancient Chinese robes, but they also spoke in a pidgin English while recounting each claimant's history of the cookie. (Other evidence was issued as well, such as a set of grills that were used to create the cookies.) To this day, San Franciscans and Angelenos still don't agree on who actually invented the fortune cookie.

Fortune cookie production transitioned from Japanese bakers to Chinese bakers during WWII

Fortune cookies as a staple in American Chinese restaurants really took hold in and around World War II. This transition from Japanese-American to Chinese-American prominence, though, is not because of a happy, seamless, peaceful shift.

During World War II, Japanese-Americans were put in internment camps in the United States (this was a response by President Franklin Roosevelt and the U.S. government to the attack on Pearl Harbor). Without Japanese-Americans producing fortune cookies, it was during this time that enterprising Chinese businessmen decided to start making cookies of their own and selling them to Chinese restaurants. This started the proliferation of fortune cookies that has maintained a steady increase through the present day.

When soldiers came home from war — and even more so as American families began to dine out in the 1950s and beyond — the wish for something sweet after dinner was great. And since Chinese cuisine did not have many sweet dessert options (compared to, say, French or Italian cuisines), restaurateurs offered up Fortune cookies, which were promptly cracked open and gobbled up.

The fortune cookie-making process was automated in the 1960s

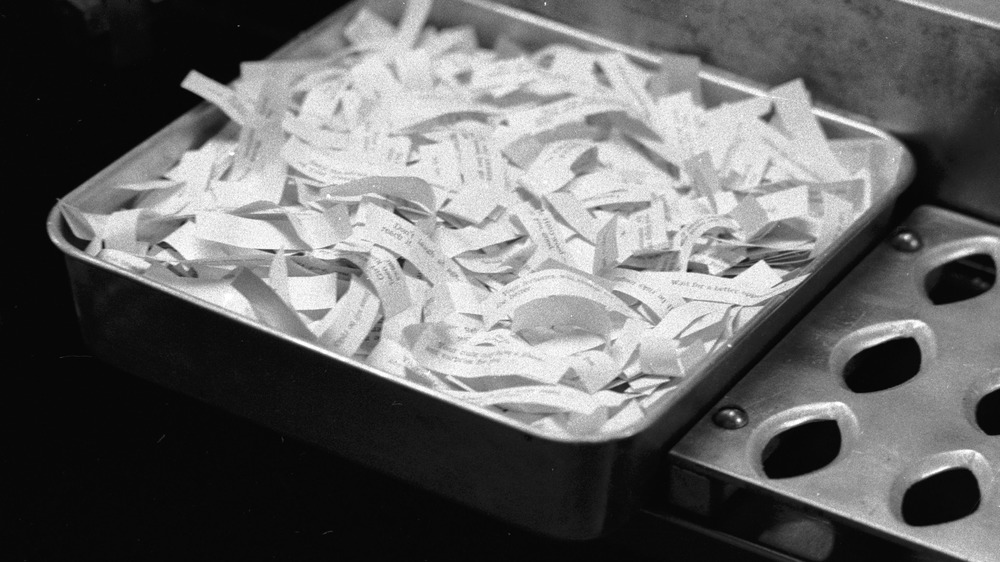

From the time of their invention in the early 1900s through the middle of the century, fortune cookies were made by hand. Once mixed, fortune cookie dough would be poured onto a tray, heated, and shaped as the fortunes were put inside. While it only takes about a minute to cook fortune cookies, this time really adds up when you're doing the entire process by hand.

This process was kept up until one enterprising man by the name of Edward Louie. Louie, who opened San Francisco's Lotus Fortune Cookie Company in 1946, decided he needed to find a way to save his family the trouble of individually wrapping hundreds if not thousands of fortunes cookies every day. He set to work and in the 1960s invented a machine that automated the process by inserting the fortune cookie and folding it together. This machine allowed Lotus to create up to 90,000 fortune cookies per day, further boosting the ability to find fortune cookies far and wide.

Three billion fortune cookies are produced every year

The world of fortune cookie production has come a long way since the early 1900s when they were made by hand. Even with the advent of fortune cookie automation — which boosted production to 90,000 cookies per day — it is nothing compared to the number of cookies being produced currently. In total, around 3 billion fortune cookies are produced per year. That's an average of around nine cookies per person in the United States per year.

Now, these are not only intended for Chinese restaurants. In fact, fortune cookies have been used as a promotional device for a variety of things for years. The movie Kung Fu Panda 3, for example, created a slew of fortune cookies with quotations from the movie's protagonist Po (voiced by Jack Black). Before Kung Fu Panda, other movies such as Billy Wilder's 1966 comedy The Fortune Cookie (starring Walter Matthau and Jack Lemon in their first on-screen collaboration) also used fortune cookies as promotional items.

Wonton Food Incorporated is the largest producer of fortune cookies in the world

In the wide world of fortune cookies, there is one cookie company to rule them all, so to speak. While there are a number of companies who produce fortune cookies (there are larger manufacturers such as Los Angeles's Peking and Baily International Food of Illinois as well as many smaller businesses), Wonton Food Incorporated sits atop the fortune cookie heap. A family-owned company that was started in 1973 by Ching Sun Wong (who immigrated from Guangdong, China in the 1960s), Wonton Food has established itself as the worldwide leader in fortune cookie production, churning out over 4.5 million cookies per day. Wonton Food currently produces four flavors of fortune cookie — vanilla, citrus, chocolate, and tri-flavor, a mixture of the previous three.

In addition to their fortune cookie mastery, Wonton Food also is a leader in other Chinese foodstuffs, producing a variety of dry and crispy noodles, wrappers for different types of rolls, soy and mung bean sprouts, and more.

Fortune cookies aren't eaten in China

This may or may not come as a surprise, but much of what you may consider Chinese food in the United States is not actually consumed in China. A slew of dishes that grace just about every Chinese food menu in the states — which the dishes may be able to sort of trace roots to authentic Chinese cuisine — were actually invented in the states to appease the American palate at the time of invention. Chop Suey is a prime example of this. Said to be created during the California Gold Rush for intoxicated miners, the dish became synonymous with "Chinese cuisine" for a very long time. (It is safe to say that General Tso's chicken, which was created in New York City in the 1970s, has since taken that mantle.)

Fortune cookies are no different. These sweet treats, which were invented in California, hardly if ever show up at the end of a meal in China. Wonton Food Inc, the largest producer of fortune cookies in the world, attempted to expand business to China in the 1990s, but the effort did not produce results. Instead of fortune cookies, dinner in China is more likely to finish with orange slices.

Fortune cookies are made of four basic ingredients

Part of the beauty of the fortune cookie is in its simplicity — open the wrapper, break the cookie open, find your fortune, eat the cookie. Four things create the ritual that has not changed much since its inception a century ago. Another thing that is simple about the fortune cookie? The recipe. In its essence, fortune cookies contain four basic ingredients – flour, sugar, water, and eggs. With these, fortune cookies can be made. These, of course, are the basis for many baked goods, but if they're all you've got, you're on your way.

If you are making them at home, you might be adding a few other ingredients as well. A flavoring agent, such as vanilla or almond extract, is a popular addition, as are butter and a little bit of salt. On the commercial level, though, more ingredients are added so that the cookies will not spoil on their journey to Chinese restaurants nationwide. These ingredients include anticaking agents, stabilizing agents, baking powder, and baking soda — no one wants to find a gummed-up or broken fortune cookie in the bottom of their to-go bag.

For much of Wonton Food's existence, the company has had only one fortune writer

Even though it produces the most fortune cookies in the world, Wonton Food — for more than 30 years — only employed one fortune writer. That man, Donald Lau, was chosen because of his command of the English language (Lau now also serves as the chief financial officer and vice president) and continued to write multiple fortunes a day for 30 years.

When Lau took over writing fortunes in the 1980s, the company had only a couple hundred to choose from. Lau rewrote and refreshed the ones they had and continued to add more. Now, Wonton Food's fortune library numbers over 10,000. What started out very similar to the current fortunes evolved, and Lau began using dry wit and everyday observances to craft fortunes. These he would test on friends and coworkers and if they passed, the fortunes would likely make it into a cookie. In 2017, he retired from fortune writing and passed the duties on to Wonton Food Assistant Vice President James Wong, the nephew of the founder of Wonton Food.

The numbers on fortunes may actually be lucky

Okay, so considering your fortune may sometimes read "you will find the love of your life" or some other such platitude, it might be hard to believe that the numbers contained on fortunes are lucky, but research says that they actually might be. In 2017, statistics website FiveThirtyEight bought 1,035 Panda-brand cookies in order to analyze the lucky numbers held within. There were 676 unique fortunes in the lot and 556 combinations of lucky numbers. Then, they analyzed the Powerball numbers for every drawing between Nov. 1, 1997 and May 27, 2017. The results were surprising. If a person bought a ticket every day during that time, they would've spent $4.2 million. Then, if they used every possible combination, they would've netted a grand total of around $4.4 million dollars. If they had used random numbers in that time, they would've only won $1.7 million (while still spending $4.2 million).

In fact, there was even a brief investigation into Wonton Food when, on March 30, 2005, over 100 people from 29 states got five of six numbers right, netting the group over $19 million dollars total.