What Alternative Sweetener Should You Really Be Using?

We all know we should try to cut down on added sugar, the dietary culprit that is apparently making us fat, rotting our teeth, taxing our liver, and causing cancer and type 2 diabetes. But what to do when you just gotta satisfy that sweet tooth? Well, you have choices — probably far more than you realize!

Artificial sweeteners began flooding the marketplace as far back as 1879, and there is a lot that makes them an attractive choice — low or zero calorie counts, low cost, as well as barely perceptible effects on blood sugar levels. But consumers are concerned about the healthiness of these chemical concoctions, with many people believing artificial sweeteners are linked to an array of diseases and disorders. Luckily, there are also plenty of natural sugar alternatives available to us, and figuring out the right one for you is about personal preference, and determining how well your own body may react to your sweetener of choice.

So, what artificial sweetener should you really be using? Quite simply, the one you feel most comfortable with after being armed with all the information about what's in these sweeteners, how some of them came to be, and what the science really says about how healthy they are for us.

Sucralose

Around 600 times sweeter than sucrose, and one of the world's top artificial sweeteners, sucralose is sold under the brand name Splenda, which exploded on the marketplace in 1998, after a lab tech inadvertently tasted a chlorinated sugar compound he was working on. Sucralose was initially praised for it's creation stemming from actual real sugar, using a process that selectively chlorinates sucrose. Consumers and manufacturers alike also embraced sucralose for its ability to stand up to high-heat baking, while top competitor aspartame loses its potency. Sucralose can be found in a myriad of products, from power bars, to drink mixes, to salad dressings...even children's vitamins.

But it's hard to be an artificial sweetener without being mired with controversy. The FDA itself reported in 1998 that tests indicated sucralose caused minor genetic damage in mouse cells, and also produced a substance in the human body that was "mildly mutagenic in the Ames test," a test widely used to test for carcinogens. Dr. Susan Schiffman, of Duke University Medical Center and sweetener specialist, told the New York Times in 2005, "The sucralose people keep saying 'It's just a little bit of a mutagen.' Well, I don't want a little bit of a mutagen in my food supply. How do you know what happens in a long life span or to the next generation or to your eggs and sperm? I don't feel like the issues have been answered." In further years, Dr. Schiffman was instrumental in studies that have shown that sucralose, when cooked at high heat, generates chloropropanols, a potential toxin (A fact that remains absent from the FDA website). Splenda has also been shown in tests to reduce the number of beneficial bacteria in the guts of lab rats, though human studies remain to be performed.

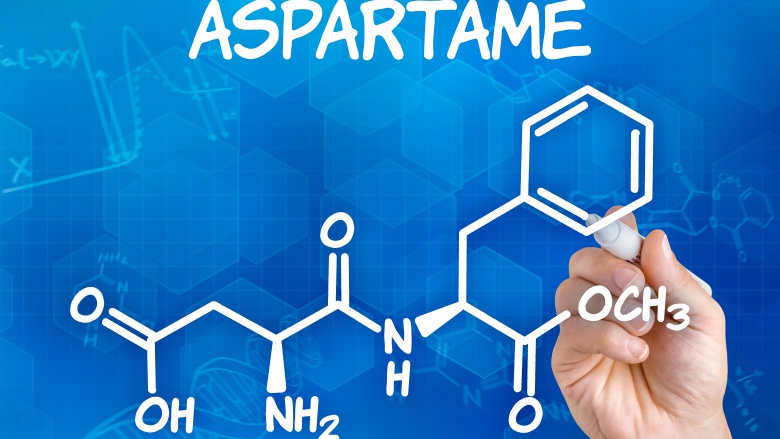

Aspartame

Although it's not good for baking (it loses its sweetness at high heats), aspartame sweetens everything from sugar-free candy to over-the-counter cough syrup, and is 200 times sweeter than sugar. Created by combining the amino acids aspartic acid and phenylalanine, aspartame was accidentally stumbled upon in the lab by a chemist working on treatments for ulcers, and is sold under the brand names Equal and NutraSweet. Though currently in good standing with the FDA, critics of the sweetener claim that regular consumption can lead to brain tumors, blindness, seizures, cancer, depression, multiple sclerosis, and Alzheimer's...to name just a few of the purported maladies. Though scientific studies have never shown conclusive data that supports these claims — in fact, aspartame is by far the most-tested artificial sweetener in existence. Still, the sweetener has started to develop an infamous reputation across the globe — even soda giant Pepsi has answered the demands of growing public concern, and replaced aspartame with less controversial sweeteners Ace K and sucralose in its Diet Pepsi products.

The FDA's approval of aspartame (a product previously owned by Monsanto) was not without its fair share of controversy, so you may want to bone up on the topic before downing your next Diet Coke. The FDA does offer one warning about aspartame's use – it should never be consumed by anyone suffering from a rare hereditary condition known as phenylketonuria, or PKU, which diminishes the body's ability to metabolize phenylalanine properly.

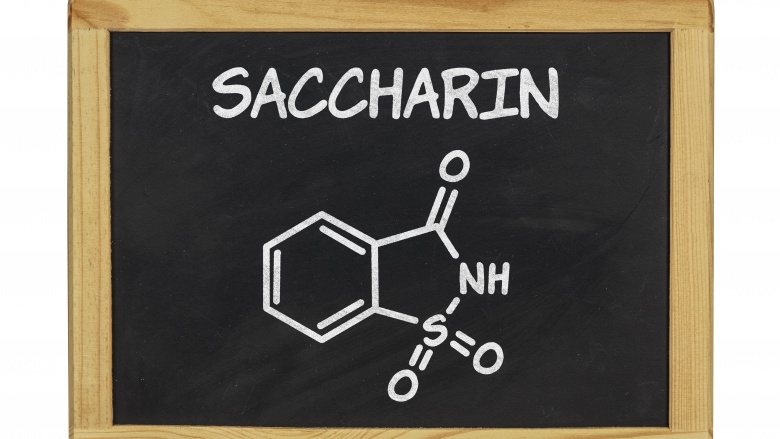

Saccharin

The granddaddy of all artificial sweeteners, saccharin was also accidentally discovered by a chemist, in 1879. The chemical quickly gained in popularity and was regarded not only as a dietetic sweetener, but also a canning preservative, and treatment for headaches and nausea. Though it met with some resistance by those who pointed to it's unnatural make up (the chemist who stumbled upon it was working on coal-tar derivatives) saccharin was beloved among dieters, even Teddy Roosevelt himself, who was instrumental in keeping the sweet concoction available to the public. Saccharin surged in adoration during World War I, with its' largest distributor, Monsanto, rallying the public to its benefits during sugar shortages. The 50s ushered in those little pink packets, Sweet'N Low, a blend of saccharin and yet another controversial sweetener, cyclamate, whose addition tempered saccharin's bitter after taste.

In 1977, scientific studies showed a correlation between saccharin consumption and cancer in lab rats. The saccharin industry, particularly Sweet'N Low manufacturer, The Cumberland Packing Corporation, who were already reeling from a previous ban on cyclamate, waged a PR war, declaring a possible ban to be the interference of big government in consumers' lives.

Though the FDA was unsuccessful in removing the compound from the marketplace, they did require products containing saccharin carry warning labels; a move that amusingly saw a huge spike in sales of Sweet'N Low, as saccharin fans, concerned over a permanent ban, rushed to the stores to stock up. Saccharin's popularity did begin to decline, however, as more artificial sweeteners were introduced to the marketplace. The FDA lifted the warning requirement on saccharin in 2000, when saccharin was removed from the list of known carcinogens.

Acesulfame potassium

You may have never heard of acesulfame potassium, but chances are likely that you have consumed it numerous times. Approved by the FDA in 1988, the sweetener, like aspartame, is 200 times sweeter than sucrose. Acesulfame potassium, also known as acesulfame K, or ace K for short, is sold under the brand names Sunnett and Sweet One, brand names you've probably only seen sporadically in a restaurant sugar caddy. Ace K is everywhere, though (particularly in diet sodas) as it's most often used in conjunction with other artificial sweeteners by manufacturers who are constantly seeking that elusive blend that delivers a non-bitter, more sucrose-like taste. According to the Calorie Control Council, who bill themselves as "an international association representing the low- and reduced-calorie food and beverage industry," "When acesulfame K is combined with other low-calorie sweeteners, they enhance each other so that the combinations are sweeter than the sum of the individual sweeteners with significantly improved taste profiles."

Like most artificial sweeteners, there was push back on Ace K's approval in the marketplace, with the Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI) citing two scientific studies that linked Ace K to tumors in animal subjects. Executive Director, Michael Jacobson, told the New York Times in 1988, ”I am shocked that the FDA would approve a chemical that indicates an increased risk of lung and mammary tumors in rat studies." Ace K marched on into the market in the United States as well as Europe (where it's called E950,) however, though current critics warn that the original animal studies proving its safety were in fact faulty.

Neotame

In 2002, the FDA approved neotame. Sold under the brand name Newtame, neotame, which is approximately 8000 times sweeter than sugar, is brought to you by the same folks who give us NutraSweet. A chemical cousin to aspartame, neotame is heat stable, and cleared as safe for those suffering from phenylketonuria, due to the far lower concentrations needed to sweeten the foods it's found in.

In fact, the amount of neotame used to sweeten foods in so incredibly low, that consumer advocates the Center for Science in the Public Interest, a group that rallies against many food additives, particularly artificial sweeteners, regard neotame as safe. That hasn't stopped holistic activists from demonizing neotame, who claim that, like aspartame, neotame is broken down into formaldehyde in the body, causing gradual, long-term health issues. An internet rumor swirled in 2010, that claimed that neotame's tiny doses were designed so that it can be snuck past the labeling of certified organic foods. The rumor was debunked by the Cornucopia Institute.

Advantame

What's sweeter than sweet? In the battle to produce the sweetest (and therefore most cost-effective) artificial sweetener on the market, Japanese food production giant, Ajinomoto, brings us advantame. At 20,000 times the sweetness of sugar, advantame was approved in the United States and Europe (were its called E969) in 2014 for use in commercial goods, though no brand name product is available currently to consumers. Advantame is yet another artificial sweetener that was developed from big brother aspartame, though, like neotame, the miniscule amounts needed of the crystalline powder make its sweetness stable when cooked at high heats. The FDA also says that those living with phenylketonuria can safely enjoy the product, as the amount of phenylalanine it delivers to the body would be negligible.

Advantame is another artificial sweetener to get the thumbs up from consumer watchdogs the Center for Science in the Public Interest. Says Doctor of Organic Chemistry Josh Bloom, of the American Council of Science and Health, "About the only way this stuff could harm you is if you were run over by a truck delivering it." Advantame is new to the artificial sweetener party, however, so it probably won't be long until holistic-minded bloggers begin pointing to its relation to aspartame as a cause for concern.

Cyclamate

Though banned by the FDA in 1970, cyclamate was once a popular artificial sweetener in the US, and is still used in food products around the world. In fact, pick up a pink packet of SweetN'Low in Canada, and you will see it is cyclamate listed as the main ingredient, not saccharin, which is banned there as a food additive. The original formula for SweetN' Low in the US was a blend of saccharin and cyclamate, but when scientific studies in the '60s indicated cyclamate was linked to bladder tumors in lab rats, the US version of the product was reformulated to be a mixture of saccharin, dextrose, and cream of tartar.

The quick ban on cyclamate likely prompted the backlash against the proposed ban on saccharin a few years later. In subsequent years, animal studies done on cyclamate have not shown any cause for concern, and the National Academy of Science says "The totality of evidence from studies in animals does not indicate that cyclamate (or its metabolite) is carcinogenic." That has not changed the FDA's stance, however, who have repeatedly denied appeals from the makers of cyclamate to list it as a safe food additive in the United States.

Sugar alcohols

If your quest to find your preferred alternative sweetener has led you to experiment with more natural choices, you have no doubt encountered sugar alcohols. No, they don't contain that kind of alcohol, so they are perfectly safe for alcoholics.

Sugar alcohols, also called polyols, are found naturally in some fruits and vegetables, though most of the ones you can buy at the store have been developed from the sugars found in corn. Unlike most artificial sweeteners, sugar alcohols do have some calories. Sugar alcohols also have a reputation for having laxative effects in some users, or other gastric discomfort — so tread lightly if this is your first foray.

Xylitol, one of the most popular sugar alcohols, has about 40 percent the calories of sugar, as well as the distinction of being largely considered a means of fighting tooth decay (though that claim may very well be on its way to being debunked). Like other sugar alcohols, xylitol can cause gastric distress for some people, particularly those new to sugar alcohols.

Erythritol, another popular sugar alcohol on the market, is derived from glucose, and valued for its sugar-like mouthfeel. Erythritol is one of the main ingredients in Truvia, along with stevia. At only 6 percent the calories of sugar, and with its stability at high heats, it's a favorite amongst many sugar alcohol fans, who also point to its low glycemic index, as well as its ability to be well-tolerated digestively by most users.

Sorbitol is a sugar alcohol you will see on the ingredients list of many low-sugar food products. It has 60 percent of the calories in sugar, and does not seem to spike blood sugar, though it can cause severe digestive issues for many people who use it.

Malitol, another sugar alcohol that you will see on many food labels, has about 50% of the calories of sugar, with the most sugar-like taste of the sugar alcohols. Malitol, however does cause a significant spike in blood sugar, so may not be an appropriate choice for those monitoring their blood sugar and insulin.

There are many more sugar alcohols on the market that don't enjoy the same popularity as xylitol, erythritol, sorbitol, and malitol, but are used regularly as sweetener blends or coatings for candies and medicines. They include: isomalt, mannitol (also used as a prescription medication,) lactitol, glycerol, and HSH (hydrogenated starch hydrolysates).

Monk fruit

Monk fruit as a sweetener may be relatively new in the marketplace, but the fruit itself, also called lo han guo, has been consumed in Asia for hundreds of years. With zero calories and at almost 200 times the sweetness of sugar, it's no wonder monk fruit is becoming a popular choice for those seeking an all-natural alternative to sugar. Monk fruit is a unique sweetener in that it has also been shown to have antioxidant properties, and studies have even indicated it may be useful in inhibiting growth in cancer cells, as well as instrumental in lowering blood sugar. Monk fruit is sold under a few different brand names like Purefruit and Monk Fruit in the Raw. The Splenda company makes one called Nectresse, but you may want to be wary of this one, as it is blended with sugar and molasses, which are certainly not no-calorie options.

Stevia

All natural, zero calories, and proven health benefits...what's not to love about stevia? Stevia is available as a powder or liquid form, and is hundreds of times sweeter than sugar. The sweet stuff is extracted from the green, leafy stevia plant, which you can also buy whole and crushed. When buying liquid stevia extract, keep an eye on the ingredients list, as stevia is often delivered as a tincture made with alcohol or glycerine, with opinions varying widely on the taste preferences of the two (so don't give up on stevia until you have tried it in different forms). Baking with stevia can be a challenge, with one cup of sugar being equal to about one teaspoon of stevia. Commercial stevia products designed for baking, like Truvia, are typically blended with another sweetener that provides the proper bulk.

Stevia has been used around the world for hundreds of years, and studies have shown it can be useful in lowering blood pressure and increasing the body's production of insulin. While early studies showed that stevia may have a deleterious effect on fertility, those studies have proven to be flawed.