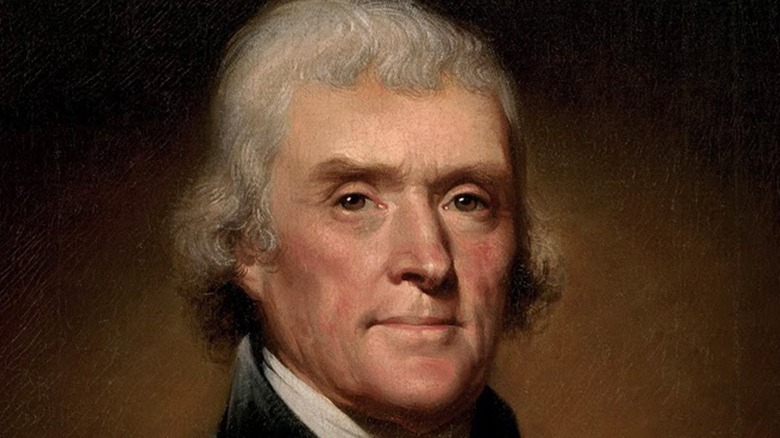

How Thomas Jefferson Helped Popularize Macaroni Pasta In The US

Thomas Jefferson may have drafted the Declaration of Independence, but another one of his written works, a recipe for macaroni, had just as much impact on American history (via Monticello). Though the recipe is not a government document, it is a product of Jefferson's efforts to popularize pasta in the U.S. Jefferson did not invent macaroni, nor was he the first to make it in the U.S., however, he was known for serving it to his dinner guests during his presidency. He had it so often enough that the recipe survives to this day.

Jefferson's love for macaroni, a term he used to describe all pasta in general, began during a trip to Naples, sometime before 1789 (via The Atlantic). Jefferson's notes from the trip are filled with detailed descriptions about the pasta-making process from the specific ingredients used to the mechanics behind the machine that was used to roll out and cut the dough. "The best maccaroni in Italy is made with a particular sort of flour called Semola, in Naples: but in almost every shop a different sort of flour is commonly used," Jefferson wrote in a journal entry shared by Monticello. He brought his appreciation of pasta all the way to the U.S. and went so far as to commission his secretary William Short to track down "a mould for making maccaroni" so that he could share it with everyone in America.

Philadelphia was home to the first American pasta factory because of Thomas Jefferson

Nowadays, when Americans want to make pasta, the kind from scratch isn't the first that comes to mind. Grocery stores are filled with shelves of commercially-produced boxed pastas with practically every shape imaginable from penne to fettuccine, and, of course, the one that came to be known as macaroni. In Jefferson's time, it wasn't that convenient, because pasta wasn't always a popular option in America. The Atlantic reported that before 1798, Jefferson had no other choice but to make his own macaroni or ship himself cases of the dried variety from abroad, which he often did.

Thanks to his influence in the political sphere, Jefferson's crowd of fellow diplomats and upper-class Americans began to import macaroni from Sicily, giving it a "snob appeal," and in 1798, the metropolitan city of Philadelphia, where Jefferson lived at the time, finally opened up its first pasta factory. It was met with enormous success. When Jefferson moved to Virginia, one of his biggest concerns, written in a series of letters shared to food distributor Gordon, Trokes & Co, was the availability of macaroni there (via National Archives).

Jefferson apparently was the biggest advocate of macaroni accessibility, and by the Civil War, enough factories opened that it became affordable for all (via The Atlantic). As it turns out, long before the wave of Italian immigration in the early 1900s, Thomas Jefferson was already busy introducing Americans to his favorite food.