The Untold Truth Of Yoo-Hoo

During those many trips to the convenience store, gas station, grocery store, or drugstore throughout our lives, you sometimes want a treat. And when one gets thirsty or just wants to reward or treat themselves for a job well done, there are many beverage options that do the trick, including soda, juice, bottled tea, flavored water ... or a Yoo-hoo. Sitting there on the shelves, basically saying "hello, look at me!" with its iconic bright yellow packaging.

And it's pretty unique once you open the bottle, too. Yoo-hoo is a chocolate-flavored, chocolate-milk-like drink that sort of tastes like hot cocoa and sort of like a candy bar. Yoo-hoo is familiar — it seems like it's been around forever, right? And although it's best served cold and crisp, all that nostalgia associated with the drink can still make a person feel all warm and fuzzy inside (not to mention a slight to considerably sugar buzz, because Yoo-hoo is some seriously sweet stuff).

But while Yoo-hoo is a stalwart of American life and is a first-ballot inductee if there were ever going to be a hall of fame for packaged foods, it remains somewhat mysterious. Here's every answer to every question you may have ever had about good old Yoo-hoo.

The birth of Yoo-hoo

Before there was mass-produced and mass-distributed chocolate-flavored Yoo-hoo, there was Tru-Fruit. That was a small, New Jersey-based beverage operation that also marketed some of its products under the name Yoo-hoo. According to Evan Morris's "From Altoids to Zima," Natale Olivieri ran the business, bottling and selling fresh fruit juice concoctions throughout the 1920s.

One day, and despite the Tru-Fruit name, he decided to make a packaged chocolate-flavored drink, but couldn't figure out how to bottle milk without the product inside going bad very quickly. The solution to his problem finally came to him after observing his wife jar up batches of homemade tomato sauce. In a step known to many home canners already, she boiled the jars before sealing them, a trick meant to sterilize the jars and preserve food for months on end. After some trial and error, Olivieri finally figured out how to bottle his carefully crafted chocolate concoction. Surprisingly enough, he found that gently shaking the bottles during the boiling process killed most bacteria.

As a chocolate beverage wouldn't make sense bearing the label "Tru-Fruit," the Olivieris took their product to market as Yoo-hoo Chocolate Drink. That phrase, "yoo hoo", was common at the time, akin to "Hello over there!" or, "Hey, look at me!" According to Sherri Liberman's "American Food by the Decades," it was the style at the time to give convenience beverages such a conversational and peppy name. For instance, similarly named drinks like Moxie and Whoopee were already popular.

Yoo-hoo isn't exactly chocolate milk

For many of us, cracking open a Yoo-hoo conjures feelings of warm, wholesome nostalgia. It's strongly associated with bygone, mid to late-20th-century American life, if not your own childhood. Both of these are likely to be times when people seemed to drink a lot of milk because that was perceived as a healthy thing to do.

Yoo-hoo, however, is not altogether all that healthy because, well, it's not altogether milk. In a general and overarching way, Yoo-hoo is chocolate-flavored milk, sure, but it's chocolate-flavored milk that's been heavily modified so as to remain shelf-stable and safely non-refrigerated for months on end.

According to Yahoo, there's no milk in its liquid form in Yoo-hoo, which is why it's technically and legally labeled as a "drink" and not "milk." Along with the primary ingredients of water and high fructose corn syrup, Yoo-hoo contains the dairy byproduct known as whey, as well as tiny amounts of dried nonfat milk and the dairy-based protein called sodium caseinate. A bunch of preservatives helps to keep the drink shelf-stable but that only works so long as everything's sealed. Once it's opened, a container of Yoo-hoo must be refrigerated, as those natural dairy ingredients do spoil quickly.

Yoo-hoo has been available in many flavors

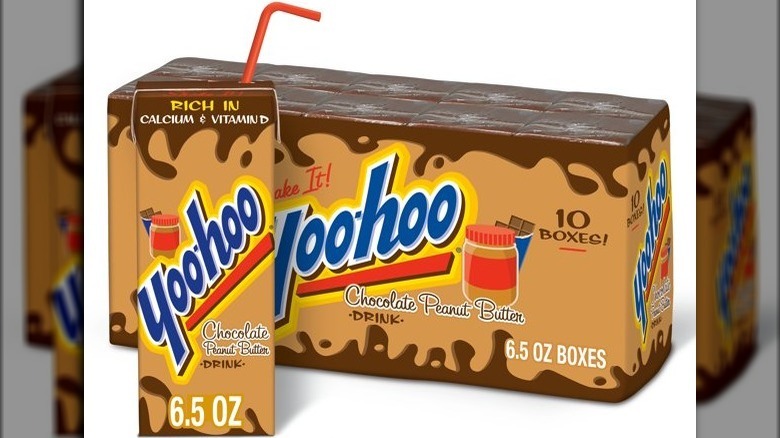

Yoo-hoo is most commonly thought of as a chocolate-flavored drink. It's likely because that was the first and most market-dominant Yoo-hoo flavor, and on account of how it mimics the flavor of chocolate milk and hot chocolate, two beverages that long predate commercial drink bottling. Yet, Yoo-hoo is actually available in a wide array of flavors, some of which sort of push the envelope in terms of what constitutes an appealing, sweetened, milk-suggesting beverage. The original, chocolate-flavored Yoo-hoo is the standard-bearer and, if a store will devote some shelf space to the product, it will certainly be in that flavor.

Yoo-hoo's bottlers produce and distribute the beverage in bottles, cans, and cardboard aseptic packaging and, key to expanding your Yoo-hoo flavor horizons, they also come in multiple flavors. Among them are Strawberry, Chocolate Strawberry, the Milky Way-esque Chocolate Caramel, and the Reese's-mimicking Chocolate Peanut Butter. As you may have already guessed, most of these side flavors are just a little bit harder to find than regular, chocolate Yoo-hoo.

While chocolate, strawberry, and the rest continue to make their way from grocery stores to customers' homes, some other Yoo-hoo flavors failed to capture the public's interest. According to Totally the Bomb, a vanilla-flavored version (marketing suggested it tasted like soft serve ice cream) hit shelves in 2019 and then disappeared in short order. The same unfortunate fate befell the Yoo-hoo flavors Cookies & Cream, Island Coconut, Double Fudge, and Chocolate Banana (via EveryThingWhat).

Yoo-hoo spinoff products haven't been very successful

Part of the landscape for nearly 100 years, Yoo-hoo is a highly valuable and deeply entrenched brand name with overwhelmingly positive associations, not to mention a distinctive flavor not seen virtually anywhere else in the prepared foods game. Over the years, Yoo-hoo's makers, owners, and rights-holders have made several attempts to capitalize on and exploit that high standing in the marketplace, all by extending the brand. Ultimately, that means taking the drink's unique taste to other food and beverage segments in an attempt to appeal to previously underserved demographics.

Responding to the low-calorie craze of the '90s, Yoo-hoo created a low-sugar, low-fat version of its signature product called Yoo-hoo Lite (via Convenience Store News). It had half the calories of traditional Yoo-hoo, sure, but didn't enjoy its predecessor's robust sales and faded soon thereafter.

After the specialty coffee explosion made Starbucks a household name in the 1990s, the company very successfully teamed with Pepsi to bottle cold, sweetened coffee drinks, according to Convenience Store News. In 2004, Yoo-hoo briefly got into the pre-made sugar-coffee market with the Dyna-Mocha, a combination of chocolate Yoo-hoo and coffee. And around that same time, Yoo-hoo ventured into the frozen dessert market, introducing Yoo-hoo-based ice pops. Of those frozen treats, the Chocolate-Banana and Chocolate-Mint flavors flopped, but Chocolate and Strawberry stayed in grocers' freezers for years. As for the most visible non-drinkable item bearing the Yoo-hoo name? That would be Yoo-hoo-flavored candy.

One pope absolutely loved Yoo-hoo

Many manufacturers past and present have been lucky enough to have a high-profile and influential celebrity extol the virtues of their product. Sometimes, famous people just really love something and are willing to let the world know. That can only help increase the visibility and sales of the product in question.

Yoo-hoo, for example, had in its corner at one point a personage no less notable than Pope John Paul II, head of the Roman Catholic Church. That would be one of the world's largest religions, with more than one billion adherents, according to the BBC. Popes have to be very careful, however, about publicly disclosing their favored brands. According to ABC News, the highest of all priests does not officially endorse products.

But their preferences do come out from time to time. In 1993, Pope John Paul II made a rare visit to America, traveling to Denver for a large rally on World Youth Day (via The New York Times). On the inbound flight, reporters on the papal plane overheard the pope's spokesperson mention that he'd been tasked with obtaining "a couple of cases of that American chocolate drink" and bringing them to his boss's home and headquarters in Vatican City. Soon after, news stories about the pope's love of Yoo-hoo (clearly the "chocolate drink" in question) ran around the world. However, the spokesperson issued a statement declaring that John Paul II had no particular brand preference when it came to American-made cocoa-flavored beverages.

Yoo-hoo is great. Just take it from Yogi Berra

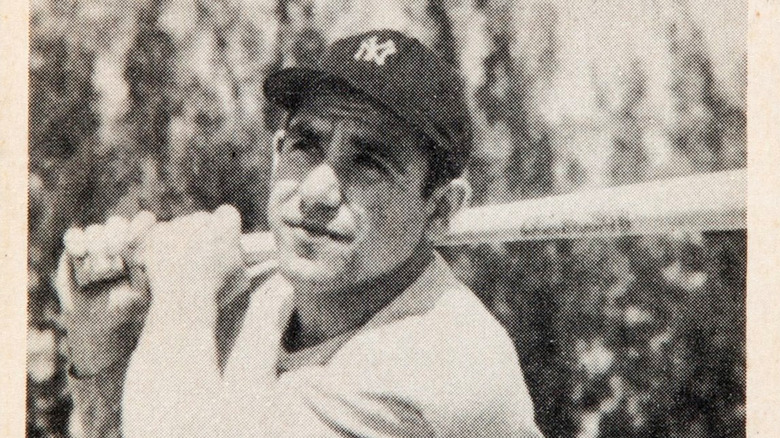

Few things evoke a feeling of the heavily nostalgized and romanticized mid-century United States more than Yoo-hoo. But baseball certainly qualifies. The 1950s and 1960s were a golden age of "America's pastime," when greats like Mickey Mantle and Ted Williams were idolized by millions and the New York Yankees dominated the big leagues. Consequently, Yoo-hoo hired Yogi Berra, a three-time Most Valuable Player, and arguably one of the most colorful baseball players of all time, to be its pitchman.

According to Roberta J. Newman's "Here's the Pitch," Berra agreed to appear in advertisements for the drink in 1955 because he was simply a fan of Yoo-hoo. And, as a notable spinner of humorously jumbled malapropisms and other witty remarks, only Berra could have effectively delivered the drink's bizarre catchphrase, "Mee-hee for Yoo-hoo!" Berra's ads, which were directed squarely at children, marked themselves as one of the first TV campaigns in which a major pro athlete endorsed a product. Berra's TV spots increased Yoo-hoo's market value to such a degree that he heavily invested in the company, and according to Brandon Steiner's "You Gotta Have Balls," he was gifted Yoo-hoo stock.

The Yoo-hoo arrangement with Berra eventually came to an end, but after ownership of the bottler moved around a few times, Berra returned to appear in a few more advertisements for the drink in the 1990s. This gave sales a considerable boost during a particularly fallow period for the brand.

In the late '90s, Yoo-hoo underwent a makeover

Yoo-hoo has major links to America's past, but the people behind the beverage have never been content to rest on their laurels. In addition to introducing new flavors over the years in an attempt to meet changing consumer tastes and demands, Yoo-hoo's bottlers have attempted to position the classic drink as cool, modern, and fresh. To that end, in 1998, Yoo-hoo took out ads in hip magazines like "Spin," encouraging teens and twenty-somethings to not only drink Yoo-hoo but to save and exchange their UPC codes to exchange for merchandise emblazoned with the Yoo-hoo logo, like bandanas, boxer shorts, and digital watches.

In 2001, according to Convenience Store News, the Yoo-hoo Chocolate Beverage Corp. even went so far as to sponsor the Vans Warped Tour, the traveling summer music festival featuring pop-punk and skate-punk bands popular with young folks. To promote the concert series and align itself with cutting-edge, hard-rocking bands of the new millennium, Yoo-hoo unveiled a limited edition series of canned drinks featuring modernly dressed, extreme sports-loving slacker characters called The Yoo-hoo Crew.

"The Yoo-hoo Crew is a caricature of teenagers doing what they do best — having fun and hanging out with their friends," Yoo-hoo marketing director Kristin Krumpe said. On a similar note, Yoo-hoo held a "World's Laziest Roadie" sweepstakes in which the grand prize was a trip to a future Warped Tour stop along with catered meals, chauffeur service, and a near-endless supply of Yoo-hoo.

A man sued the makers of Yoo-hoo for claiming it's healthy

Ownership of the Yoo-hoo brand changed hands a few times over the decades. By the 2010s, it fell under the purview of Motts LLP, part of the large portfolio of the Dr Pepper Snapple Group (now known as Keurig Dr Pepper). That meant high-priced corporate lawyers had to come up with a way to defend the company, and Yoo-hoo itself, when a New York man filed a lawsuit alleging that the company had put out false advertising.

According to the New York Post, Timothy Dahl filed suit against the makers of Yoo-hoo in June 2010 for its claims that the drink is healthy, arguing that it's nothing of the sort. "Portraying Yoo-hoo as healthy and nutritious is deceptive and misleading for kids and adults," the suit read, citing specifically the use of "dangerous, unhealthy, non-nutritious partially hydrogenated oil" in the recipe. While Motts claimed in marketing materials that Yoo-hoo is packed with "7 vitamins and minerals and no preservatives," Dahl pointed out in writing that Yoo-hoo is composed of "mostly water, sugars, milk by-products, and chemicals" and "virtually no milk."

Greg Artkop, a spokesman for the Dr. Pepper Snapple Group issued a statement, dismissing the lawsuit as "trivial," adding that "Yoo-hoo is a perfectly safe, fun treat for people to enjoy." Currently, there's no word on the outcome of the case, in which Dahl asked for $5 million in damages.