Scandals That Shook The Bourbon Industry

Bourbon is the quintessential American spirit. With a history that is thought to date back to the late 1700s, it is unsurprising that bourbon has had an interesting and sordid history. Whiskey in America has long been a topic of scandal. Arguably, this started with the Whiskey Rebellion. In 1794, disgruntlement over the allegedly excessive federal whiskey taxes imposed by Alexander Hamilton and George Washington came to a head. Protests were held and federal troops were sent in to squash the rebellion.

While fights happened in Pennsylvania, 500 distilleries in Kentucky were operational and not subject to the tax. This means that even after Congress decided to remove the whiskey tax, Kentucky was already set to be a whiskey powerhouse. Many people have come to associate bourbon with Kentucky. Roughly 95% of today's bourbon is made in Kentucky. However, bourbon does not have to be made in Kentucky. For a whiskey to be bourbon, it must be made in the United States in new charred oak barrels, composed of at least 51% corn, and have an alcohol content of between 80 and 150 proof. Bourbon's colorful history did not stop with whiskey's early, tumultuous uprising. There have been hundreds of years of scandals since.

Dispute over the first bourbon

It did not take long for the first bourbon scandal to hit. When we look back on bourbon, we cannot pinpoint its exact creator, but there are certain groups who try to claim it as their own.

There is documented evidence that a man named Evan Williams opened America's first commercial whiskey distillery in 1783 in Louisville, Kentucky. However, that was just whiskey, not specifically bourbon. From here, things get incredibly murky.

The Samuel family often gets credited for the introduction of a secret whiskey recipe in 1783. The family, who were also farmers, made corn-based whiskey. They would go on to found Maker's Mark, though with a different recipe than the original. Just a few years later, Elijah Craig would take credit for introducing the charred oak barrel portion of bourbon into the mix. And in 1795, Jacob Beam released the first barrel of what would later become Jim Beam.

The problem with all of these is that while individual contributions and evolutions were made to whiskey during this time, not one of them created the modern-day whiskey and called it bourbon. The first ad for "bourbon" didn't even show up until 1821, at which point many now-classic bourbon distillers had been established. As far as we can tell, no one gets to claim the full creation of bourbon.

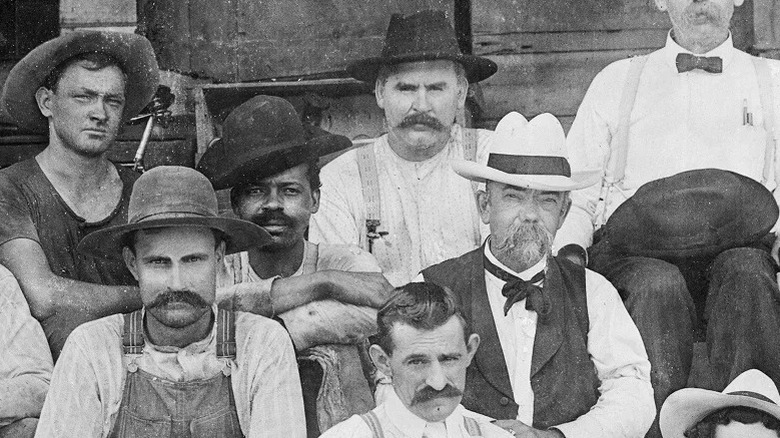

The revelation of Jack Daniel's true creator

His name is on every bottle; it has become synonymous with whiskey. But the public was shocked to find out that Jack Daniel, the man behind one of the most iconic American whiskeys, was not its actual creator. In reality, an enslaved man named Nathan "Nearest" Green taught Jasper "Jack" Daniel how to make whiskey.

Daniel and Green first met in the mid-1800s when Daniel was just 7 years old. As a young boy, Daniel met Dan Call, a preacher and distiller, who took him in. Daniel was entranced by distilling and wanted to learn everything, so Call assigned Green to teach Daniel the art of whiskey making. Green was an exceptional distiller. He taught Daniel a charcoal filtration method that is thought to have been inspired by a similar West African water filtration technique. It was this technique that helped Daniel market his smooth whiskey, eventually allowing him to buy Call's distillery and build his empire.

After the Civil War, Green and Daniel stayed together, this time in a partnership where Green was recognized as the master distiller. Today, he is still considered the first African American master distiller in the United States. Green's descendants worked for the company for generations after and still do today.

But for most of Jack Daniel's history, Green was ignored. That is until Fawn Weaver uncovered the truth and made it her mission to bring Green's legacy the respect it deserves.

When Jack Daniel's changed the regulations for what counts as bourbon

Perhaps you're thinking, "Isn't Jack Daniel's a Tennessee whiskey, not bourbon?" And to that, we say, "Yes, but there's more to it." Jack Daniel's only has this categorization because it convinced the U.S. government to change laws around naming so it could use the term "Tennessee Whiskey." By the company's own admission, it meets every single qualification to be considered a bourbon. Jack is made of a corn mash in America, in new charred oak barrels, and with the necessary ABV. For all intents and purposes Jack Daniel's is a bourbon. So, what happened to get it to shed the designation?

It all began back with the repeal of Prohibition laws. With that repeal came the implementation of newly defined categories of liquor. Let's remember that Tennessee Whiskey, unlike bourbon, is not a federally designated product. In fact, it did not become a state-defined product until 2013.

Because Jack Daniel's meets all the requirements to be a bourbon after the government initially told the company that it had to use the bourbon label. The company was unhappy about this and sent the pertinent bureaucrats bottles of its totally-not-a-bourbon whiskey to persuade the government to change the rules and not force Jack Daniel's to classify itself as a "bourbon." And in 1941, it worked. It is impressive that Jack Daniel's can change the definition of bourbon while claiming that they make something else.

Bourbon as medicine

Prohibition was a dark time for bourbon. In the late 1800s, there were hundreds of varieties of bourbon in Kentucky. After prohibition, the numbers dropped considerably. When people think of the Prohibition era, they often think of speakeasies and moonshine, but they weren't the most interesting aspects of how alcohol was produced and sold. Legend has it that Joe Beam, for example, literally took his plant apart in Kentucky and put it back together in Mexico. We truly admire that level of dedication.

Another was to go an arguably even more unconventional route. There was a loophole in the Prohibition laws that allowed alcohol to be made for medicinal purposes. You could literally get a prescription for up to 1 pint of whiskey per 10-day period. Six distilleries were licensed for this, including Brown-Forman, Frankfort Distilleries, and American Medicinal Spirits, which made bourbon. Producing bourbon this way meant the companies got to keep producing, weathering the storm of what we now know was a 13-year time period.

The great Pappy Van Winkle heist

Perhaps the most notorious scandal to ever hit the modern bourbon industry was the great Pappy Van Winkle heist. The story was so juicy and enticing that Netflix covered it in its docuseries "Heist."

In 2013, it was discovered that 65 cases of Pappy Van Winkle bourbon were gone without a trace. For those unaware, Pappy Van Winkle is no ordinary bourbon; it is among the most expensive bourbons available. In the investigation, it was discovered that Pappy Van Winkle was not the only product stolen from the company — investigators uncovered indications of stolen bourbon dating back to January of 2008.

To make matters more intriguing, Buffalo Trace, the company that distributes Pappy Van Winkle, has specific rules for some of its products. Customers are limited to just one bottle of certain brands from the distillery, and distributors only receive a limited supply. These are known as "allocated" bottles. This further ups the value of black-market Buffalo Trace-produced products.

It was discovered that a ring of people, including long-time Buffalo Trace employee Gilbert "Toby" Curtsinger, were stealing bourbon in quantities totaling over $100,000 from the company. Interestingly, while Curtsinger admits to stealing bourbon, he denies being behind the missing Pappy Van Winkle cases. Curtsinger was sentenced to 15 years in prison, though he served just 30 days, for his involvement in what is now known as "Pappygate."

The Oregon Pappy Van Winkle swindle

Pappy Van Winkle just cannot catch a break, it seems. Something about being an expensive and limited product just entices people to break laws, and when you are a "control state" like Oregon, it makes liquor crimes all the more attractive.

In February of 2023, it came to light that high-ranking officials in the Oregon Liquor and Cannabis Commission (OLCC) had used their power to keep coveted bottles of Pappy Van Winkle out of public hands and in the hands of OLCC officials. As discussed, Pappy Van Winkle is both expensive and hard to find. Each year, just 84,000 bottles of Pappy Van Winkle hit the market. That might sound like a lot, but it's nothing compared to more prominent brands whose output is well into the tens of millions of bottles per year. The distillery in charge of Pappy Van Winkle must carefully allot the limited number of bottles produced. So, siphoning off bottles means the rest of the state has to go without.

The officials rigged the system, sending the state's Pappy Van Winkle supply to one state store near their office. The bottles were held in storage until they got there, where the officials would buy them at face value. They also completely bypassed the state's lottery system, where consumers win the ability to purchase these rare bottles. Of the 999 bottles received by the state of Oregon in 2022, just 150 made it to the public. OLCC employees scooped up the rest.

Virginia's allocated bourbon scandals

Oregon wasn't the only control state experiencing difficulties in 2022. Virginia also had a bourbon scandal and once again, we see popular but elusive bourbon at the heart of this story. When allocated products such as Buffalo Trace come into stock, places such as Virginia have to find a way to distribute the limited supply equitably. To do this, Virginia sent bottles to seemingly randomized locations.

Edgar Smith Garcia, a lead sales associate for the Virginia ABC stores, used his access to state computers to find out where bottles would be sold. He then gave this information to Robert William Adams, who sold the information to bourbon lovers for $300.

The scheme didn't last long. Pretty soon, complaints of people selling the information started popping up on ABC's Facebook page. What was first thought to be a conspiracy theory turned out to be true. That got both men responsible arrested for their actions.

Similarly, Virginia recently had problems with its bourbon lottery system. In this case, multiple people won the right to multiple bottles, which is statistically improbable. Representatives for the state admitted this was an error but did not believe there was deliberate tampering with the system.

Justins' House of Bourbon's questionable acquisitions

When it comes to getting your hands on allocated bottles, companies are just as anxious to get hands on them as individuals. This thirst for allocated bottles rocked the bourbon world when Justins' House of Bourbon was accused of illegal actions, including unlawful alcohol transport and selling counterfeit bottles.

Justins' House of Bourbon was originally a Kentucky-based company but expanded to locations outside the area, including one in Washington, D.C. This is where the trouble began. The D.C. Alcoholic Beverage Regulations Administration brought 11 total violation allegations against Justins' House of Bourbon. Justin Sloan, co-owner of the business, told Whiskey Advocate that the reports were made because they seemingly had too many bottles of allocated alcohol.

In the initial investigation, it was found that Justins' was importing bottles of Blanton's bourbon from the Netherlands. The report alleged that the imports were done incorrectly and that the supplier for another bourbon, Weller, didn't seem to have a license. Another report claimed that the Blanton's bottles were counterfeit.

The case has since been resolved and Justins' was cleared of many important allegations, such as counterfeiting. Justins' was hit with some minor fines for things such as bookkeeping issues, but that's about it.

When Wilderness Trail Distillery couldn't produce

We all overcommit sometimes. Thankfully, though, for most of us, being overcommitted does not turn into a lawsuit that ends up being headline news. Unfortunately, that is exactly what happened to Wilderness Trail Distillery when it failed to deliver promised whiskey barrels to Washtucky Holdings.

Here's what happened and why it caused so much drama: The Campari Group bought a controlling share of Wilderness Trail Distillery. Campari wanted to use the company's bourbon to expand its own bourbon output. The problem was that 12,500 barrels of Wilderness Trail Distillery 10-year-old bourbon had already been promised to Washtucky Holdings. And you can't exactly just make another few barrels of a product that's been aging for 10 years.

Washtucky initially made a deal with Wilderness Trail in 2020 in which it agreed to pay a specific price per barrel for up to 40,000 barrels. The first portion of the deal went off without a hitch, but when Campari took control of Wilderness Trail, the distillery stopped fulfilling the demand.

Washtucky looked at the barrels as an investment and claimed it lost out on money due to the lack of whiskey. Washtucky expected to triple its money on each barrel of bourbon.

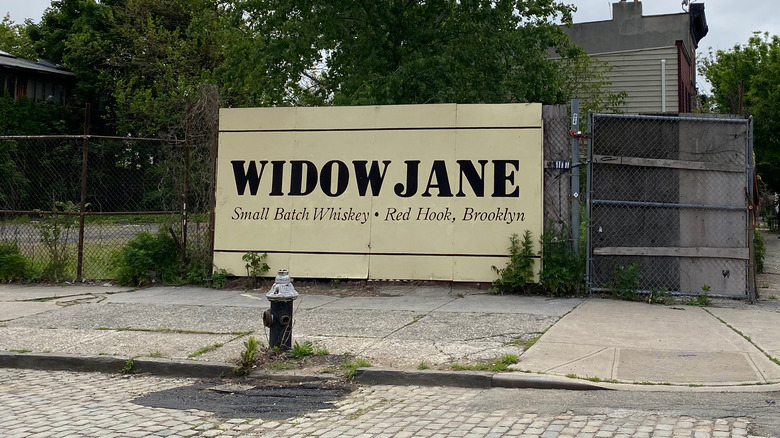

The shocking truth of sourced bourbon

When you buy a bottle of bourbon, it creates an image in your mind of a picturesque distillery crafting its alcohol and aging with care. This is intensified when you think of so-called "small batch" bourbon. The truth, though, will shock you.

Many companies, including recognizable brands, use sourced whiskey. This means buying barrels from producers and bottling them as its own. This is not a new technique and has been used in other whiskey-making endeavors, such as blended scotch. When it comes to bourbon, though, it is possible that instead of getting whiskey from the distillery you've been led to think it's from, you get whiskey from a barrel made by other companies such as MGP. MGP has distilleries worldwide and produces an immense amount of bourbon. MGP also only sells to companies, not to individuals.

One such company that uses sourced barrels is Widow Jane. This is particularly eye-opening as part of Widow Jane's allure is the use of water from the Widow Jane Mine. While Widow Jane does distill some products, the company has also reportedly used bourbon from a Kentucky distillery.

When the bottle lies

Your bottle could be lying to you. With all the regulations around what legally does and does not constitute bourbon, you may be surprised that some of the language on bottles is misleading, if not bald-faced lies.

So-called "small batch" bourbon has become increasingly popular, yet it means absolutely nothing legally. The same thing goes for "hand-crafted" and the derivative "craft." What is even more surprising is that brands can label a bottle as "made by" anyone. This is how you get companies that use sourced whiskey and pass it off as made by the company. Colin Spoelman, master distiller at Kings County Distillery, described the industry to NBC as "just a shady business."

Sometimes, of course, this kind of marketing does come to bite a company in the behind. In 2014, the bourbon company Maker's Mark was sued over the use of "handmade" when there are, in fact, machines that do things such as grinding the grain. Around the same time, Templeton Rye faced a class action lawsuit for misrepresenting various aspects, such as where the whiskey was made. It is nice to know that other types of whiskey are subject to scandals similar to bourbon's.

When the whisky wasn't protected

Scandals aren't all bad. Sometimes they lead to good things. The 19th century was rampant with low quality and sometimes dangerous alcohol. Bourbon was one of the biggest offenders — colors and flavors were added to make phony bourbon appear to be the real thing. This led to the creation of the 1897 Bottled-in-Bond Act. This was a federally set standard for whiskey that required bottles to be made by the same distillery and aged at least four years; additionally, the whiskey could not have anything except water added to it and had to be exactly 100-proof. These strict guidelines made up the first consumer protection laws in the United States.

This meant great things for whiskey in general and bourbon in particular, as any bottle labeled Bottled-in-Bond met those standards and helped push the imposters out. This idea was further expanded in 1906 when the Pure Food and Drug Act defined straight, blended, and imitation whiskey. But, of course, with no federally protected standard, people were still calling whiskies "bourbon" without them meeting today's standard.

After the repeal of Prohibition, bourbon finally got its own designation, and in 1964 bourbon officially became an American-only product. While fake whiskey is not what anybody wants, we can thank all those forgers for giving us the bourbon we love today.