You'll Never See These Bread Brands Again

Bread is a staple of the Western diet, with hundreds of varieties traditionally popular throughout almost every region of Europe and North America. Once something that households had to bake individually at home several times a week, bread (and buns, rolls, and the variants) was reinvented in the modern, industrial-minded age into an inexpensively purchased grocery item. Even the smallest market or convenience store virtually anywhere stocks at least a few different styles and brands of bread, from white to wheat to potato to rye to kinds filled with seeds and nuts to ones sweetened with honey.

It's big business to make bread, and national and regional bakeries alike give the people what they want day in and day out, year after year. That is, they do until suddenly, almost out of the blue, the breads that the companies have spent a lot of resources building up brand loyalty for disappear from shelves. Here are some very famous, very popular, and very important breads that millions counted on for their toast and sandwiches until their bakeries sadly stopped producing them.

Old Home Bread

Not many regional bakeries help spawn a pop culture craze or inspire a multiple pop hits, but Metz Baking Company did. In 1973, Metz, a then-51-year-old bakery originating in Sioux City, Iowa, hired Omaha, Nebraska, ad agency Bozell and Jacobs to launch a TV commercial campaign for its Old Home Bread. Executive Bill Fries took the task and, assuming the persona of a truck driver named C.W. McCall, created and starred in 12 commercials for Metz. A dozen ads told the ongoing love story of McCall, a truck driver (who so romanticized the use of his C.B. radio it helped launch a fad around the communication device and trucking), and Mavis, a server at the Old Home Filler-Up an' Keep-on-a-Truckin' Café. The ads sold bread and buns but were so popular that Fries recorded and released multiple songs in character as C.W. McCall. One of them, "Convoy," hit #1 on the Billboard Hot 100.

By the late 1990s, Metz Baking was a subsidiary of Midwestern food giant Special Foods that sold $600 million worth of product a year. That year, another big baking company, Earthgrains Co., bought Metz for $625 million in order to attain a more dominant market share in bread and buns in Milwaukee, Chicago, Minneapolis, Detroit, Salt Lake City, Kansas City, Omaha, and Des Moines. In 2001, Sara Lee bought Earthgrains and discontinued Old Home Bread.

Goldfish Bread

For decades, Pepperidge Farm's Goldfish crackers were a simple affair: bite-sized crackers shaped like fish. Introduced in 1962, they didn't taste anything like fish but were initially available in one of five mild flavors: Lightly Salted, Cheese, Barbecue, Pizza, and Smoky. The enduringly popular variety, Cheddar Cheese, came along in 1966. In 2011, arguably the strangest Goldfish cracker product hit stores — because it wasn't in any way a cracker.

A new product arrived on grocery store shelves in 2011: Pepperidge Farm Goldfish Sandwich Bread Soft White. It was sandwich bread meant to appeal to the same demographic who enjoyed non-fussy Goldfish crackers — children. The bread came eight to a package, presented like a bun or hoagie roll. Each piece was free of crust and adorned with a smile, like the crackers. Unlike the crackers, the Goldfish bread wasn't cheese-flavored. The product didn't catch on and quietly disappeared. Pepperidge Farm no longer offers the bread for sale.

Bond Bread

In a 1922 advertisement in the Saturday Evening Post, the makers of Bond Bread (the General Baking Company) boasted of having served more than 25 million happy customers at 50,000 grocery stores. And that's after having been in business for just seven years. The Bond Baking Company claimed to use very high-quality ingredients, and very few of them, making for a product that was comparable to "the best home-made bread," created with just flour, lard, sugar, salt, milk, and yeast.

By the late 1970s, Bond Baking Company was the last big industrial bakery in the Philadelphia area, with four satellite facilities in nearby New Jersey. Things started to go stale in July 1978, when the company filed for protection under federal bankruptcy laws. An effort by executives to turn the company profitable quickly failed, and, unable to pay the $750,000 bankruptcy costs, Bond closed its four secondary bakeries in New Jersey in April 1978, laying off 133 people. Weeks later, it shuttered the flagship Philadelphia bakery, putting 600 people out of work. Just like that, no more Bond Bread was ever baked again.

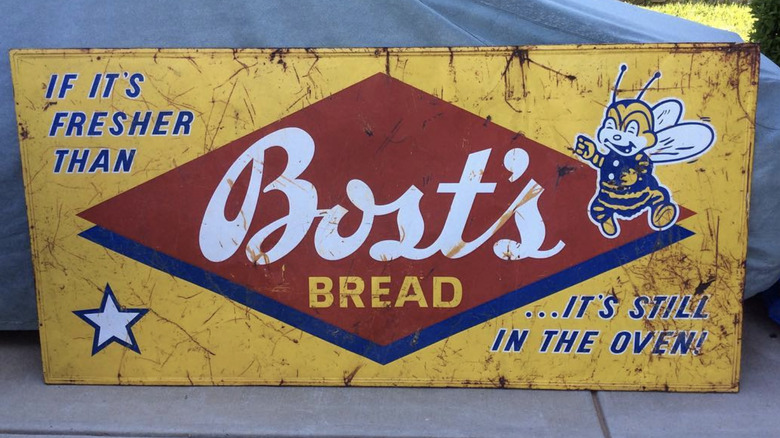

Bost's Bread

Bost's Bakery was a family-owned bread-making operation that for years operated out of Shelby, North Carolina. L.C. Best created the company, and his four sons ran it for decades. "If it's fresher than Bost's, it's still in the oven," was the brand's catchphrase on local commercials that aired on local television stations in the area in the mid-20th century.

In the early 1960s, Bost Bakery expanded, building a 66,000-square foot production facility in Thomasville, North Carolina, to meet demand for its bread, distributed by then throughout the upper South. About 2,000 people worked at the facility even into the 1970s when Continental Baking, one of Bost's national competitors and the makers of the bestselling Wonder Bread, bought out the whole operation. Wonder's operators kept the Thomasville plant going, and Bost's Bread on shelves, up until the 1980s, when it closed down the factory and eliminated Bost's from its portfolio of brands.

Franz Poulsbo

Englebert, Joseph, and Ignaz Franz purchased their uncle's Portland, Oregon, company, United States Bakery, in 1907, and turned it into Franz Bakery in the 1920s. Throughout the 20th century, Franz would be a leader in bread and baked goods across the Pacific Northwest. Responding to changing and expanding market tastes, by the 1980s, Franz would introduce its version of Poulsbo bread. Named after a city in western Washington, it was among the first widely available whole wheat, and grain-oriented breads on the market, serving as a counter to Wonder-type white breads. It quickly became one of Franz's most popular upscale varieties.

Franz made a fatal error with Poulsbo in that it opened up the market in its Pacific Northwest territory for more interesting sandwich bread. "We're a victim of our own success. When that bread was brought onto the market, there wasn't a lot of different types of whole wheat and heavy grain breads available," Franz representative Lisa Clarence told the Kitsap Sun. "Most people were eating the very basic vanilla, white bread and to have something with all of those grains and nutty flavor was very different and now there are many, many types." Those competitors' offerings outsold Poulsbo to the point where Franz repeatedly dropped and reintroduced the bread from its lineup three times in the 2010s, ultimately eliminating it completely in 2014.

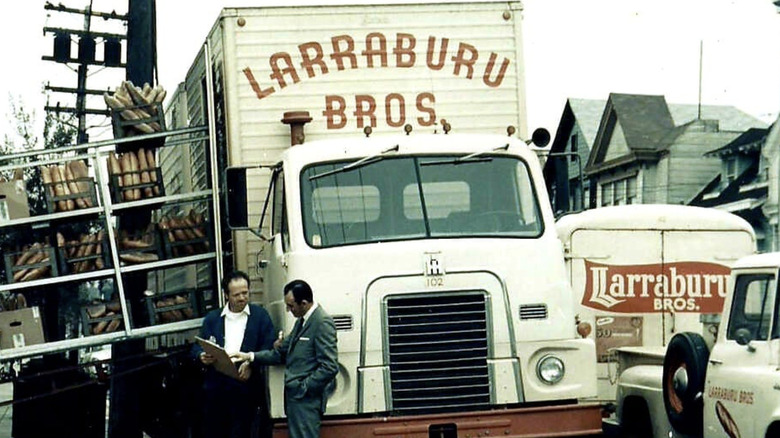

Larraburu

Sourdough bread is essential to the cuisine and food history of San Francisco. Numerous local bakeries over many decades have produced their own beloved versions of the uniquely bitter and creamy bread, chief among them Larraburu. San Francisco Chronicle columnist Herb Caen included a loaf of Larraburu bread as part of the hypothetically perfect San Francisco meal, as the bakery operated in the Bay Area for more than seven decades. The Larraburu brothers immigrated to San Francisco from France in 1896 and went into competition with local stalwarts Toscana, Boudin, and Parisian. They carved out a niche with their bread baked with a special sourdough starter made from a live culture. By the mid-1960s, Larraburu sourdough was popular with locals and tourists alike; the San Francisco airport sold 1,500 loaves a week in 1964.

Nevertheless, in the early 1970s, Larraburu filed for bankruptcy. The company had recovered and was beginning to expand again when one of its delivery drivers hit and injured a child. Larrraburu couldn't come back from the financial problems resulting from years of courtroom battles and citing overwhelming debt, the bakery went out of business and ended production of its bread in May 1976.

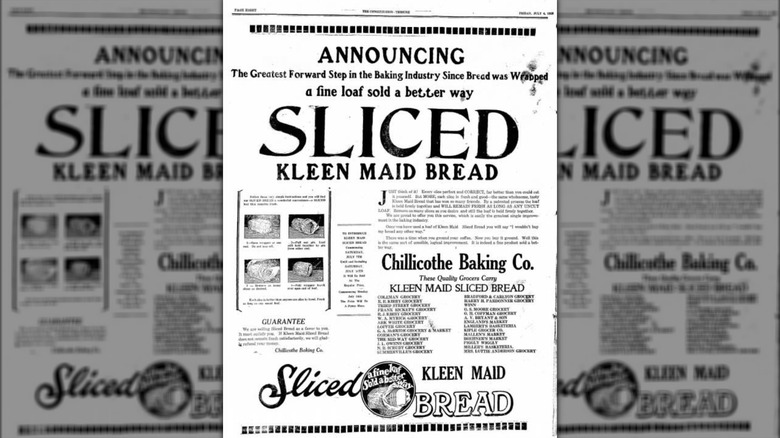

Kleen Maid

The commonly uttered superlative "the greatest thing since sliced bread" dates to a particular moment in time. It entered use in 1928 as a variation on some ad copy that appeared in a Chillicothe, Missouri, newspaper promoting locally-produced Kleen Maid bread, "the greatest step forward in the baking industry since bread was wrapped." Marion "Frank" Bench's Chillicothe Baking Company became the first commercial bread-maker in the U.S. to sell loaves of bread already sliced into individual servings. Iowa jeweler Otto Rohwedder invented an automatic bread-slicing machine in 1917, but couldn't get any bakeries to adopt the technology until the late 1920s, when Bench, an old friend, decided to use the gadget. As a marketing gimmick, it worked, and sales of Chillicothe's pre-sliced product, Kleen Maid, were healthy for a few years before other bakeries started slicing bread, too — particularly competitor Continental Baking Company with its Wonder Bread.

Despite fundamentally altering the way bread was sold, packaged, and purchased, Bench's bakery couldn't weather the financial devastation of the Great Depression. He had to shut down the Chillicothe Baking Company in the 1930s, less than a decade after it became the first commercial bakery to offer pre-sliced bread.

Dorsch's White Cross Bread

As early as the 1920s, one of the top-selling breads in and around Washington, D.C. was Dorsch's White Cross Bread. Upon establishment in the 1800s, Dorsch's first production facility was a shed, with bakers churning out only a few loaves each day. Within three decades, it operated out of an urban factory where it could make as many as 100,000 loaves of White Cross and other varieties each day.

Taggart Baking invented Wonder Bread, which helped popularize fortified white bread to the point where it changed the way bread was distributed in the United States. After acquiring other, regional bakeries, Continental Baking Company bought Taggart in 1925 and became the biggest baking concern in the United States. In part to build up Wonder Bread into a national brand, Continental bought other regional and local bakeries around the U.S. whose business it diminished with its ability to bake and distribute inexpensive, pre-sliced bread. In the 1940s, Continental purchased Dorsch's to close it down and use its D.C.-area facilities to bake Wonder Bread and other products.