The Untold Truth Of Gold Medal Flour

You might not think much of where your flour comes from. Maybe you check to make sure a particular flour is the best fit for your baking project or that it's the right choice for your dietary needs, but you might not otherwise look that closely at a particular flour brand's origins or history. However, if you peek a little further beyond that paper flour bag, you might just see something more than just a building block for your favorite sweet treats. Such is the case with Gold Medal, a flour brand that revolutionized the milling industry in the 1800s and that's connected to some of our favorite pop culture icons, such as Betty Crocker and the Pillsbury Doughboy.

So don't just assume that flour is flour. When it comes to Gold Medal, this brand's story is an intriguing bit of history worth a quick read. You'll never look at that blue and gold bag the same way again.

General Mills created the Gold Medal brand

Okay, maybe it wasn't precisely General Mills. Instead, it was General Mills' predecessor, the Washburn-Crosby Company. According to Gold Medal and General Mills' history, Cadwallader Washburn (yes, an unfortunate name) built his first flour mill in Minnesota in 1866 along the powerful St. Anthony Falls on the Mississippi River. This initial mill was six stories tall, with 12 pairs of millstones, and it could produce about 840 barrels of flour per day.

Even back then, Washburn's millers were at the forefront of the industry. At the time, Minneapolis flour mills were known for producing dark flour made from spring wheat, even though white flour was more popular with consumers. A Washburn miller created a "middlings purifier," a device that would remove the dark grain husks from the flour as it was processed, resulting in that stark white hue that consumers preferred. The change benefited not only the Washburn-Crosby Company, but also other Minneapolis millers who took advantage of the technology, and Minneapolis would stand as the world's top flour producer for the next half-century.

A flour dust explosion destroyed the first mill

Cadwallader Washburn's mill was a success, but before long, tragedy struck: A flour explosion occurred in 1878, completely destroying the original mill and killing nearly 20 people. The explosion was so devastating that, as HafcoVac (a manufacturer of industrial vacuums that are designed to reduce explosions like this) says, the industry has been trying to reduce the risks of these explosions ever since.

We know what you're thinking. A flour explosion? How in the world does an innocent pantry staple like flour explode? As HafcoVac explains, flour explosions are usually the result of a combination of large quantities of flour dust, an ignition source, oxygen, and a confined space, among other things. And, yes, flour dust is combustible; in fact, HafcoVac says it's "more explosive than gun powder and 35 times more combustible than coal dust."

While today, risks of these explosions are lessened thanks to employee training, changing working conditions, and flour dust extraction systems, they're hardly a thing of the past. As recently as 2018, a flour dust explosion in Nebraska injured two people (via The Argus Leader).

The next mill was bigger and better than ever

Within two years after the flour dust explosion, however, Cadwallader Washburn had rebuilt his mill — but not without a large amount of criticism. The new mill, as Gold Medal describes, was considered too big to be successful. Washburn would never be profitable and the mill would make more flour than it could sell, the circulating rumors proclaimed.

Not only did this prediction prove untrue, but the new mill introduced better technology that reduced the risk of future flour explosions. According to General Mills, Washburn used the expertise of a Bavarian engineer to create new explosion-preventing technology after the destruction of his first mill. Although he could have kept these innovations to himself, he shared the technology with other mill owners. He wanted the flour industry as a whole to benefit from his technology, saying, "My mills are only a small part of the whole. I can't make all the flour people want, even if I wished to."

Gold Medal Flour wins its first gold medal

Up until 1880, Gold Medal Flour was known as Superlative Flour, but that would change after Cadwallader Washburn took his Superlative Flour to the First Millers International Exhibition. There, Superlative Flour was graded alongside flour from millers from all over the world. According to Bakery Online, not only did Superlative Flour win the gold medal in its category for spring wheat patent process flour, but Washburn's lower grades of flour also won silver and bronze. After winning this award, Washburn decided to change his flour's name from Superlative to Gold Medal and began shipping out flour with that branding as early as August 1880, only a few months after the First Millers International Exhibition concluded.

Both the awards and the branding worked in Washburn's favor, and Gold Medal Flour became more popular than ever. That popularity would kickstart marketing efforts that the brand would become known for over the next century, as well as inspire other millers to follow in Washburn's footsteps.

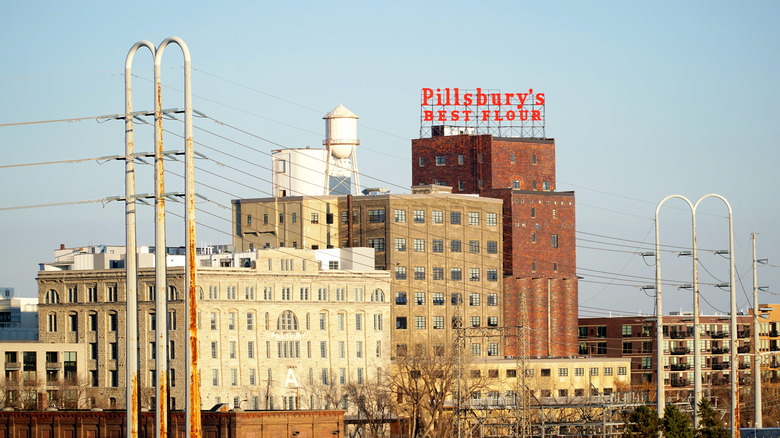

Charles Pillsbury takes a hint

When Cadwallader Washburn was building his large mill and pioneering technological advances in milling, Charles Pillsbury was taking notes. He decided to get into the milling business himself and purchased a mill right across the river from Washburn (via General Mills). While his business track record wasn't the greatest and he didn't have any experience in the milling industry, Pillsbury still managed a profitable first year and became one of Washburn's largest competitors.

Like Gold Medal, Pillsbury flour was advertised as the best flour on the market. Starting in 1872, Pillsbury packaging included a distinctive "XXXX" trademark. The four X's were a spin on the triple X's that would be used in medieval days to mark flour that was of such good quality that it could be used for religious ceremonies. Since Pillsbury thought his flour was even better than that, he tacked on an extra X.

Gold Medal switches from barrels to bags

Around the turn of the 20th century, millers began to swap out their old flour barrels for bags, trading wooden barrels for paper or hand-sewn fabric. According to the Minnesota Historical Society, while the past barrels were created using Minneapolis white pine, the new cloth and paper options were created in factories, by women laborers. Flour began being packaged in bags in the 1860s, but the move away from barrels happened gradually.

The bags came with many benefits. They were cheaper to manufacture and ship than wooden barrels were. They also changed how flour was sold. Traditionally, consumers would tell a grocer how much flour they wanted, and the grocer would scoop it out of a barrel and package it up for them at the store. The bags allowed customers to buy small amounts of factory-packaged flour. Additionally, the cloth bags could be recycled and repurposed into household items such as towels and even clothes.

Marketing and advertising spread Gold Medal's fame further

Advertising was a big part of the milling industry, and the two large competitors, Washburn-Crosby and Pillsbury, were some of the largest advertising players in the country. As early as 1889, Washburn-Crosby was sending out the historical equivalent of posters to flour buyers and shipping agents, to hang in their offices. By the time the 1900s rolled around, Gold Medal was advertising directly to consumers through unique marketing materials such as trade cards, pamphlets, calendars, envelopes, and package inserts. Just like today, the marketers were smart and attempted to appeal straight to their buyers; they featured images of women in their marketing materials in an attempt to court female consumers. In 1907, Washburn-Crosby would produce its most famous slogan, "Eventually — Why Not Now?"

Pillsbury, meanwhile, was hot on Gold Medal's tail, with the slogan, "Because Pillsbury's Best," appearing in magazines and ads. They placed advertisements in popular women's reading materials such as the Ladies' Home Journal.

Gold Medal Flour founds its own test kitchen

In the 1920s, Gold Medal became even further entrenched in the lives of its consumers by founding a test kitchen and providing useful content — not just ads — to its target audience. The test kitchen brought in home economists to test the flour in a range of baked goods, and supposedly verified the quality of flour shipments before they were sent out into the world. Meanwhile, the Gold Medal Home Service Department answered consumers' flour-related questions (via Gold Medal).

The Department also produced recipes. One antiquer and writer for My San Antonio describes discovering one of the Department's recipe boxes in 2012. She could tell that the box originated between 1921 and 1928, as it featured Betty Crocker, but predated Washburn-Crosby's rebranding as General Mills. The box included an original label inside the lid depicting a Gold Medal flour bag and the Washburn-Crosby Co. name. The box also included recipe cards and dividers, and even a card that gave the owner instructions on how to obtain more recipes: by buying more Gold Medal flour, of course. Each bag of flour included a coupon that consumers could mail in with a $0.02 stamp to receive a new set of seasonal recipes in return.

Washburn-Crosby creates Betty Crocker

"Eventually — Why Not Now?" may have revolutionized flour advertising, but one of the Washburn-Crosby Co.'s largest marketing schemes was the invention of a household name: Betty Crocker.

Crocker came about in 1921 as a result of one of the company's other marketing campaigns (via PBS). Gold Medal had placed an ad in The Saturday Evening Post that included a puzzle. If readers completed the puzzle and mailed it in, they'd receive a pincushion shaped like a bag of flour. Many of the returned puzzles, though, also included letters with baking-related queries. The company's all-male advertising team sourced answers to these questions from the women who worked in the test kitchen, sending out the responses in letters. Marketing manager Samuel Gale didn't want to sign these letters with his own name, so the company created Betty Crocker.

From there, the Betty Crocker name was used in letter responses, as well as in a cooking radio show that aired in 1924. Betty Crocker didn't actually appear on any grocery items until 1941, though, when Washburn-Crosby Co. added her to a soup mix, and then later a cake mix — the item for which she's likely most well-known today.

Washburn-Crosby becomes General Mills

No one really knows the Washburn-Crosby Co. name today. Instead, they know General Mills. So how did this name change come about?

According to General Mills, in 1928, Blair & Co., an underwriting firm in New York, offered to purchase Washburn-Crosby Co. for $40 million, and leadership took the deal ... until one member of that leadership team called off the sale. So, leadership decided to reshape the company rather than sell out. They looked for new investors and pitched the idea of a new kind of milling company, one that wasn't so reliant on merely flour, and, later in 1928, Washburn-Crosby started anew with the General Mills name, going public on the stock exchange at $65 per share. While the upcoming Great Depression was devastating for many brands, General Mills managed to not only survive, but thrive, offering new items such as Bisquick, Kix, and Cheerios, and amping up its marketing efforts.

General Mills continues to innovate

Today, bread (and products made from wheat flour in general) gets a bit of grief for being "unhealthy" and "full of carbs." It wasn't always this way; Gold Medal boasted proudly in a huge mural on one of its mills, "Eat More Wheat, Your Best Food" (via Gold Medal). The greatest milling industry innovation during the 1940s was the addition of enrichments to flour, as studies proved that many Americans were not getting the nutrients they needed from their diets. Gold Medal followed the U.S. government's recommendations and added extra nutrients to its flour.

This period was the first time that U.S. doctors and scientists had specifically identified deficiency disease syndromes. In 1941, the FDA established a strict standard for what could and couldn't be considered "enriched" flour (via the National Center for Biotechnology Information). These enrichment standards would go on to impact the production of white bread. By 1942, manufacturers were enriching 75% of the white bread they produced.

General Mills expands its flour (and other) offerings

Although Gold Medal is General Mills' flagship product and is the top consumer-branded flour and the top brand of sack flour in commercial baking, it's not the only flour that General Mills had on offer through the mid-1900s. A range of other flours came on the market, including No Sift Flour in 1961, Wondra Flour in 1963, and Better for Bread Flour in 1979 (via Bakery Online).

However, General Mills was far beyond a milling-based company by this point. In 1946, General Mills established an aeronautical research laboratory that assisted the U.S. military (via General Mills). It went into the appliances business. It made countertop kitchen aids, from mixers to coffee makers. It stuck its fingers in submarines and toys and clothing. Still, a portion of the company kept its focus on flour, creating the Bellara Air Spun process in the 1960s as a means of creating more uniform, higher-quality flour.

Gold Medal today

Today, Gold Medal offers eight different types of flour: all-purpose, bread, organic all-purpose, self-rising, unbleached all-purpose, white whole wheat, whole wheat, and Wondra Flour (For those that don't know, Wondra Flour is designed to dissolve in liquids faster, creating a smoother and less lumpy texture in things like gravy). And, of course, Gold Medal is still offering tips, tricks, recipes, and advice to help home cooks around the kitchen. You won't, though, find Betty Crocker anywhere on the Gold Medal site; she's been spun off into her own brand, one of many beneath the General Mills umbrella. Gold Medal additionally isn't quite the marketing master that it once was. A quick look at the brand's Twitter page shows a paltry 2,350-plus followers, compared to the 144,000-plus users who follow Pillsbury (which, incidentally, is now also part of General Mills, according to Britannica).

Gold Medal Flour might not be as prominent as it was in the early 1900s, but one thing's for certain — no one can deny that this was the product that launched the General Mills empire.