The Untold Truth Of Subway Co-Founder Fred DeLuca

He co-founded Subway, one of the world's largest fast-food chains, but he ran it like a family business. He was a billionaire, but he was notoriously stingy, driving an old Lincoln, flying coach, and berating his daughter-in-law for shopping at Whole Foods. And yet he owned a mansion so lavish that rapper Sean "Diddy" Combs asked to feature it on the front cover of his album.

Fred DeLuca was a man of contradictions. Even though he died in 2015 at the age of 67, the repercussions of his business practices are still felt in Subway's operations. He maintained an iron grip on Subway, insisting until 1990 that he sign every company check personally and refusing to give his co-founder an office at corporate headquarters.

Workers were "swimming in a fountain of Fred," a former employee told Insider. "He was very smart and hardworking, but one of the problems was that he ran the franchise when we had 30,000 stores as if we had a hundred stores."

Here's the untold truth of Fred DeLuca, from his modest beginnings to the power vacuum left in the wake of his death.

DeLuca started Subway when he was 17 years old

Born in Brooklyn in 1947, Frederick DeLuca lived in public housing with his parents and younger sister. When he was 10, his family moved to Schenectady and then to Bridgeport, Connecticut, where he graduated from Central High School in 1965.

Aspiring to study medicine, DeLuca worked at a hardware store. But he knew he would not earn enough to pay for college. According to Business Insider, in his book "Start Small, Finish Big," DeLuca wrote that he hoped a family friend, Peter Buck, would offer to pay his tuition. Buck, 35 at the time, was a nuclear engineer for General Electric. When DeLuca broached the topic, Buck proposed that they open a sandwich shop together instead.

That August, DeLuca rented a small storefront in downtown Bridgeport for $165 a month. He named it Pete's Super Submarines in acknowledgment of Buck's startup capital. DeLuca later changed the name because when he read "Pete's Submarines" in radio ads with his Brooklyn accent, listeners thought he was saying "Pizza Marines." The name became Pete's Subway before being shortened to just Subway.

DeLuca failed at first, then found a winning formula

From Subway's infancy, DeLuca relied on family members to help. His mother Carmela Ombres DeLuca hosted Monday meetings at her kitchen table. After a dinner of homemade spaghetti and meatballs, the DeLucas and Buck would discuss how their weak sales continued to worsen. Nevertheless, they opened a second shop "to create the image of success," DeLuca told Fortune.

DeLuca and Buck shared a growth mentality, setting a goal to own 32 stores within a decade. According to The New York Times, by 1974, they were halfway there, having adopted a franchise model which proved the key to their success. In 1978, Subway opened its hundredth outlet, and in 1987, its thousandth.

With startup costs ranging from $116,000 to $263,000, compared to $1-2 million for a McDonald's location, Subway stores were relatively easy for new franchisees to open. In exchange, franchisees agreed to hand over 8% (now 12.5%) of gross sales along with other fees and stipulations.

Today, Subway owns zero stores. While a franchisee's profit is tied to sales, the corporate franchisor makes its money from royalties and fees. More stores mean higher profits, even when individual locations struggle.

DeLuca was a known philanderer

A year after finishing high school, DeLuca married his sweetheart Elisabeth. She served as an officer in Subway's early years but retired in the 1980s. In the book he published in 2000, DeLuca wrote, "I joined a fraternity, I dated Liz, and I had a good time in college." He didn't write much else about her.

When Connecticut instituted a personal income tax in the early '90s, DeLuca moved to Florida to avoid paying it, while Liz stayed in Connecticut. The pair would attend some Subway meetings together but led their personal lives largely independent of each other. Two sources told Insider that at company conventions, DeLuca pursued franchisees' wives. One said that DeLuca felt entitled to "approach any woman because he was responsible for their husband's success in stores." While his attitude infuriated some, others saw him as a "demigod" and looked the other way.

"If you wore a skirt and had a pulse, he would chase you," a business associate said.

Fred's daughter-in-law Ana DeLuca said that the company and his family excused his bad behavior. "Fred could do anything that Fred wanted to do and everybody would just agree," she said.

DeLuca created a shirtless calendar of Subway executives

In 2000, DeLuca created an internal boudoir calendar of male Subway executives. Representing January, DeLuca smiled while shirtless in his office with a towel flung over his shoulder. He is holding a glass of champagne and a blue notebook with a cover that says, "executive office" (via Business Insider).

On other calendar pages, chief development officer Don Fertman posed shirtless in a conference room, and marketing head Dick Pilchen stood undressed behind a shower curtain.

The former employee who shared the calendar said that the social atmosphere at Subway felt like a "bizarre" high school. Some embraced the "big family" atmosphere that DeLuca cultivated through frequent parties and at work. Others, however, felt it crossed boundaries and made them uncomfortable. They cite the calendar as just one example that showcased the lack of professionalism at the Milford, Connecticut headquarters.

Because DeLuca held all the power at the company, many employees were terrified of him. DeLuca would not hesitate to cut people out of Subway, even if they were successful. John Haynes, a franchising expert and coauthor of DeLuca's book, told Business Insider, "He knew he created a system that people behaved out of fear."

DeLuca secretly adopted a child

DeLuca's daughter-in-law said that Cindy Mattson, a long-term girlfriend, told her in 2012 that she and DeLuca had adopted a child together. While DeLuca did not sign the adoption papers, they had named the child Luca in honor of the Subway co-founder's last name.

After DeLuca's death, Mattson filed a lawsuit against his estate claiming that he had promised to support her and her son with $20 million. DeLuca's next of kin, son Jonathan and widow Elisabeth, initially denied the claims. While neither Mattson nor the estate responded to media requests, in 2016, Mattson filed a document stating she had received full payment or otherwise settled the claim.

"No one ever understood why [Elisabeth] never divorced [Fred]," a long-time franchisee said. "It never made any sense. She was entitled to billions of dollars, but he had this reign of terror over her, over his son [Jonathan]."

Jonathan DeLuca now sits on Subway's board of directors, but his father "never had any confidence in Jonathan," a business associate said. Two sources said that Fred refused to pay for his son's college education, so Jonathan graduated from the University of Michigan in 1994 on a scholarship.

DeLuca was accused of defrauding franchisees

Chains like McDonald's and Burger King have many franchises operated by investment firms. By contrast, most Subway owners are individuals and families, and many of them are immigrants without English proficiency.

With an "anywhere and everywhere" mentality, Subway opened restaurants in gas stations and convenience stores, at truck stops, and in rest areas. Franchisees complained that restaurants were opening within blocks of each other, making it difficult to succeed.

Subway's vast network of stores is organized into regions overseen by a development agent. This agent is responsible for recruiting new franchisees, approving buyers for existing stores, and for monthly store inspections. But most Subway development agents are also franchisees, setting up what many see as a conflict of interest. Development agents have both the means and incentives to shutter competing stores and take over profitable ones.

Responding to allegations of abuses in Subway business operations, DeLuca said in 1998, "I really feel terrific that so many people have done so well. But there are risks. People can lose money. It bothers me that people lose money, but I don't lose sleep over it. This is America."

DeLuca and his co-founder didn't have a lot in common

According to a business associate, when Subway first opened its Connecticut headquarters, Peter Buck asked where his office would be. DeLuca told him he didn't get one, and even decades later, he never did. If anyone asked Buck a question related to Subway, his stock answer was "talk to Fred."

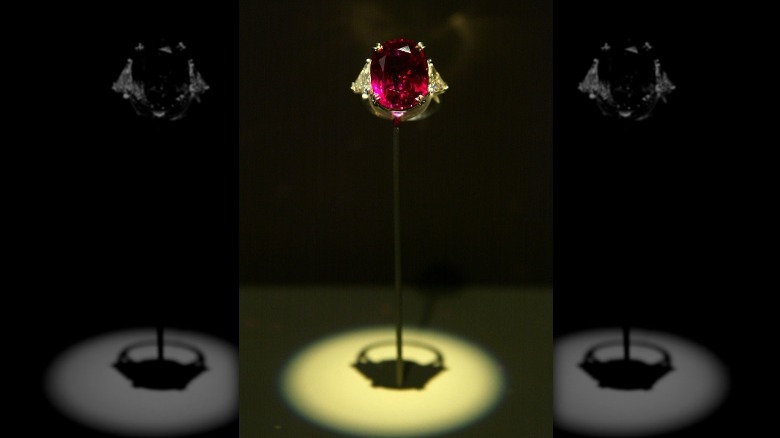

Buck seemed happy to sit back and reap the profits from his share of Subway, which Forbes estimates to be $1.7 billion. Buck focused his attention on philanthropy, including his namesake Peter and Carmen Lucia Buck Foundation. In 2004, Buck endowed the Smithsonian the funds to buy a rare 23.1-carat ruby. The gem is now known as the Carmen Lucia ruby to honor Buck's late wife.

Because Subway remains a privately held company, DeLuca and Buck did not have to disclose much financial information. This opacity has been a hallmark of Subway since its inception. Executives kept a low profile, frequently declining media interviews. In 2010, chief development officer Don Fertman appeared in the reality show "Undercover Boss." Franchise consultant Malcolm Knapp explained to Bloomberg in 2015 that outside of the reality show appearance, "nobody knows them."

DeLuca may have been warned about Jared Fogle

In 1999, Men's Health featured Jared Fogle in an article titled "Stupid Diets That Work" (via Los Angeles Times). The article led to Jared becoming the omnipresent Subway spokesman for 15 years. According to Business Insider, DeLuca was not particularly close to Fogle, and, according to one associate, found him annoying, especially as he began demanding more money.

In 2015, the FBI and state authorities raided Fogle's home. Within hours of the raid, Subway cut ties with him, claiming to be "shocked about the news." Fogle was arrested one month after DeLuca's death, ultimately admitting to child pornography and traveling to engage in sex with minors. According to former franchisee Cindy Mills, Subway knew about Fogle's sexual abuse of minors as early as 2008. Mills and Fogle met at a Subway event and had an affair, during which he told her about sex with underage prostitutes. She also said Fogle wanted her to set up a meeting with her underage cousin.

Mills' claims may not have been Subway's only tip. According to a 2007 exclusive, while Fogle was a college student (and when first profiled by Men's Health), he ran a black-market pornography rental service. His "Subway diet" began mostly because a store opened on the first floor of his dormitory — no doubt a result of DeLuca's ambitious location expansion plans.

DeLuca left no real plan for succession

During Subway's decades of exponential growth, DeLuca remained obsessively hands-on. Buck, who retained roughly 50% ownership, took the opposite approach, enjoying a quiet billionaire life and apparently satisfied to remain a silent partner.

DeLuca was diagnosed with leukemia in 2013. DeLuca appointed his sister Suzanne Greco to run operations, reporting directly to him. He was careful not to call Greco his successor. Don Fertman, Subway's chief development officer, said at the time, "He's not acknowledging a health issue. Not to say he doesn't have one. He's engaged and hands-on. He is still CEO." Greco's promotion wasn't publicized until Bloomberg News reported it.

According to three sources who spoke to Daily Post LA, DeLuca either couldn't comprehend the idea of Subway going on without him upon his death or simply refused to believe it was possible. Shortly after his death, Greco was named CEO but struggled and was ousted in 2018.

According to Business Insider, a number of former executives and franchisees believe Subway can only be saved by shedding its DeLuca baggage. Industry sources told The New York Post that the coronavirus pandemic is the only reason the company wasn't auctioned in 2020 as initially planned. Buck died in 2021 at the age of 90.