27 Delicious Cuban Foods You Need To Eat At Least Once In Your Lifetime

With travel to Cuba for tourism restricted by the U.S. government, it might seem hard to experience what life on the island is like (via the U.S. Department of State). However, there's one easy way to make yourself feel like you're traveling to Cuba without leaving your hometown, and that's by eating Cuban food.

Cuba is well-known as the birthplace of famous cocktails like the daiquiri, but its cuisine is just as interesting and tasty as its mixology. If you happen to live in a hub for Cuban-Americans like South Florida, you probably already know this, but it's not super easy to find Cuban restaurants in some parts of the U.S. Fortunately, you can make many different Cuban recipes using only ingredients that are available in an average American grocery store. Whether dining at a Cuban restaurant or cooking at home, these are 27 Cuban foods you definitely need to try.

Ropa vieja

Ropa vieja, the Spanish translation of "old clothes," tastes a heck of a lot better than the thing it's named after. Although it's unclear exactly how it got its name (one legend says the first ropa vieja actually magically transformed from old clothes into delicious food), it most likely started as a way for Spanish Jews to get around the religious prohibition against cooking on the Sabbath. Since ropa vieja can be cooked ahead of time and eaten later, Jews could prepare it on the day before the Sabbath and have it ready when they needed it.

While the dish's roots may be Spanish, it's quintessentially Cuban these days. It's quite popular in Cuban restaurants stateside too, winning over diners with its deep, nuanced flavor. Ropa vieja isn't made with clothes at all (shocker), but instead tough cuts of beef that get braised in a seasoned tomato-based broth until they become tender enough to fall apart. Our recipe seasons the braising liquid with, among other things, white wine, celery, carrot, oregano, cumin, and a hefty dose of garlic. Vinegar and olives add a little acidity and brininess to cut through all the hefty, savory flavors.

Croquetas

Croqueta (or croquette) is a term that can refer to basically any kind of food (often leftovers) that is shaped into a log or a ball, breaded, and deep-fried. It's a great way to repurpose leftovers into something that tastes delicious, and versions of croquettes can be found in cuisines from across the globe. Cuban croquetas come with a variety of different fillings, but perhaps the most classic is ham (jamón).

Per A Sassy Spoon, to make croquetas de jamón, you first prepare a very thick milk-based white sauce thickened with roux. Season it with white wine and a little nutmeg, and then fold in ground or finely diced ham. This mixture needs to cool so it's firm enough to hold its shape. Once set, you can roll it into finger-shaped pieces, bread the pieces in breadcrumbs or crushed crackers, and fry. It's a fairly labor-intensive process, so if you're lucky enough to live close to a Cuban restaurant, you might want to let them make croquetas for you rather than doing it at home. That said, they are quite delicious, so you won't regret going to the trouble of making them yourself if you have to.

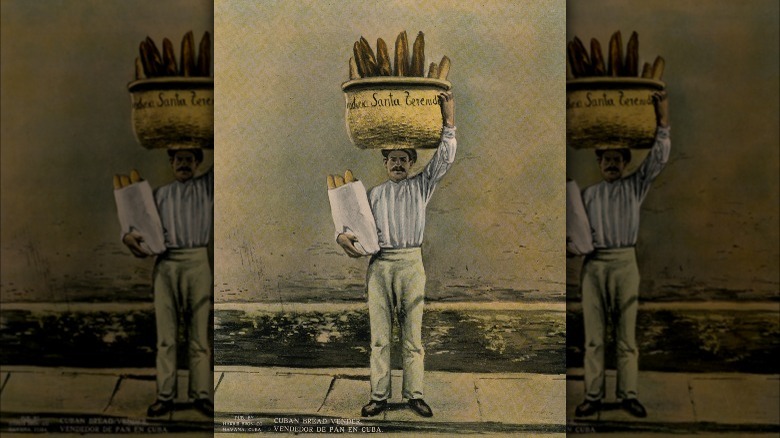

Pan Cubano

Cuban bread, or pan Cubano, is synonymous with the cuisine of the Cuban diaspora in America, but it's not clear if its origins are actually Cuban at all. According to The Guardian, the first person who made pan Cubano in the U.S. was Juan Moré, who opened a bakery in Ybor City, Florida in 1915. He began baking long loaves of bread somewhat similar in shape to hoagie rolls or French baguettes. This bread became popular with the city's cigar factory laborers, many of whom were Cuban. Juan himself had been born in Spain, but moved to Cuba as a soldier in the Spanish-American War before finally settling in Ybor City. The Moré family claims that Juan stumbled upon the loaf of bread that inspired pan Cubano while he was living in Cuba, but the story is hard to verify.

No matter where the bread came from, it's undeniably great. It's the foundation to any proper Cuban sandwich, but it's also perfect on its own, served warm on the side of any Cuban meal (via Tampa Bay Times). It's quite similar to Italian or French bread, but with one crucial addition to the dough: lard. Per Allrecipes, the lard, as well as some special cooking techniques, set this recipe apart from other types of white bread. The lard might be the secret behind its yummy flavor and its unique fluffy on the inside, crispy on the outside texture.

Cuban sandwich

Speaking of Cuban sandwiches, the island's cooks have produced several worthy additions to the sandwich canon, but only one gets to be known simply as the Cuban sandwich: roast pork, ham, Swiss cheese, pickles, and mustard on a perfectly-griddled, crispy piece of pan Cubano. It's a formula that should never be messed with, unless you're in Tampa, in which case, it's traditional to add Genoa salami to the mix (and they should know how to make a proper Cubano, since Thrillist notes that the modern form of this sandwich probably got its start in Tampa).

Although Miami also claims to have invented the sandwich, it's more likely to have originated, like Cuban bread, in Tampa's Ybor City neighborhood. That explains the presence of salami in Tampa's version, as some of the neighborhood's cigar workers hailed from Italy. Either way, Thrillist writes that Cuban immigrants were probably just making a version of a sandwich they already made in their home country, though historical evidence for this claim is scant. No matter who actually invented it, however, the Cuban sandwich is one of the tastiest things you can eat between two slices of bread.

Frita Cubana

Cuba's (and South Florida's Cuban-American community's) other great contribution to the world of sandwiches is the frita, also known as a Cuban burger. According to Burger Beast, the frita was originally a street snack that debuted in Cuba in the 1920s. Friteros would sell the diminutive sandwiches, which consisted of small chorizo-spiced beef and pork patties slathered with tomato paste or ketchup and topped with diced onions and fried julienned potato sticks, to passersby on the sidewalk.

Like many Cuban specialties, the frita found its way to U.S. shores, changing slightly after it came to America. Instead of being a street food, fritas in America are generally sold at Cuban cafes. Rather than using cut-up pieces of Cuban bread as buns, as was popular in Cuba, American fritas are served on typical burger buns, or more commonly, Cuban rolls. Fritas are most easy to find in Miami's Little Havana neighborhood, but sadly, the small cafes that serve them aren't as commonplace as they used to be.

Yuca con mojo

Yuca, also known as cassava or manioc, is a bland, starchy root vegetable that's a very popular carbohydrate-rich food in tropical regions of the world (via My Dominican Kitchen). In the U.S., yuca is perhaps most commonly-consumed in its powdered form, known as tapioca. You'll find tapioca starch in puddings, in gluten-free baked goods, and in the boba balls that are added to milk tea. Exclusively eating cassava in dried, powdered form does it a disservice, however, as it's also a tasty vegetable in its own right. It's quite similar to a potato, but with a unique, mildly nutty flavor and a fibrous texture.

Like potatoes, yuca needs some assistance in the flavor department to cut through all the starch. It's a blank canvas for whatever seasoning you want to use with it. One classic Cuban preparation for this vegetable is yuca con mojo, which is boiled yuca in a zesty garlic-citrus sauce. The Spruce Eats suggests smothering chunks of tender yuca with olive oil, orange juice, lime juice, cumin, oregano, and a ton of garlic. The acidity and sharpness of the mojo sauce wakes up the yuca and turns it into a perfect side dish for a variety of foods.

Batidos

Per Toot Sweet, batido is a blended drink with milk and ice that's often flavored with tropical fruit. You can think of batidos as being somewhere between smoothies and milkshakes. A classic Cuban flavor of batido swaps out the typical fruit with puffed wheat cereal. Batido de trigo, as it's called, definitely leans more toward the milkshake side of the batido spectrum than the smoothie side. This recipe from A Sassy Spoon enriches the mixture of milk, puffed wheat, and ice with sweetened condensed milk and a decent amount of sugar to make a creamy liquid dessert.

While the idea of a milkshake flavored with grains might seem novel to you, if you've ever had a malted milkshake, you've had something similar. A classic diner malt gets its flavor from malted milk powder, which is a combination of dried milk, wheat, and malted barley. The grains add a pleasantly toasty, nutty flavor to the final product.

Empanadas

Empanadas show up in Latin American cuisines from many different countries. We have a recipe for Argentine empanadas if you want to try that region's version of the popular snack. According to Culture Trip, empanadas probably came to the New World with Spanish settlers. The original version was more like an American double-crust pie that was sliced into individual portions, but it developed into the handheld, self-contained empanada we know now as it spread across the Americas.

Typical Cuban empanadas are savory pocket pies filled with picadillo, a seasoned ground beef mixture. Beyond those specifications, the individual recipes can vary. This one from Food52 uses a relatively simple picadillo recipe but adds flavor by deep-frying the pies. Another recipe from the Cooking Channel calls for the empanadas to be baked, which is simpler for home cooks to accomplish. However, the Cooking Channel's picadillo filling is much more complex than the other recipe's is, calling for white wine, capers, olives, and raisins to be mixed with the beef.

Flan

Flan is another pan-Latin American dish, but as with empanadas, Cuba puts its own spin on the formula. Also like empanadas, flan began as a Spanish dish; in this case, the caramel egg custard was invented by nuns in medieval Spain (via Eater).

Cuba's flan tradition is defined by the difficulty of sourcing fresh ingredients on the island. While flan is made with fresh milk in many parts of the world, in Cuba it's usually prepared with canned evaporated milk and sweetened condensed milk. The canned milks are cheaper than fresh, and they also make Cuban flan richer and creamier than flan made with fresh dairy. The lack of ovens in many Cuban home kitchens has led cooks there to use imaginative methods to cook their custard. Cookbook author Megan Fawn Schlow told Eater that "Today, you'll find people making individual flans at home in empty soda cans that have been cut in half because that's what they have. And because many home kitchens don't have ovens, a lot of people make their flan in a bain-marie on the stovetop."

Bistec de palomilla

Bistec de palomilla is a flavorful preparation for thin cuts of sirloin steak (via Hispanic Food Network). As we've noted, sirloin steak can be a little tougher than other types of steak, but bistec de palomilla gets around this potential issue by using an acidic marinade and cooking for a short amount of time, much like the procedure for a London broil.

Hispanic Food Network's palomilla recipe shows that mojo sauce isn't just for yuca, as it's used here to marinate the steak and then deglaze the pan after searing. The mojo's assertive combination of citrus juice, garlic, oregano, and cilantro adds a ton of flavor to the steak. It then turns into a lovely pan sauce that gets poured over the steak after cooking in a skillet with some sliced onions. You can serve bistec de palomilla with any accompaniments you like, but we heartily endorse black beans, white rice, and fried sweet plantains.

Picadillo

We mentioned picadillo briefly while we were talking about empanadas above, but it's important enough to get its own entry. While you frequently see it as a stuffing for empanadas and for the papas rellenas you'll read about below, it's also common to find it served as a standalone entree next to a pile of fluffy white rice (via Serious Eats).

Good picadillo starts with sofrito, a mixture of finely chopped onion, pepper, tomato, and garlic that gets sauteed gently to allow the vegetables to soften and develop their flavors. The sofrito acts as the base of the dish, lending savoriness to the ground meat, which is often beef but can also be pork or a blend of the two. Picadillo is all about layering flavor, with wine, green olives, cumin, oregano, capers, and raisins all adding interest and variety to the hash. Serious Eats also puts potatoes in their picadillo recipe, though they write that you can omit the spuds without harming the end result.

Moros y cristianos

The name of moros y cristianos (Moors and Christians) comes from Spanish history. According to National Geographic, for a time, predominantly-Christian Spain was ruled by a group of people from North Africa who were referred to as Moors. This period is the inspiration for the dish's name, as it is a combination of white rice and black beans (via Recetacubana).

Now that the history lesson is done, we can move on to the actual dish. At its heart, moros y cristianos is a humble dish of rice and beans. The rice is cooked in the same liquid as the black beans, so it gets stained a brownish-purplish color. The thing that makes this dish special is the depth of flavor that comes from the seasonings. Recetacubana's version uses pork (either bacon or chicharrones), bay leaf, cumin, onion, and garlic to add richness and savoriness to the beans and rice. Cooking the beans from dry makes this taste so much more special than simply cracking open a can of black beans and mixing it with rice.

Tres leches cake

Tres leches cake shows up in different forms throughout Latin America. It's generally a sponge cake that's soaked in three types of milk and then topped with some kind of frosting or garnish. Our version uses heavy cream, evaporated milk, and sweetened condensed milk for its three dairy ingredients, and tops the cake with whipped cream and sliced strawberries. The Cuban tres leches recipe shared by Three Guys From Miami is a little bit more complex and indulgent.

The first Cuban twist is in the soaking liquid, which gets a shot of rum in addition to the three milks. The frosting of this version is much more complicated than simple whipped cream, requiring you to cook a syrup to a precise 230 F and pour it into stiffly beaten egg whites. Instead of strawberries, it's garnished with a maraschino cherry. Three Guys From Miami also notes that Cuban restaurants in Miami often one-up tres leches by serving quatro leches cake, which is just tres leches topped with dulce de leche, a milk-based caramel.

Papas rellenas

Papas rellenas are another delicious use for picadillo. In this case, the picadillo gets stuffed into little balls of mashed potato, coated with breadcrumbs, and then deep-fried (via Taste of Home). It's a symphony of flavors and textures, with the crunchy coating yielding to reveal a creamy, starchy potato interior encasing wonderfully sweet-savory-salty Cuban picadillo.

Papas rellenas are an idea too good to be confined to one country, so you'll find them in other places as well. The Colombian version from My Colombian Recipes omits the bread crumbs on the outside. The picadillo is also different, as it doesn't contain the raisins that sweeten the Cuban version, instead leaning into savory flavors with sazon and scallions. Kitchen Gidget's recipe for Puerto Rican papas rellenas also leaves out the bread crumbs and uses Puerto Rican picadillo, which is based on a completely different type of sofrito than Cuban picadillo. Puerto Rican sofrito has no tomatoes, substituting them with fresh herbs (via Kitchen Gidget).

Pudín de pan

Pudín de pan just means bread pudding, and we probably don't need to explain to you what bread pudding is. However, Cuban bread pudding is special, and it's quite different from the kind you'll find in most American restaurants. While classic American bread pudding tends to have a chunky texture with identifiable pieces of bread sitting in cooked custard, the pictures of pudín de pan at Cuban Food Market and Cooking in Cuban show that it has a much more uniform texture, with the soaked bread totally dissolved into the mix. Cuban bread pudding recipes also include almond extract, white wine, toasted almonds, cinnamon, and nutmeg.

Perhaps the most unique part of Cuban bread pudding is that it's cooked on top of a layer of caramel, much in the same way as flan. You make the caramel by melting sugar in a skillet, then you pour it inside the baking dish (carefully, since melted sugar is ripping hot). Then you add the bread pudding mix on top and bake the whole thing together.

Vaca frita

Vaca frita (fried cow) breaks all the normal rules for cooking steak (via Food52). Instead of searing your piece of beef until it just reaches medium rare, you take a piece of flank steak and boil it for half an hour until it's gray, cooked through, and unappetizing. Then, you shred this desiccated beef and put the shreds in an aggressively acidic and garlicky marinade. Finally, you fry the beef shreds with onions until they caramelize and become crispy around the edges.

Although it seems like a recipe that shouldn't work, it really does. Somehow, after being boiled, shredded, bathed in acid, and fried, the beef ends up pleasantly tender. It's also seasoned to the core from its time in the marinade. Watching somebody cook vaca frita might make a French chef cry, but the dish is a great example of the truth that there are many ways to turn a specific ingredient into something delicious. Just because a cooking technique seems strange to you, it doesn't mean that it's not worthwhile.

Pulpeta

You might think of meatloaf as the epitome of Midwestern American food, and you wouldn't be wrong. However, plenty of other cultures know that mixing ground meat with fillers and flavorful mix-ins to stretch it out is a good idea, and Cuba is no exception. However, the Cuban version of meatloaf, pulpeta, is pretty different from anything you'd find at a typical American diner.

For one, pulpeta is traditionally stuffed with hard-boiled eggs, which gives the dish an interesting cyclopean look, with an eggy eye staring out of every slice (via Hispanic Food Network). The composition of the meatloaf itself is also different, with ground ham enlivening the ground pork and beef and a hefty dose of Spanish paprika adding some nice smoky goodness. Perhaps the most drastic deviation from American meatloaf is that pulpeta is not baked. Rather, the loaf is seared and then braised in a seasoned tomato sauce. This is a delicate process, as the pulpeta can break apart if you're not careful, but it results in a moist, highly-seasoned meatloaf.

Plantains

Plantains, the starchier, firmer relative of the banana that's usually eaten cooked, are very popular in Cuban cuisine. There are as many ways to cook plantains as there are stars in the sky, but frying them is one of the tastiest ways to prepare them (as is true for so many ingredients).

There are two main ways to prepare fried plantains, and they produce very different results. The reason for this is that one uses starchy, unripe green plantains, while the other uses sweet ripe ones. The former version, tostones, is made by frying slices of green plantain twice (via Three Guys From Miami). After the first fry, the plantain slices become soft, which allows you to smash them into thin disks. The second fry crisps them up, turning them into crunchy chips.

Per Bon Appétit, fried sweet plantains, known as maduros, only need to be fried once. The plantain pieces become quite dark on the outside during cooking, and the inside becomes creamy and candy-sweet. You can season them with salt or granulated sugar (or both) after they come out of the pan.

Arroz con pollo

Chicken and rice is one of those combinations that soothes you on a deep, primal level, and Cuban arroz con pollo is comfort food at its finest. Per Que Rica Vida, it's best made with dark meat, skin-on chicken, either thighs or legs. That's because arroz con pollo cooks for a relatively long time, which dark meat can handle better. That's not to mention all the delicious chicken fat you get from the skin, which will certainly make the dish tastier.

Like other Cuban dishes we've covered, the flavor base for arroz con pollo is a sofrito of peppers, onions, and garlic. The veggies are sautéed in a mixture of olive oil and chicken fat, then the chicken, veggies, and rice are all simmered together in a mixture of tomato sauce and chicken stock until the rice is tender. The rice gets its beautiful golden color from the addition of Bijol, a condiment made out of cumin, corn flour, annatto, and food coloring.

Tamales

You're probably familiar with Mexican tamales, and from the outside, Cuban tamales look very similar. Peel back the corn husk, however, and you'll find a very different food within. Perhaps the most important difference between Cuban tamales and their Mexican cousins is the type of corn used to make the dough. Mexican tamales use masa harina, a special kind of dried ground cornmeal that has been treated with lime. The Cuban version, on the other hand, uses fresh corn that is removed from the cob and ground into a paste. You can't just use regular corn on the cob from the grocery store, however; according to Just A Pinch, you need to find maiz criollo, which is less sweet than the corn you boil and serve with butter in the summertime. Although maiz criollo isn't widely available in stores in the U.S. outside of Florida, it's easy enough to buy on Amazon.

The other thing that sets Cuban tamales apart is how they're put together. Instead of wrapping the corn dough around the filling, you mix it with the meat and vegetables so the fillings are evenly distributed throughout the whole tamale.

Chiviricos

It's hard to go wrong with fried dough covered in sugar. From funnel cake to donuts to beignets, the combination of fat, starch, and sweetness always hits the spot. One of Cuba's local variations on this formula is called chiviricos. According to Recipes of Cuba, these thin, crispy leaves of sugar-dusted fried dough are a popular snack and can be eaten alone or used as a vehicle for sauces or dips. Their recipe for the treat calls for you to make a volcano-shaped mound of flour on a table and put your liquid ingredients into the crater in the middle of your flour mound before mixing, much like the traditional method for making fresh pasta (via Epicurious). Once your dough comes together, you roll it out thin, cut it into pieces, and fry it.

If that sounds like a lot of work for a snack, don't worry: You can buy bagged chiviricos online from places like Cuban Food Market. They might not be quite as good as the homemade kind, but you won't mess up your whole kitchen as you likely would deep-frying at home.

Pastelitos

We would be remiss if we didn't include the pride and joy of Cuban bakeries everywhere: pastelitos. Per The New York Times, pastries are very popular both in Cuba and in parts of the U.S. with a significant Cuban population. While bakeries make a variety of different sweet treats, pastelitos are the most popular type of Cuban pastry. They can come stuffed with many kinds of fillings, including savory meat-based ones, but the most iconic variety is made with guava paste and cream cheese. According to The Kitchn, guava paste is a thick blend of guava, sugar, and pectin. Rather than being spreadable like jam, it's more of a sturdy gel that can be cut into slices. The flavor of guava itself is hard to describe, but we've previously compared it to strawberries and pears.

If you don't live near a Cuban bakery, you can always pick up some guava paste online and make pastelitos at home. The New York Times recipe uses pre-made frozen puff pastry so you don't have to go through the laborious process of making pastry dough from scratch.

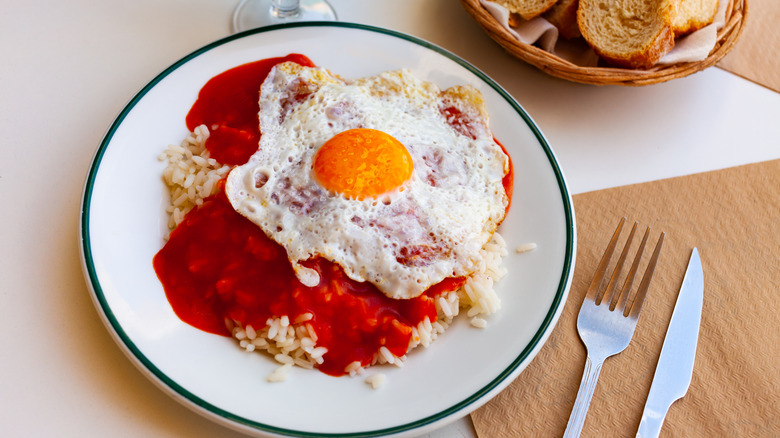

Arroz a la Cubana

Arroz a la Cubana (or as they call it in Cuba, huevo frito con arroz), is a simple and easy breakfast dish that, at its most basic, is just rice with a sunny-side-up fried egg (via Hispanic Kitchen). The touch that gives this dish its Cuban flair is that it's topped with sofrito, the mix of tomatoes, peppers, onions, and garlic that we've mentioned several times in this list. In this case, rather than being cooked as the base of the dish, the sofrito is more like a runny tomato sauce.

The formula of rice plus fried egg is a popular one that has earned global fans. A version of arroz a la Cubana is a popular breakfast in the Philippines, according to Panlasang Pinoy. The Filipino version is more elaborate, pairing the rice and egg with fried bananas and a ground meat hash that bears more than a passing resemblance to Cuban picadillo.

Sopa de pollo

We all know what chicken noodle soup is, right? It comes in concentrated form in a red-and-white can made by some people named Campbell. We're not here to cast aspersions on Camden, New Jersey's greatest contribution to food (Campbell's Chicken Noodle topped our list of the best canned soups, after all), but the combination of poultry and pasta can be so much more interesting than anything that comes in a can.

Since it's a home-cooking dish, there are as many recipes for Cuban chicken noodle soup (sopa de pollo) as there are abuelas. This recipe from For The Love Of Sazón gives you a pretty good idea of what to expect, however. The broth gets jazzed up with tomato sauce, spices, and (of course) sofrito, and the chicken is tender, juicy dark meat. This soup is packed with veggies, including corn on the cob, pumpkin, yuca, and potatoes. The veggies are left in huge pieces, which should provide some nice textural variation in the soup. Instead of spaghetti or vermicelli, this recipe calls for fideo noodles, which you should be able to find in many supermarkets.

Cucuruchos

While many of the items on this list are relatively easy to get your hands on in at least some parts of the U.S., you'll probably have to travel to Cuba to taste cucuruchos. The name, which translates to cone, is apt, as cucuruchos are little cones folded out of palm leaves (via Best Cuba Guide). The cones are stuffed with a variety of sweet fillings, usually coconut and sugar plus other tropical fruits like guava.

Even within Cuba, these are a regional delicacy and they're not especially widespread — they're from the area around the city of Baracoa. You can find street stalls selling cucuruchos in the rural areas near the city, but Best Cuba Guide says that they're hard to find within the city itself, as they have been supplanted by more modern snacks. If you do manage to snag one, it'll be very cheap: the going rate for a cucurucho is around 20 cents.

Churros

Churros may be a favorite snack for people at the Disney parks, but the House of Mouse certainly didn't come up with the idea. That said, the recipe for Cuban churros from A Sassy Spoon looks very similar to our Disney churro copycat recipe. Both start with making a dough that's very similar to the choux paste you would use for cream puffs. It's a little finicky; you have to bring the liquid ingredients to a boil, beat in the flour, and then add eggs one at a time until everything comes together. Then you have to load that dough into a piping bag with a star tip so you get the iconic churro ruffles when you fry it.

To eat churros Cuban style, you need to dip them into Spanish hot chocolate that's so thick that it's more of a sauce than a beverage. A Sassy Spoon also suggests dulce de leche for dipping, which sounds mighty fine to us.

Buñuelos

We're ending on one more recipe for sweet fried dough. Cuban buñuelos look kind of like donuts, but their unassuming exterior hides an interesting preparation method. Instead of using a typical donut batter, the dough is made from mashed starchy vegetables. One recipe from Petite Gourmets uses all yuca, while another from Café Bustelo uses a complex mix of yuca, sweet potato, pumpkin, and taro root. The Bustelo version is also seasoned with anise and fennel. Once the dough is mixed, it gets formed into shape, deep-fried, and then glazed with syrup.

The exact composition of the syrup is up to your taste. The Bustelo recipe doubles down on the anise and fennel, also adding guava paste and lime juice. If you're not a big fan of anise's licorice-y kick, you might prefer the relatively simple syrup recommended by Petite Gourmets, which is flavored with cinnamon and vanilla. Either way, your homemade buñuelos will be both tasty and festive.