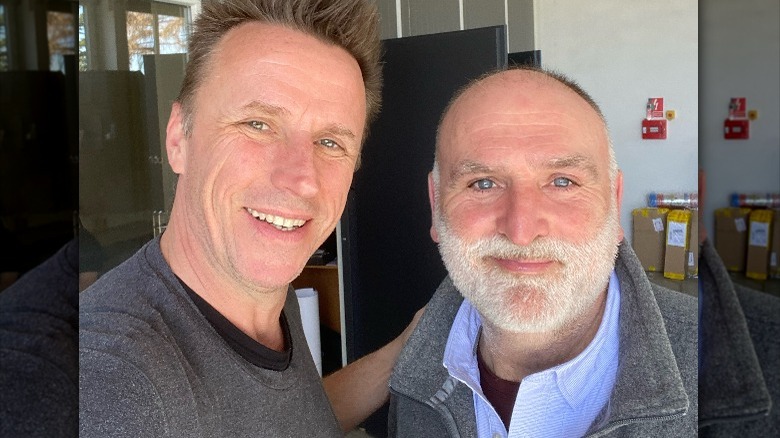

Marc Murphy Trades Chopped For Volunteering At The World Central Kitchen - Exclusive Interview

"Chopped" judge Marc Murphy didn't have any expectations when he got on a plane to Poland to volunteer with World Central Kitchen near the Ukrainian border. Every time he leaves his Airbnb, he takes everything he needs to leave for good. "We don't know the situation," he told Mashed. "We don't know if things could go certain ways."

Days are long for Murphy, who gets up at 5:30 a.m. and tries to fit in a healthy breakfast before reporting to the warehouse space-turned emergency kitchen. By the time he gets there, the early shift has already been at work for a couple of hours. Murphy is used to the grind. That's life for any chef, but this grind also takes a massive emotional toll. World Central Kitchen prepares stews in giant paella pans for thousands of Ukrainian refugees each day on a scale that's difficult to conceive in your mind. According to the organization — founded by Spanish celebrity chef José Andrés –, their main kitchen in Poland has the capability of making up to 100,000 meals daily. As of March 13, it had already served 1 million meals to refugees over 330 distribution points.

Murphy says that many of the refugees he sees, mostly women and children, are coming in for meals after weathering impossibly long lines at the border in the snow and cold. They're fleeing bombs and on their way to anywhere that will take them. In this exclusive interview with Mashed, Murphy describes his day-to-day on the ground, and why the work World Central Kitchen is doing is so crucial.

Marc Murphy describes his day cooking for refugees

I think the real question is how are you?

I'm good. I'm working a lot. I'm cooking a lot of food. I actually rented an Airbnb, but I'm about an hour out of where the World Central Kitchen main kitchen is. I've been commuting. If I stay much longer, I'm going to definitely try to look for a place a little closer.

Take us through your day-to-day. What does it look like?

I get up around 5:30 in the morning. I try to have a little healthy breakfast, because when you're working hard like this — working long hours — the one thing I know, from my experience, is you got to make sure you take care of yourself or else you're going to go down in flames at some point, being over-tired and get[ing] sick. I try to have a little healthy breakfast. I get myself ready. I don't bring everything with me, but I bring everything that I need with me so that I could actually just leave if I had to. I have my clothes and stuff here, in the Airbnb, but we don't know the situation, we don't know if things could go certain ways.

I have my backpack, I have extra clothes. I have bars with me in case we all have to head out and not be able to come back here. That is a little strange, to leave a place where you're sleeping and staying and being like, "Well, I have everything with me. I don't have to come back if I have to," and then I drive to work [for] about an hour and 20 minutes.

Marc Murphy describes making stews for 1,500 people

What happens after you get to work?

I get there and usually I jump right in. The chefs that are there earlier get there around 6:00 because we have to get food out the door by 8:30 for the first run. The stews are all ... Everything's pretty much prepped the night before. We get everything ready so they all [have] to be reheated. Sometimes we need to have broths made because if it's cold, they want hot broth at the border because it's cold and they want to keep warm. They're standing in line for hours.

We then have managers at each post. There's a couple [of] different border crossings, there's train stations. There's also some refugee transfer centers, where people are actually living, some longer-term, some are there for a night or two. They're basically old malls [where] they've put these cots everywhere, and [there are] no more stores.

We cook all day. We have these huge cauldrons that we cook in, we can do stews for about 1,500 people in each one of them. We also have these steam ovens that steam and roast, so we try to roast a lot of the meats in there first to break them down, and then chop them up and cut them up and then make the stews.

We're trying to keep pretty consistent with flavors from here. We're using beets, we're using horseradish, we're trying to go with their pallet. Nothing too spicy. They don't eat much spice out here, it seems. Oddly enough, I went to the store and I was questioning because I can't find vinegar. Vinegar is something that they don't seem to use much in Poland.

Then I drive home, and then sometimes I'm doing things like this [talking to the press]. Then I'll cook myself a little dinner, and have a couple glasses of wine, and do it all over again the next day.

Can you take me on a tour of the kitchen, in your mind? What are your most important tools? What's the layout? What's different about this that we might not imagine?

When World Central Kitchen found this — it's basically a big warehouse space. I think it was supposed to be a winery that never happened because of COVID. They got this space. It's basically a large warehouse with a huge garage door — two of them, one on one side and one on the front. You walk in the front, this is where the loading happens. The trucks that deliver the food back up, and there's a person there, a logistics person, that's getting orders. They want 1,500 meals of [this], they want 500 meals of [that]. Then we do it three or four, sometimes five times a day, the deliveries go out. Some of the deliveries will take a long time, because one of the border crossings we're supplying is two hours north, so we have to drive it up there.

World Central Kitchen's 'amazing' scale

Describe the scale of this to us.

You walk in the kitchen, there's some offices on the left because you can imagine the logistics you need. There's a purchaser, there's a facilities person that's making sure everything's working properly. Then, on the right side [is] where the pallets land, where, let's say, we'll get a tractor-trailer full of apples. In the back, we have pallets of all the dry goods, like the salt, and the beans, and the pasta, and the rice, and things like that. In between those, there's another big garage door, where the forklifts come in and out and load up and unload things.

This facility is getting a lot of deliveries. They're buying a lot of deliveries, and then a truck will pull in, it's going to be going into Ukraine. What they do — I don't have anything to do with this — but they'll load that truck up. It's going to a specific area. Basically, if you can imagine, we'll get a truckload of rice, they bring it in, and then they're going to reload up a truck that's going to go to Ukraine. It's going to have some rice, some chicken, some oil, some frozen vegetables, and then that truck goes.

We're not just cooking there; sometimes, some of the pallets have written on them, "Do not use, this is going to Ukraine." We'll know where things are being distributed. Then, in the back, also, on the left, there's a ginormous walk-in. The day that I got here, which was over two weeks ago, they just got this space. They basically built it out in five days. The walk-in was half-built when I got here, they were literally putting the walls up and putting the compressors in. It took two days to get it going, so now, we have a huge walk-in.

Have you ever cooked on this scale before, for so many people?

I've done large cooking, but no, this is pretty consistently large. This is quite amazing, yeah.

What a meal means for refugees

This is different than your standard commercial kitchen.

We have a lot of prep tables where we put all of the volunteers that are here to peel potatoes, to chop peppers, to cut zucchini, to peel and chop onions, or cabbage. There's a big area there where people are doing that with these metal tables. In the front part, we're working with six very large, what we call paella pans, where we can do stews. We can make rice in there. I can make a stew in there, like a beef stew that will feed about 1,500 people. Those are going pretty much consistently. We're either roasting off, sweating off things, or whatever vegetables, and we do a lot of sofritos because of Jose Andres [who is World Central Kitchen's founder], and we have some Spanish chefs and we make a lot of sofrito.

Along the back wall, we also have 12 of these large ovens that you put rolling racks in. Either you can do dry, you can do [a] dry steam, or just steam. For example, if you want to put a rack full of potatoes in there and steam them, which is what we're doing now, because it's easier to steam a whole thing of potatoes, and then add that to a stew instead of cooking the stew. We're trying to speed things up sometimes, because we don't know.

How has that kind of experience changed the way that you're thinking about food — or cooking? A hot meal takes on a completely different meaning in a situation like the one you're in.

Yeah, nourishing people and giving them a feeling maybe of a little dignity, and a warm belly full of food after traveling for so long. It's still cold here, and having [a meal] is really wonderful. We still have snow on the ground outside. I wake up in the morning, [and] the one thing I forgot — I scrape my windshield every morning. The dew is too thick to get through it, so you can imagine it's cold. These poor women and children, mostly, that are traveling here, coming over the border with their suitcase and a grocery bag, or some plastic bags. It's heartbreaking to see. I'm happy that my skills and what I know how to do, I'm able to at least put [my skills] to work and do something that is making [refugees] have a little bit of moment of comfort and nourishment.

Food prep for refugees is a 'moving target' according to Marc Murphy

How have you seen the situation evolve?

The numbers are changing all the time. Sometimes, the borders are busy [and] we need 1,500 meals. [Or if] the border's not very busy today, we only need 400 meals. We want to be able to be ready at a moment's notice. Even boiling water for 1,500 people, there's no moment's notice for that. It takes a while.

We have to try to find different ways. We're cooking the bulgur wheat sometimes before in the steamers, and adding that to stews. Also, sometimes some of the places that [serve refugees] ... because [the food we make] depends on their layouts, some of them actually have electric chafing dishes where they could put the rice, and then put the stew over here so they could serve it that way.

We just found out that some of the transfer centers ... because some of these [are] where the refugees are going and they're either spending the night for a night or two, or maybe a week. Then, there's buses that are designated that are going to Italy, to France, and Germany, where people can go meet up with either friends or relatives where they're going to stay. Some people don't have time to get one of these hot meals. We're starting to make sandwiches, because they want to grab a sandwich or get on a bus, because they're going.

There's a lot of different situations, and it's a learning curve, it's a moving target. We're doing everything we can to try to give these poor refugees some sustenance, some dignity, by having a meal and [making] them feel welcome, in a sense. It's very important, and the way we're doing it is pretty amazing. I'm very happy to be part of the team helping out.

The best and hardest thing about Mark Murphy's work in Poland

Talk to us about the best thing that you've experienced so far working with World Central Kitchen — something that's giving you a little bit of light amid a lot of stress –

One of the most beautiful things is actually seeing the humanity of other people that come and help. Some of these other chefs that are working with me, that are donating their time, and paying their way over here and getting a place to stay like myself, they drop everything and come and help people. It's pretty amazing that we have people like that out there. You can imagine they're all caring, great people. There's this one guy, Jamie, he's been here for almost three weeks and his girlfriend came over, and she actually works. She's a vet and she's working at the rescue center. They're now both involved. She's working at the animal rescue center, doing vet work, and he's there cooking. It's great, it's amazing.

And what's been the hardest thing for you ?

The hours of work, that's no problem. I'm a chef, I'm used to working hard. I'm used to going through the grind. I've been doing it my whole life. Missing my family, obviously, that's one of those things you do. It's actually weird because with FaceTime and all this stuff, you're almost there. Socializing after work, I'm not doing that with anybody because I have to drive so far to get to my Airbnb. I can't really go out and have a drink with anybody after work, so, that's tough.

Emotionally, the hardest thing is watching these women and children crossing the border with their suitcases, with this look in their eyes. They're void of ... They're tired, and I can't even imagine, they don't know where they're going. They don't know what they're going to do, most of these people. They're like, "They're bombing my country, what the hell?" It's amazing to see that, it's troubling.

Why Marc Murphy volunteered with World Central Kitchen

Did you have any expectations prior to hopping on a plane and getting to Poland? How might those expectations have clashed with the reality that you're living?

It was strange, because when I decided to do this, I was like, "I'm doing this, I need to do this. I have to do something, because I can't sit here and watch the news anymore." I did it purely because I wanted to help people. I'm on a TV show in America, "Chopped," for 13 years now. I have a little bit of notoriety of some sorts. I thought, "Oh, well I'll let people know what I'm doing." Well, first and foremost, I have to let people know that I wasn't going to be doing TV shows before, that I had to cancel everything, and everybody understood. They understand the world the way it is, and people need help, and I wanted to help.

I came here with no expectations. I didn't even know what kind of ... My first day going to this kitchen, I had butterflies in my stomach. I felt like going to my first day of work, it was funny. I was like, "Oh gosh, I haven't felt this way in a while." Before I left, I posted on social media, on Instagram and Facebook, I did a little montage and spoke and did a little video on my Instagram. You go to work, put your head down, you don't think about it. Twelve hours later, I got back to my Airbnb and I was making myself dinner and it was like, "Wow, that was my first day of work. That was pretty wild."

It's a lot of work. It's doing great. I'm helping out, and then I looked at my phone, and looked at my Instagram, and I was completely blown away. I did not know how ... I didn't have any expectations about other people thinking of what I was doing. I had over 1,000 comments on my Instagram, and I raised all this money. I was like, "Oh my gosh, I didn't really realize the other effect of what I did, or what I'm doing, and what other people are thinking." [There has been] so much support, and so much good will and all, from people that don't even know. It was crazy. I didn't expect that, but yeah, I could barely read the comments. I was weeping the whole time reading them. I was like, "Oh my God." I got very emotional, as I do.

What Marc Murphy wants you to know about the work he's doing

Thank you for doing what you're doing. It's very meaningful work. Are you there for a lot longer?

I'm taking it day to day. I've cleared my schedule. I don't know, it depends how much they need me still, or if there's any other things happening. Right now, it's status quo. It's also — I got here in the beginning and there was a lot of, "Yes." And then, some of the volunteers have to go back to their jobs. I want to see, maybe in another week or two, what the situation is, and see if I need to be here for much longer. I can probably stay another month if I have to. If they need me, I'll do that.

Can you tell us what you'd like us to understand about the work you're doing? What you want the readers to understand about the work you're doing right now?

I want them to understand that there's great organizations out there that are out there to help people, and it's very nice that they're there. Understand also that donating to causes that are helping [is] very important, especially when it's something like this. Where I feel I'm lucky, I have a skill that is needed here to help these people. A lot of people don't have skills that are needed. If you're a doctor, or a vet, who's coming here to help out with animal rescue — there are people that can come here and help — but a lot of people feel a little helpless.

The idea to be able to donate whatever they can, a little bit, it's important. It's important for them. It's important for their organizations as well. It's nice. We're doing everything we can to make these refugees' lives more comfortable. A little bit here, a little bit there, we can do what we're doing.

To support Marc Murphy and World Central Kitchen, head to Chef's Instagram page to donate to his fundraiser. You can also help fundraise by setting up your own fundraiser via Facebook or Instagram. It's a powerful tool and an easy way to encourage friends and family to donate to organizations like World Central Kitchen. To date, people have raised more than $50 million using Meta's apps for relief efforts for the people of Ukraine.