The World's First Celebrity Chef Isn't Who You Think

Celebrity chefs are everywhere today, and sometimes, it seems like you can't turn on the television without seeing an advertisement for a new show. But here's a question: who was the first celebrity chef?

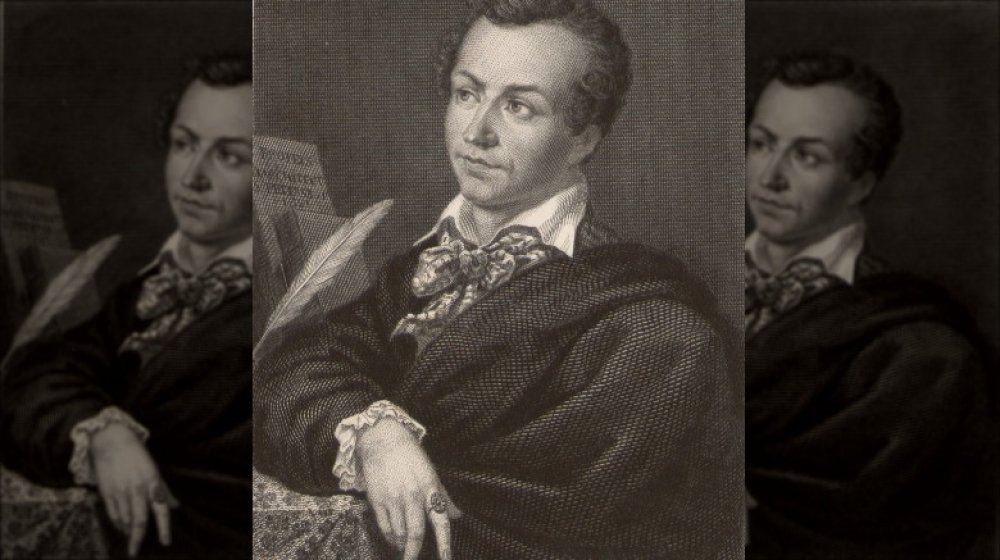

Who was the first person to mix cooking and showmanship? Who was the first to wow with their skills in the kitchen, put on display for all to see? Who first cashed in on cookbooks galore, who could demand a premium for their services, and who made those demands of some of the most powerful people in the world? Are you thinking of names like Marco Pierre White, or maybe Gordon Ramsay? Not quite — you'll have to go a little farther back to a man born in 1784.

The story of how Marie-Antoine Carême changed the way the world thought about food is an incredible one, and he's the reason cooking first became something of a spectator sport. He elevated it from a necessity into an art form, and he showed the world just how beautiful food could be. He did it all before the tricks of the television, too, and that's seriously impressive. Here's what you should know about him and the contributions he made to the culinary world.

The world's first celebrity chef came from the most unlikely of places

Marie-Antoine Carême was born in Paris, France on June 8, 1784 — and for those not up on their French history, it's worth a very, very brief lesson. That's just five years before the start of the French Revolution, when French citizens rose up after years and years of oppression to tear down the ruling class and rebuild a fairer society. It ended with the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte in 1799, and he'll become important to our story.

Carême was from an incredibly poor family. Sources vary, but say he was one of between 15 and 25 children, and in 1794 — during the revolution's bloody Reign of Terror — his father kicked him out onto the streets of the city and told him to make his own way in the world. The 10-year-old boy, starving and homeless, took his first kitchen job. He became a dishwasher and errand boy for a Parisian tavern called Fricassee de Lapin, and stayed there for the length of his six-year contract. When his time there was up, he moved on to a bakery owned by one of the most famous pastry chefs of the time, Sylvain Bailly. And that's an important move: while taverns catered to travelers and the common folk, these types of bakeries catered to the elite. It was a whole new world, and a whole new ruling class ready and waiting to appreciate new luxuries.

Marie-Antoine Carême's first commission sounds very modern

Marie-Antoine Carême, NPR says, caught on very quickly. Not only did Bailly teach his young apprentice everything he knew about baking and pastries, but he also encouraged the boy to learn how to read and write. Carême had a natural, innate talent for working in a bakery located in what had become one of the city's most fashionable neighborhoods, and around 1804 Carême was approached by a French diplomat named Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Perigord. Talleyrand was incredibly well-connected, and was the person to know. He gave Carême a challenge, to see just how worthy of advancement he was.

Talleyrand's request was one that would sound right at home in the story of any modern celebrity chef: He wanted Carême to create a full menu for his personal residence, but there was a catch. It needed to be a menu that would cover an entire year, there could be no dishes repeated, and it had to focus on local and seasonal ingredients.

Carême succeeded, and stepped into a whole new world of cooking for France's new elite classes. Only a few years later — in 1810 — he was brought to Napoleon's kitchen at Tuileries (pictured). His notoriety had grown, and he was commissioned to make the wedding cake of Napoleon and Marie-Louise of Austria.

One of Marie-Antoine Carême's trademark desserts is still made today

Every chef has their speciality, and Marie-Antoine Carême was no exception. He was working for Sylvain Bailly when his newly-discovered love of art and architecture met his love of pastry, and according to NPR, he began creating some of the world's great monuments and buildings out of pastry, marzipan, and spun sugar.

Bailly began displaying the confectionary creations in the windows of his bakery, and it was one of these masterpieces that first caught Talleyrand's eye. Carême created pastry-and-sugar models of ancient Greek ruins, of fortresses from China, Gothic towers, mosques from Turkey, and Persian pavilions. It was, perhaps, the conical shapes popular in Turkish architecture that led him to create the dessert that would remain popular (perhaps because it was more easily made by someone with not as much skill). It's still seen on the most elegant of dining tables today: the croquembouche. According to Ganache Patisserie, today's croquembouche was originally created alongside Carême's other masterpieces, and it's the one that's survived to pass out of the 19th century.

Even the first celebrity chef had to work on marketing himself

Marie-Antoine Carême truly stepped into the public eye around 1815, says The Oxford Companion to Sugar and Sweets. That's when he started headlining some massive events and military banquets staged in France's courts, including one where he masterminded a feast for 10,000 veterans. That was also the year he started publishing cookbooks, and they weren't just cookbooks, says NPR — he often included a sketch of himself as well, to make sure those he met on the street recognized him.

At the same time he was cooking for very important people, he was making very important friends, too. Betty Rothschild agreed to give him her patronage in 1820, and through her he met people like Chopin and Victor Hugo. The composer Rossini was so taken with him that he dedicated entire compositions to him, and Carême returned the favor by dedicating dishes to the composer.

Carême didn't just market himself as a sort of aside to his career, either — he was so good at publicity that his books were just as successful as his actual cooking career, and the publishing boom allowed him to withdraw from the kitchen a bit.

Marie-Antoine Carême's cookbooks changed how we share recipes

Take a look at medieval recipes and you'll find they're very inexact. They'll call for things like a little of this, a bit of that, a few slices of this, and a handful of that. That's vague, and it also means the final product is going to taste different each and every time it's made. If you like having a recipe that's a little more concrete, you can thank Marie-Antoine Carême.

According to Columbia University professor of sociology and cuisinology Priscilla Ferguson (via Eater), "His most lasting change is that he systemized cuisine." He started with the basics, teaching people how to make, for example bouillon, then sharing more recipes that further built on that one concept. His cookbooks had a number of things that made them popular: they contained impressive drawings, they were relatively inexpensive, they were translated into different languages, and large print runs spread them all across Europe.

It's tough to stress just how successful he was: The Oxford Companion to Sugar and Sweets says that his cookbooks allowed him to turn sugar into gold and to establish "the cult of the chef." He's also credited with coining a phrase that celebrity chefs like Rachael Ray have built their careers on, and that's the simple "you can try this yourself at home."

Marie-Antoine Carême helped spread fine French cuisine to Britain

Something else happened to Marie-Antoine Carême in 1815, says The Guardian — he headed to England, and was commissioned by the future King George IV to become the chef at his residence in Brighton (pictured). Sources vary, (with Brighton Museums saying it was 1816 that Carême went to Britain), but we do know that George IV was so proud of his chef and his kitchens that he gave guests a tour of them along with the more traditional rooms of his state apartments — and that made it one of the first ever "show kitchens."

While he was there (he left in 1817), he made a lasting impact on the country's cuisine. The king was particularly fond of his confectionary creations, some of which stood four feet tall. Some of his menus still survive, and contain dishes like "Marinaded haunch of boar," "Great Parisian meringue," "Ducklings Luxembourg," and dessert centerpieces that included an Italian-style pavilion and a Swiss hermitage. Clearly, his was an international influence and it made elaborately-designed banquets the stuff of royalty and opulence.

Marie-Antoine Carême taught us to care about food presentation

You've heard sayings referring to how the first bite is with the eye, but that wasn't always a popular opinion. According to NPR, it was Marie-Antoine Carême who first put a serious emphasis on what a table looked like, instead of just focusing on what a dish tasted like.

He encouraged others to think about it, too, writing in one of his cookbooks, "I want order and taste. A well displayed meal is enhanced one hundred per cent in my eyes."

Carême wasn't, the saying goes, just another pretty face. The contributions he made to cuisine — particularly French cuisine — are extensive, and according to the Auguste Escoffier School of Culinary Arts, Carême is considered the founder of French gastronomy. While Escoffier is known as the one who established many of the kitchen systems used today, he built his work on the shoulders of Carême and, particularly, on his idea of food as art. Anyone who has ever heard Gordon Ramsay go on about how important presentation is, well, now you know where the idea came from.

Marie-Antoine Carême founded the idea of the mother sauces

One of the main building blocks of French cuisine are the so-called "mother sauces," the sauces that every chef worth his salt should know how to make. They're the basis for a wide variety of recipes, and they have their roots in Marie-Antoine Carême's work.

According to the Auguste Escoffier School of Culinary Arts, it was Escoffier himself who finalized the group of mother sauces: hollandaise, bechamel, veloute, tomato, and espagnole. But it's not that straightforward.

They also say that Carême first developed four mother sauces, based on the same idea that it was these few sauces you needed to master before moving on to bigger things. His were sauce tomat, bechamel, veloute, and espagnole. Escoffier later added hollandaise and a whole slew of so-called "daughter sauces", and Carême, too, had a number of signature sauces. But by distilling those myriad of sauces and techniques down into just a handful, it created a base for countless dishes — a base that was easy to teach and master — and formed the backbone of an entire cuisine's techniques and ultimately, dishes.

Marie-Antoine Carême developed the traditional chef's uniform still in use today

Imagine what a chef working in a high-end restaurant is wearing, and chances are good you'll imagine the classic chef's uniform, the one that includes a tall white hat and a white coat. But where did that come from? According to The Culinary Institute of America, if you go back to the Middle Ages, you'll find cooks were identified by aprons. Different countries had different ideas about traditional colors and styles, but it was Marie-Antoine Carême who had a hand in standardizing the look.

First, says NPR, he favored white because of the image of cleanliness it gave, and Carême was all about appearances. He was also the one who introduced the idea of the tall, stiff hat, and he made his by putting a round piece of cardboard in a what was a normally flat hat. In spite of the fact that British chefs held out in adopting it, it caught on as the trendy thing to wear.

The jacket was quicker to catch on, and Carême first sketched the now-traditional double-breasted jacket in 1822. It was standard by 1878, and it was practical: since the flaps could be folded either way, it provided double the protection against heat and splatters, and it could appear clean for twice as long. Those long sleeves are a bit of practical protection, too, so it's no wonder chefs still follow in Carême's footsteps.

Marie-Antoine Carême tried to re-imagine St. Petersburg

Many celebrity chefs seem to come with a certain sense of superiority over their associates, and from what we know of Marie-Antoine Carême, he was definitely a trendsetter there, too — and there's a great story that speaks volumes to his audacity.

Historian Darra Goldstein says that Carême was first introduced to Tsar Alexander I in the years between 1814 and 1818, when the Russian ruler was traveling repeatedly to France for various negotiations. There, he met the chef and tried repeatedly to get him to the Russian court to cook for him and his family. Carême refused, until finally heading to St. Petersburg in 1819. It was a short trip, though, and he soon returned to France without ever cooking for the Russian rulers. Why?

In addition to being outraged that the Tasr hadn't personally met him on the docks, he believed their royal kitchens were beneath him, and their capital city was much too short.

Transportation being what it was, Carême had to wait weeks for the next boat home. He spent the time wandering the city, and found it was nowhere near grand enough for the city that it was supposed to be. Most of the buildings were on the short side, so Carême did a series of sketches for monuments that he thought you raise the profile and grandeur of the Russian city. They were never built — St. Petersburg is on a swamp, and swamps don't mix well with tall buildings.

You wouldn't have wanted to try all of Marie-Antoine Carême's food

Certainly, if you had the chance to eat a meal prepared by Gordon Ramsay or Emeril Lagasse, you'd jump at the chance, right? You might think you'd do the same for Marie-Antoine Carême, too, and you almost can: many of his cookbooks are still in print. But for as brilliant as his desserts look and as familiar as some of his creations sound, some of his recipes are still... well, let's put it this way — you would want to know what's in it before you took a bite.

NPR shared one of his recipes for Les Petits Vol-Au-Vents a la Nesle, one of the recipes he served when he was in England. There are some ingredients that sound pretty normal, like truffles, mushrooms, and lobster tails. That's about where it ends, though, and here's the other ingredients: roosters' combs and testicles, lamb sweetbreads (which is the pancreatic glands and the thymus) and brains, chicken jelly, and calves' udders. That's just one recipe, and it essentially calls for taking all of those things, boiling them, pushing them through a sieve, and forming little balls of meat. Yay or nay?

It was his passion that killed Marie-Antoine Carême

So, what happened to Marie-Antoine Carême? Sadly, he died young and tragically. According to Webster's Prime, Carême spent his last days writing and suffering from a disease that, at the time, doctors believed to be intestinal tuberculosis.

In reality, it was something else. Carême had spent years working in kitchens with coal fires and little to no ventilation, and the smoky environment took its toll. He was pretty constantly suffering from mild carbon monoxide poisoning, and on January 12, 1833, he suffered a stroke related to his lifetime of work in the kitchen. He was just 49 years old when he passed away, but he left quite the legacy.

He also left these words to anyone thinking of following in his footsteps: "Advice to young chefs: young people who love your art; have courage, perseverance... always hope... don't count on anyone, be sure of yourself, of your talent and your probity and all will be well."