False Facts About Tuna You Thought Were True

Tuna is an intriguing fish. Depending on its type, it can weigh up to 2,000 pounds and measure as much as 13 feet in length. Furthermore, it can have a lifespan of over 20 years and reach speeds of 50 miles per hour. Beyond its impressive physical capabilities, tuna also holds a significant place in the culinary world. Popular for its rich flavor and versatility, the ubiquitous fish is a mainstay of various cuisines around the world.

Tuna can be found in the upscale environs of a sushi bar just as easily as it can be spotted in a family kitchen, making it a staple in a variety of culinary settings. From elegantly plated sushi and sashimi to the comfort of a simple tuna melt, the fish easily transcends gastronomic boundaries. Canned tuna adds another dimension to tuna's versatility, making it ideal for spur-of-the-moment meals. This pantry staple can be easily transformed into numerous dishes, ranging from a tuna salad to more creative inventions like tuna patties and healthy tuna wraps. Despite its popularity among chefs and home cooks alike, tuna is often surrounded by misconceptions. Ready to unravel the truth? Keep reading!

False: There's only one type of tuna

The belief that all tuna is the same likely originates from the oversimplified labeling of tuna products. Instead of highlighting the specific species, many restaurant menus rely on the catch-all term "tuna." Similarly, some supermarket canned tuna products come with non-specific labels such as "chunk light," which not everyone understands (this can mean a mix of skipjack, yellowfin, and bigeye tuna). While this approach simplifies marketing and sourcing, lumping all tuna species together disregards significant differences in taste, texture, and nutritional value among the different types of tuna.

Among the 15 different types of tuna, the most popular are albacore, also called white tuna, and skipjack, also known as light tuna. Albacore is characterized by a solid, chunky texture and large flakes, offering a mild to medium flavor that appeals to those who favor a less intense fish taste. Skipjack, on the other hand, is darker and has a stronger flavor, making it the most common type used in canned tuna. Other popular tuna species include yellowfin tuna, which is pale pink in color and mild in flavor, making it a popular choice for sushi and steaks. Frequently used in sashimi, bluefin is a more prestigious member of the tuna family, praised for its marbled flash and buttery texture.

False: All tuna species are overfished

Tuna species don't just vary in taste and texture, they also differ significantly in their habitats, lifespans, and the ecological roles they play in marine environments. These differences can influence how susceptible each species is to overfishing. However, while we often hear concerns about the depleted tuna numbers, in reality, only a relatively small minority of tuna species face a significant threat.

According to the International Seafood Sustainability Foundation, which conducts regular assessments of tuna stocks, most of the world's tuna populations are managed sustainably. This means that they are not being caught at a faster rate than they can reproduce. As per the foundation's 2023 report, only 17% of tuna are currently overfished, with 61% of tuna stocks worldwide at a "healthy level of abundance" and 22% at "an intermediate level." And the situation seems to be improving. In 2021, yellowfin, albacore, and the Atlantic bluefin tuna were removed from the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Meanwhile, the status of the Southern bluefin tuna was downgraded from critically endangered to endangered.

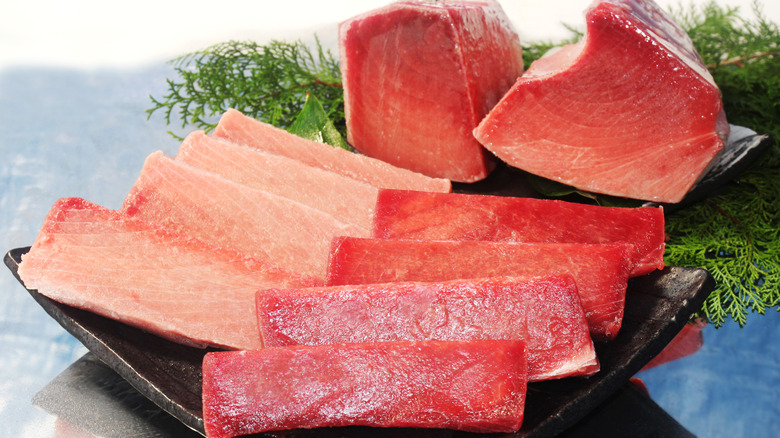

False: All tuna meat is the same color

Individuals unfamiliar with fresh tuna might be unaware of the differences in color among the various species. For instance, albacore has the palest meat of all the tuna types. Meanwhile, yellowfin is pale pink and bigeye is dark red. However, the color variations don't stop at these distinctions. Once tuna is caught, its meat gradually changes color over time.

Just like beef, tuna contains myoglobin, a protein that gives it its reddish color. Over time, as the tuna is exposed to oxygen after being caught, the myoglobin undergoes a chemical reaction, leading to a gradual change in the fish's color from red to brown. This color shift can take place within mere hours if the fish isn't frozen. Since many customers find brown-hued tuna unappealing, the seafood industry developed methods to maintain the color of tuna for prolonged periods of time.

One such method involves treating tuna with carbon monoxide. However, once exposed to the substance, tuna will stay bright red even after it's no longer safe to eat. This preservation technique has been outlawed in the E.U. and Canada but remains legal in the U.S. The bans have been enacted due to concerns that carbon monoxide could be used to conceal spoiled fish.

False: Tuna always contains high levels of mercury

Many people are under the impression that all tuna is packed with mercury due to widespread media reports and public health warnings about the dangers of mercury in fish. These advisories frequently highlight the potential health risks associated with the ingestion of mercury, such as neurological damage that can affect such vital functions as motor coordination and speech.

However, what these warnings fail to point out is that not all tuna — and not all seafood — contains the same levels of mercury. In addition, giving up tuna altogether might not be the healthiest move since the fish is packed with omega-3 fatty acids, vitamins A, B-complex, and D, as well as selenium, iron, and phosphorus.

Different varieties of tuna have varying mercury levels, and many are considered safe to eat in limited quantities. Skipjack tuna, which appears on the FDA's "Best Choices" list, contains the least mercury of all tuna species and less than a lot of other seafood options. Meanwhile, both albacore and yellowfin tuna have been classified by the same agency as "Good Choices" when it comes to seafood. However, it's best to steer clear of bigeye tuna, which features on the FDA's "Choices to Avoid" list due to its high mercury content.

False: All tuna is expensive

While some types of tuna command top prices due to their scarcity and gourmet status, not all tuna is expensive. Varieties such as skipjack and albacore are abundant and affordable, with both fish types priced at just over $20 a pound. This is why species are usually used in canned products. Notably, skipjack tuna represents more than 70% of the U.S. market for canned tuna because the fish matures relatively quickly, reproducing at just one year of age. Additionally, at around $35 per pound, yellowfin is a great mid-priced tuna choice, which is frequently served as sushi and steak.

The pricier species of tuna are valued for their distinct flavor, texture, and comparative rarity. For instance, bigeye tuna can fetch around $42 per pound. The priciest tuna type is bluefin. In fact, Atlantic bluefin tuna can set buyers back thousands of dollars a pound. Weighing up to 1,000 pounds, bluefin tuna is popular in the Japanese sushi and sashimi market. Earlier this year, a 525-pound bluefin tuna sold for $800,000 at an auction in Tokyo. The humongous fish was purchased by Onodera, a Michelin-star restaurant in Japan's capital city.

False: All tuna is harvested in an environmentally irresponsible way

The idea that tuna fishing is always detrimental to the environment is rooted in both outdated fishing practices and current ecological issues. Irresponsible fishing techniques, including the use of drift nets, fish aggregating devices with purse seine nets, and long line methods, have contributed to an excessive by-catch of marine life like dolphins, sharks, and sea turtles. Additionally, the overfishing of some tuna species has led to a decline in their numbers, leading to worries about the future sustainability of these stocks and the overall health of the marine environment.

Luckily, tuna harvesting practices that aren't detrimental to the environment do exist, highlighting a more sustainable approach to fishing. Today, many fish come from fisheries with a robust stock and effective management that have a minimal impact on the surrounding marine ecosystem. To avoid contributing to overfishing and environmental degradation, look for tuna sourced from U.S. fisheries and steer clear of imported tuna, particularly fish caught using unsustainable fishing practices. In addition, stay away from bluefin tuna and any tuna that originates from the Indian Ocean. When reading labels, look for the following fishing methods: pole-&-line-caught, pole-caught, troll-caught, school-caught, and FAD-free.

False: Pregnant women shouldn't eat any tuna

Concerns about mercury exposure have led some pregnant and breastfeeding women to stop eating the fish completely. In reality, the FDA advocates against this practice since seafood is full of nutrients essential for fetal growth and development, including omega-3 fatty acids, protein, iodine, and zinc. Instead of avoiding seafood entirely, the FDA advises pregnant and breastfeeding women to consume fish low in mercury and to limit their consumption of higher mercury fish.

According to the FDA, pregnant or breastfeeding women should consume two to three 4-ounce servings of seafood from its "Best Choices" list a week. Aside from other fish options such as butterfish, tilapia, and sole, this list includes skipjack tuna. Alternatively, they can opt for one 4-ounce serving of seafood from the FDA's "Good Choices" list, which includes both albacore and yellowfin tuna. Young children can also benefit from eating tuna, as long as it's skipjack, which is low in mercury.

False: Frozen tuna is inferior to fresh tuna

The preference for fresh over frozen tuna is often rooted in the belief that placing fish in the freezer can affect its taste, texture, and nutritional value. In reality, unless you're lucky enough to be consuming tuna shortly after it's been caught, it's actually preferable to freeze it. Firstly, the so-called fresh fish you're buying at the supermarket, may not be all that fresh, owing to the time delays associated with transit, distribution, and processing. Additionally, the longer the interval between the time the tuna is caught and consumed, the more likely it is that the fish becomes infected with bacteria.

In many cases, freezing fish is preferable to keeping it fresh for both practical and safety reasons. This type of preservation is crucial for maintaining quality, especially when the seafood needs to be transported over long distances. Freezing also extends the shelf life of tuna, enabling consumers and businesses to store fish for longer periods without sacrificing quality or safety. Additionally, subjecting tuna to low temperatures kills parasites, reducing the risk of foodborne illnesses. For this reason, a lot of the fish used in sushi and sashimi have previously been frozen. Last but not least, freezing tuna doesn't deplete it of its nutritional value as long as the fish has been frozen shortly after being caught.

False: Canned tuna isn't healthy

While convenient and affordable, canned produce is often perceived as less nutritious than its fresh counterpart. Canning requires the use of high temperatures that can sometimes reduce the nutritional value of the food, especially vitamins B and C, which are water-soluble. Additionally, canned foods can be relatively high in sodium, sugar, and preservatives.

While these are valid concerns, canned tuna has plenty of health benefits. For starters, it's rich in protein and boasts an array of beneficial minerals and vitamins, such as vitamins B-12 and D, as well as iron and potassium. Perhaps counterintuitively, canned tuna also contains more omega-3 essential fatty acids than fresh tuna. However, not all canned tuna is created equal. Tuna packaged in oil tends to have higher levels of sodium and calories, and slightly more fat, including saturated fat, than tuna packaged in water. Meanwhile, the protein found in canned tuna preserved in water or oil is on par with the protein content of fresh tuna.

False: Tuna has to be cooked thoroughly

Unlike some other produce such as chicken, tuna doesn't have to be cooked completely to be safe for consumption. Indeed, overcooking tuna can result in a dish that's both dry and flavorless. Instead, many prefer their tuna raw or lightly seared, relishing its richness and succulence. In Japanese cuisine, dishes like sashimi and sushi showcase the tender texture and subtle flavors of raw tuna. Similarly, just like beef steaks, tuna steaks are often left with a rare or medium rare center that's both pink and moist. Tuna tataki is one such dish. Seared over high heat, the culinary creation features a raw, cool center and a slightly caramelized exterior creating a wonderful contrast between textures and flavors.

While eating raw fish carries a risk of foodborne illnesses, tuna is deemed comparatively safe due to its low risk of parasites. The practice of freezing fish at temperatures that kill parasites before it's consumed raw further minimizes any health risks. Nevertheless, it's still crucial to source tuna from reputable suppliers to minimize the chances of ingesting subpar fish.