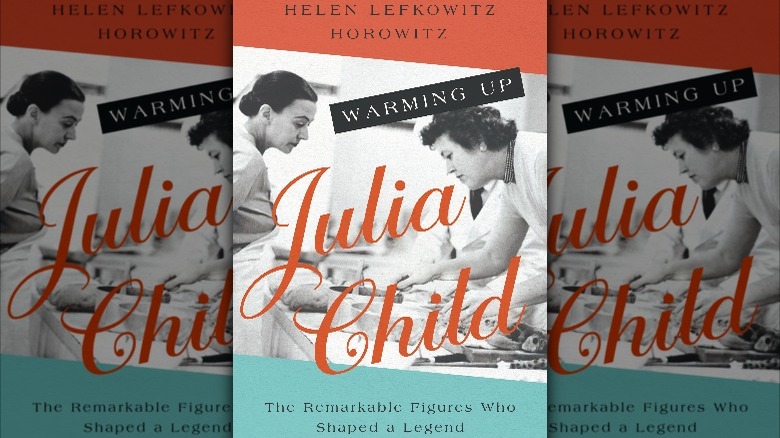

Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz's New Book Sets The Record Straight On Julia Child - Exclusive Interview

Pulitzer Prize-nominated Historian Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz has an insight into the passions and ambitions of Julia Child that few have been gifted with. The story she tells in her newly-released book, "Warming Up Julia Child: The Remarkable Figures Who Shaped a Legend," is born largely out of Julia and Paul Childs' personal records. They're letters and correspondences that bring to life not only Julia's tenacity but also the extraordinary support system she wove around her, without whom Child's odyssey would almost certainly have failed.

The journey to publishing "Mastering the Art of French Cooking" was, Horowtiz's book reveals, a challenge of Marvel superhero-worthy proportions. Had it not been for her network, including Julia's husband Paul Child, her close friend and advocate Avis DeVoto, and her fellow collaborator Simone (Simca) Beck, we may never have become entranced with the Coq a Vin. We might never have dared to take on a Boeuf Bourguignon. We may never have allowed ourselves to love, as Child unconditionally did, butter.

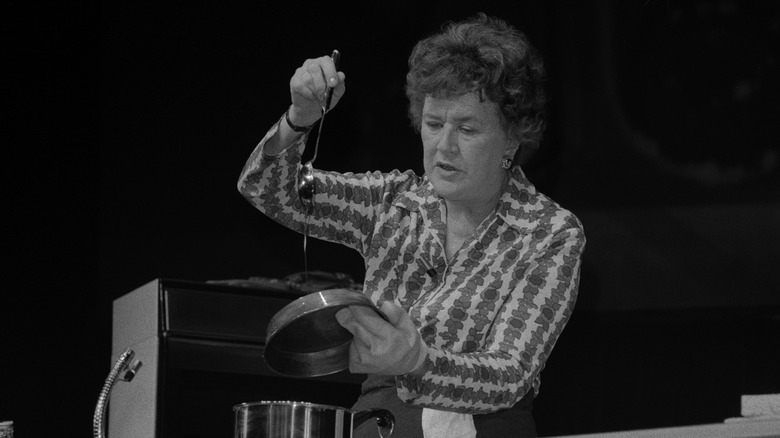

Cooking was no past-time for Julia Child, nor was it a job. It was, in Horowtiz's words, "her way of life." Once she discovered her omelet pan, she never parted with it. In this exclusive interview with Mashed, Horowitz explores Child's superhuman zeal, lifts the lid on her support network, and talks coming face-to-face with Child herself.

Meeting Julia Child

What was different from the Julia Child you got to know through her letters from Julia Child, the myth that we all have in our head?

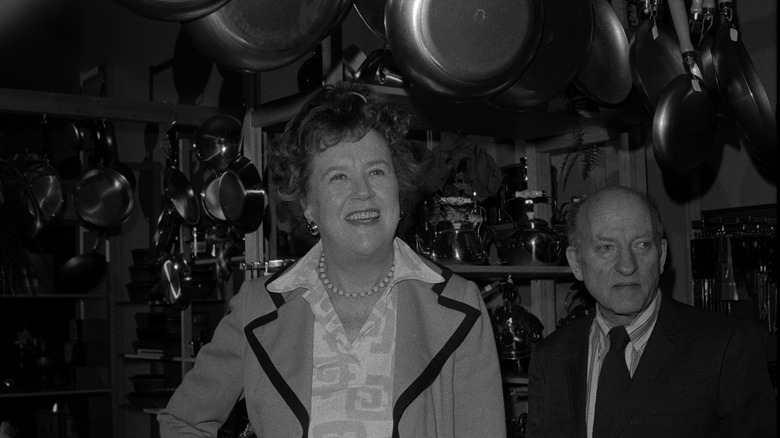

I was lucky enough, when I was at Smith College, to meet Julia Child twice. The first time was when Mary Dunn was inaugurated as president. Smith had Julia Child plan all the meals and supervise the kitchen over the inaugural weekend. Julia Child didn't cook for the event, but she volunteered her time to make it special by devising the menus and recipes. My mother-in-law went to Smith, and I invited her and my father-in-law to come and enjoy the weekend with me. I was then teaching at USC in Los Angeles, but I was invited to Smith because the college planned an educational event on my book, "Alma Mater." I was supposed to respond to about five people's criticism or comments about it, which was fun.

I went to Smith and had my in-laws come early. We were eating in the Smith faculty dining room, and Julia Child walked out and greeted everyone. She came to every table, and shook every person's hand with words such as, "I hope you're enjoying your stay." She was very gracious. It was a wonderful moment that I remember very keenly. Then, at the reception she planned for that followed the inauguration, she went around and talked with everyone. Some years later, when I was on the faculty at Smith, she came to help the college as it opened up a capital campaign. She was one of the people on the stage, saying, "Go for it, folks. This is important." She was an extremely friendly person.

Julia Child's support network revealed

As you got the opportunity to sift through all of these archival letters and notes, what struck you the most?

What struck me the most was what I turned out writing about: the way [that Julia Child] bonded with people, the way they became her coworkers in a project. First [was] Simone Beck — Simca, [and] Paul was a little different. He was bonded to her for life in a wonderful way, and though he was a moody person and probably a little cranky, they adored each other. They were very different personalities and that worked out really well for them. As I went along, I added people and found correspondence that was rich between them, and realized how much her success was involved with other people working with her. That's what I wrote about.

There were so many kinds of independent women were part of her team during the '50s. You have Avis DeVoto, who lost her husband. You have Simca Beck, who divorced. You have Judith Jones, and then you have Ruth Lockwood. Even Paul Child's mother was a single mother, who brought him up. Could speak to how this might be significant to the support network that Julia built?

That's a really interesting question that I had not anticipated. At the point in which Julia got to know Simca, Simca was in a very happy second marriage, but Julia didn't know her in her earlier life when a first husband was presented to her by her father. They really didn't know each other when they married. It was a very sad period in Simca's life, but Simca came out of that very strong. That probably had some real impact on Julia because she was aware of how strong Simca really was. Simca was argumentative. Simca was forceful. Simca would fight ... if she thought a dish needed this kind of vinegar, it was going to have that kind of vinegar. That probably strengthened Julia's hand.

Avis had to become an independent person. She realized how dependent she had been on Bernard [her husband] through the tragedy of his sudden death. She had to earn money and go to work. She actually got very good at employment, in time. She learned how to type –- to do professional typing -– all sorts of things like that. That showed Julia someone with real grit — that she could pull out of that experience of the death of a beloved husband and learn how to support herself and her family. I actually became a friend of her son, Mark. He's a wonderful human being. I think about that every time I interact with him. I think about what kind of a mother he must have had, because he was young at the time that his father died.

Why Julia's recipes were 'top-secret'

There are all of these references in Julia's work about the "top-secret-ness" of the recipes. What was at stake for her?

She was aware. She was from a business family. Her father was in real estate investment and real estate planning and such. She was aware that things that she was creating, methods of doing things, could be stolen. She wanted people to test her recipes. She wanted her friends, her California friends, to do that. She certainly wanted Avis to do that, and Avis was one of her best testers. We have the record of that. We don't have the record of the other testers, but she knew that a recipe, once out there, she didn't have a copyright on until she published it. She was very savvy.

One of my readers is a business historian, and she thought I needed to really emphasize that side of Julia. I went back and rewrote after that, because it did seem to me that Julia had developed a clear sense of the competition. She was nervous; remember, also, about what it was going to be like to come back to the U.S. when the gang in New York was tight with each other and wasn't going to welcome her. That's why James Beard was so important, because he welcomed her — not the way it was shown in the series, "Julia," by any means. He welcomed her as someone he admired and wanted to cook with.

What cooking meant to Julia Child

The idea that "Mastering the Art of French Cooking" was in the works for about a decade before it was finally published speaks to an incredible tenacity. Julia's talking about it [from very early on] as if it's going to really change the paradigm of cookbooks. It's an extraordinary amount of confidence in something that's hard to wrap one's head around!

It's hard for me to wrap my head around, too, because her self-confidence was amazing. She believed in herself and what she was doing. She knew that if she tested things right, and applied her sense of science to it, that it would go well. She did things over, and she tested things over and over. There was one point in the book you might notice when Paul wanted to get out of soups. He was sick of soups because they did eat what she tested. She didn't throw anything away, as far as I could tell.

She had an enormous amount of endurance and a strong belief in herself, and she wasn't going to let anything go out into the world that had any possibility of mistake. They tested, and tested, and tested. Then she sent it to people, and they tested it. These were her California friends. We don't know who they even were, and then she had Avis for a tester.

Is there one particular recipe that you found that she had a lot of joy in perfecting?

Nothing really struck me that way. I saw her as someone who worked every day. Even when she was enjoying things like traveling, she was testing other people's food, wanting to find out how was that done, seeing if she could get into a kitchen — those kinds of things. She was like a musician, in a way. She was totally dedicated to what she was trying to accomplish. That impressed me the most, [along with] her sense that she had to protect her material 'til she had a copyright on it.

You write in the book that for Simca cooking became more than putting food on the table. It became an important creative outlet. Is that what cooking became for Julia as she dove into this process?

I would say truly so. Julia was reflecting on Simca, but she also knew that had happened to her. She was cooking at least five hours a day, testing and working. It never stopped. When they began to spend time in Provence with Simca, after they moved to America, guess what they were doing? They were working in that kitchen again. When Simca came to visit, what were they doing? Working in the kitchen. It was her way of life. It was her creative outlet. You don't think about an artist taking a vacation from sketching. Artists I know take their sketchbooks with them, and she was like that. It was an art for her as well as a profession.

Inside Paul and Julia Child's relationship

Can speak about Julia and Paul Child's relationship? It seems like such a dynamic relationship hidden in these pages.

They loved each other tremendously and knew each other really well because before their courtship, they had been in two places in foreign lands together in the foreign service. They both loved food. Paul ... we see him at a later stage. As a younger person, he had a sparkle to him. Julia did [too], and they knew by the time they returned to the U.S. that they were truly a couple. He was always on her side. I'm not really aware of a quarrel between them that ever surfaced in their papers.

I not only had papers of them when they were separated, but I had his papers to his twin brother, where he wrote a lot about Julia and what she was doing. Those were among my most helpful documents. He respected her tremendously. She respected who he was, though he was so very different from her. He was introverted when she was so very extroverted, but he relished her company because of her warmth. She relished his honesty. I don't think he never pretended with her. She knew she could get the truth. If she cooked something badly, he would eat it, but he would not praise it.

They were devoted to each other.

The test that Julia Child failed

You write in your book about the time that Julia fails her Cordon Bleu examination and the rage she feels. Can you speak to that a little bit? And also how pivotal a point is that in her life?

She was very angry because she thought that she was going to be tested on the hard parts, not the easy parts that she had passed over. As a result, she hadn't practiced those. She practiced the hard parts. Again, would you practice the scales when you were going to be tested or would you practice your recital music? It was that way with her. She did the hard stuff. She was really outraged because she knew how to do it, and she knew she was good. She knew because of the results. She was a woman who loved to eat, and that made a big difference. She learned some techniques at the school, but she also felt it was too elemental and she wanted to take it to different levels.

Through your book, it becomes so clear that Julia was never going to be somebody that was standing on the sideline without any personal passion project of her own, even if she hadn't stumbled upon cooking and her love for food the way she did. Could you guess what she may have dedicated herself to if she'd never gotten into cooking?

Boy, that's a tough one. I really don't know. When she was in Paris, or when she was in France, she not only had the revelatory meal, it was the best food she'd ever had, but she tried other things. She tried hat making. She knew she had to do something. What was she going to do when Paul was at the embassy every day? She wasn't from a social class that was going to scrub the kitchen floor every morning. What was she going to do? She tried out a number of things, and then she decided she wanted to learn how to do things better as a cook because the markets were so wonderful. She went to the markets, and got the food, and she had the lessons that were very elementary.

She was also a person who could bond with people. She bonded with Chef Bugnard. He gave her lots of private lessons, and she had the money to afford that. Her mother died when she was a young woman and left her a considerable amount of money. She never used the principle — she only used the dividends. She was wise about that. When she had to live lean, she lived lean. It did mean that she didn't have to work, even when Paul wanted to give up work.

Helen Horowitz fact checks

You've mentioned a couple of discrepancies between the television series, "Julia" and what you discovered or know from your research. Can you speak to that a bit? What does the television series misconstrue, and what does it do right?

What it does right is the actors. They really embodied the characters so well. That was true of both of the persons, Sarah Lancashire, who played Julia, and David Hyde Pierce, who played Paul, and the person who played Avis. They really made those characters come to life in a wonderful way. They got some facts really, really wrong, and the one I concentrated on was WGBH and The French Chef. How did she get there?

She didn't get there by offering to pay them money, and she didn't get there under the opposition of the men. [How] she got there came after she appeared on the "People Are Reading" program by the BU professor. The television, WGBH, got 27 letters applauding the program when she came with this skillet, and her eggs, and made an omelet on a hotplate. It's hard to believe that 27 letters is a persuasive number, but this was early in public television.

A cousin of a person who was a major producer at WGBH, Miffy Goodheart, came and had lunch and tried to convince Julia to think about a television show. They drafted a woman by the name of Beatrice Braude, who they knew in France because she worked at the embassy with Paul and was a friend. She was now actually on the staff of WGBH, not just a relative of someone on the staff. She helped Julia draft a professional proposal of what it would look like. What would the contents of the program be? WGBH decided to have a trial run.

I think they taped three ... In this era, at WGBH, it wasn't direct person-to-home TV screen. Shows were taped. They taped three programs and tried them out, and they were very, very successful. Julia worked hard to rehearse them. That's when my character, Ruth Lockwood comes in, who is not represented by the person playing the part of the helper. Ruth Lockwood was a middle-aged woman who had graduate training, an MA in television production at Boston University, and in mid-life, she started to work at WGBH first as a volunteer.

She was a volunteer for many years, and she devised the idiot cards that you see. The show has Paul running up with a poster. Instead, what the staff realized they needed was about five people in the back holding up posters. ... This was for a segment. They would give Julia the times left for each segment, and if she made a mistake, they would hold up a correction. They had this good team of people working for them. These are some of the differences.

If you're enjoying watching "Julia" the series, dig a little deeper! Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz's book "Warming Up Julia Child" is available for purchase here.