The Untold Truth Of Avis DeVoto

Julia Child, the exuberant cooking personality, and her revolutionary book "Mastering the Art of French cooking" are rightly celebrated as some of the foremost influencers of modern America. Indeed, Child and her book introduced the wonders of French cuisine to the wider American public, igniting a passion which would last for decades and kickstarting a "foodie" culture which still has the nation firmly within its grasp.

However, the ease with which Child sprung onto our screens, and her book settled into our kitchens, belies the tortuous process of trialing, writing, and editing that accompanies the birth of every great cookbook. By her side coaxing and cajoling, editing and rewriting, playing midwife through it all, was Avis DeVoto. This was not the first, nor would it be the last, revolutionary book DeVoto helped deliver into the world. Yet, with so much attention being paid to the authors her contribution to America's culinary heritage has been largely overlooked. In a bid to right this wrong here is the untold truth of Avis DeVoto.

DeVoto and Child's friendship was triggered by a knife

In 1951, Bernard DeVoto — Avis' husband — launched an impassioned tirade against the sorry state of American stainless steel knives. His attack on these edgeless, blunt instruments was published in Harper's magazine and found its way to Paris where it was read by an American named Julia Child. Instantly recognizing a kindred spirit in the war against subpar culinary apparatus, Child penned a heartfelt letter to DeVoto and included, by way of a gift, a small 70-cent carbon steel French paring knife.

Bernard DeVoto was not one to answer the majority of his mail. This rather tedious job was often left to his wife. So it came to pass that Avis DeVoto was the one to receive Child's heartfelt letter before replying with her own kind response. Part of her reply which reads (via New York Post) "My husband, I regret to say, has snitched it [the knife] for his own use — cutting the lemon peel the proper thickness for the six o'clock Martini" hints at the shared culinary passion, and love for writing which would define DeVoto and Child's long friendship.

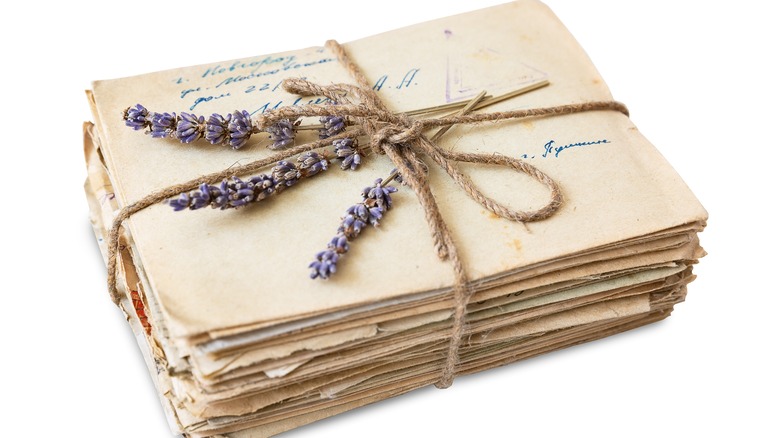

The women sent each other 120 letters in their first two years of friendship

Letter writing seems a dated and tedious process to most in today's high octane world. Yet, it is that commitment, both in time and effort, which lends the medium its power to bring people together. This is exemplified by DeVoto and Child's early correspondence. Separated, as they were by the Atlantic Ocean, and without access to alternative means of communication, letters provided the only means of communication between the two during the first 24 months of their friendship. A strong bond was created with 120 letters being sent between the two (per New England Historical Society).

These letters, and others from further years have been collected in the book "As Always, Julia." In these pages, you witness the slowly melting formality, which is replaced by affection, keen intelligence, and hilarious commentary on the two women's lives. Yet perhaps most striking of all is the support given by DeVoto for Child's encyclopedic book project, which would ultimately become "Mastering the Art of French cooking". On February 27, 1954 DeVoto wrote "Just to say how absolutely wonderful I think the egg chapter is. It came this morning. I started it this afternoon. Interrupted only to get dinner and clean up after. Just finished. I am absolutely overwhelmed by the amount of work you have put into this. Swept off my feet. Knew before how good the book would be but never felt it quite this way before. Masterly. Calm, collected, completely basic, and as exciting as a novel to read."

Avis Devoto and Julia Child met for the first time at a cocktail party

In an event so stylish and fitting you would think it lifted from a Hollywood script, the Childs and DeVotos first met in 1954 at a cocktail party hosted by the DeVotos in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Now, if Bernard DeVoto's highly opinionated cocktail book, "The Hour," is anything to go by, cocktail parties were a very serious business in the DeVoto household. Guests would be drinking martinis and whiskey, or face the sneering wrath of Mr. DeVoto himself. No fruit juice would be allowed within a kilometer of the door and the word "rum" could not even be whispered.

It is humorous then to imagine the exuberant scenes which must have unfolded when the Childs rolled up to the house in, as told by Avis DeVoto (per New England Historical Society) "A large station wagon ... loaded to the roof with pots and pans and equipment of all kinds." This first meeting, cacophonous as it must have been, cemented the friendship between Avis DeVoto and Julia Child, ensuring it would firmly last until DeVoto's death in 1989. How their meeting is described by Juia Child in a letter to DeVoto highlights the love the two women shared "It doesn't seem at all possible that less than two weeks ago you were all of you but words on paper ... It did not then seem that love on paper would not blossom into love in the flesh, and it certainly did with an all-embracing bang."

The DeVotos and the Childs were near enough neighbors

After deciding that diplomat Paul Child's final posting would be to Oslo, Norway in 1958, the Child's set about searching for their permanent residence. Buoyed by their love for the area, and the number of friends they had in the vicinity, Julia and Paul Child set their heart on Cambridge, Massachusetts.

As reported by Child in an article she wrote for Architectural Digest, Avis DeVoto, who lived in Cambridge with her husband Bernard for the majority of her life, agreed to keep her eyes open for potential properties. Just a few weeks before the Child's were due to fly to Oslo, DeVoto called the Childs' home in Washington and implored them to come view a property as soon as possible.

The property at 103 Iriving Street, was to become Julia Child's house for 40 years and the kitchen, designed by her husband Paul Child, and executed by architect Robert Woods Kennedy was to become the studio for three of Child's TV series, before she donated it to the Smithsonian where it can still be seen on display.

DeVoto played a key role in the publication of Mastering the Art of French Cooking

It was the book that changed American cooking forever. Julia Child, Simone Beck, and Louisette Bertholle all met whilst training at Le Cordon Bleu, and set up a cookery school called "L'école des trois gourmandes" or "The School of the Three Hearty Eaters" (viaThe New York Times). Eager to write a French cookery book for an American audience, the three set about this gargantuan task with the aim of simplifying the often over-complicated recipes with clear measurements and instructions for all the required steps.

The manuscript came in at a massive 800 pages, giving some indication of the challenge facing DeVoto who had taken it upon herself to act as initial editor. By all accounts she did a wonderful job, guiding Child away from a small publisher to Houghton-Mifflin (via Los Angeles Times). Houghton-Mifflin turned the book down on the basis that the recipes were too complicated and the book too long. It was one of two rejections which led Child to write to DeVoto "I am deeply depressed, gnawed by doubts and feel that all our work may just lay a big rotten egg." Avis DeVoto, never one to give up, hand-delivered a physical manuscript to connections she had at another publisher, Alfred A. Knopf who decided to take it.

The published book performed extremely well with over 100,000 copies being sold in less than five years. It finally became a bestseller in 2009, 48 years after the original publishing.

DeVoto and Child did not always agree on culinary topics

Avis DeVoto was not only an extremely talented editor and supportive friend but a fantastic cook in her own right. As such, she had strong opinions about food, and often lamented the lack of fresh quality produce in the U.S.

Unsurprisingly, this love for food and flavor formed the basis of DeVoto's and Child's relationship. Playful pokes at each other's likes riddle their letters. In one particular instance, Child detests the chives DeVoto sent to her stating "Tastes like hay with onion flavor" (via The New York Times).

For her part, DeVoto reminds Child of the limitations surrounding the sourcing of ingredients, and American kitchen practices; vital information for Child as she was writing "Mastering the Art of French cooking" for an audience that DeVoto directly represented. Examples include the lack of fresh fennel, which at this time was mainly found in dried form for medicinal use, and unnecessary instructions to clean eggs with wire wool as "we [Americans] never have eggs that dirty. Second place there's steel wool only nobody uses it in kitchens any more, only for stripping paint and so on. Death on the hands."

DeVoto successfully edited Elizabeth David's cookbook Italian Food

It was not just Child, Beck, and Bertholle who benefited from Avis DeVoto's masterful editing skills. Indeed, before "Mastering the Art of French Cooking" was published in 1961, DeVoto had already faced an even more substantial challenge; to bring the mercurial Elizabeth David's "Italian Food" to the U.S. market.

The book, which focused on the hitherto unexplored regional cuisine of Italy, and as reported by The New York Times, was a sensual phenomenon and had catapulted David to the status of culinary goddess in the U.K. However, cracking the U.S. would be quite another matter. American recipe books tended to be much more direct than "Italian Food," and Italian cuisine itself was not deemed desirable by the American public, this top spot being reserved solely for the cuisine of France. Add to this David's fierce reputation for defending her culinary opinion and you can see that DeVoto's work was cut out.

Despite having the tedious job of altering the measurements from British to American, and clarifying the recipes in order to make them more user-friendly, DeVoto still loved David's writing. She even decided to keep recipes which she knew could not be replicated in America. "Recipes impossible to duplicate in this country should be left untouched ... they are wonderful to read about ... Let the American housewife use her ingenuity, or go without." Unfortunately, despite its warm reception in the U.K., "Italian Food" never sold well in the U.S.

DeVoto was keen to preserve all of the Child's letters for historical records

It was not just food writing which caused Avis DeVoto's heart to flutter, but also an intimate correspondence between friends, family, and partners. With an unnerving understanding of their importance to the world, she implored both Julia and Paul Child to date and preserve any letters they received and sent to aid the work of future historians.

She was enamored with Julia Child in particular suggesting that her writing would reveal to future generations a comprehensive social history of the mid-20th century (via University of Rhode Island). Having been granted the honor of accessing the Child's early letters only made DeVoto more certain that everything must be stored for future generations. In November 1969 Devoto reiterated her point stating "I suppose somebody, sometime, will write a biography of Julia ... But I feel that the papers are even more valuable to future generations as a record of how one very special woman lived at this point in history."

As she so often did, DeVoto took it upon herself to make sure this happened, hand-delivering a large amount of written material to the Schlesinger Library on November 24th 1969, which included not only documents relating to Child, but Elizabeth David as well. Overjoyed with her achievement DeVoto stated "I like to think of somebody, 50 years from now, happening on to the letters of J. Child and E. David, in a library two blocks from Harvard Square."

Bernard DeVoto was a Pulitzer prize winner

It is funny how once previously impactful people drift into ambiguity with the passing of time. In his day Bernard Devoto was one of the most prolific historians and writers in America. Awarded the 1948 Pulitzer Prize for history for his book "Across the Wide Missouri," a study of the fur trade in the early 19th century Rocky Mountains. Between 1935 and 1955, Bernard DeVoto also ran an influential column for Harper's titled "The Easy Chair," and went on to be awarded a national book award for another book titled "The Course of Empire."

He met Avis DeVoto whilst teaching at Northwestern University where she was enrolled in his freshman English class and the two eventually moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts so Bernard DeVoto could focus on his writing. Both were outspoken critics of McCarthy with Avis DeVoto even complaining in a letter to Julia Child that she was beginning to feel like the U.S. was becoming a police state (via Los Angeles Times).

Criticism of the government led some to accuse Bernard DeVoto of being a communist. The rumors only gained traction when then-junior senator McCarthy accused Devoto of urging people to not give the FBI information regarding communist activities in the U.S. government (via the Harvard Crimson).

Avis and Bernard DeVoto were staunch protectors of the American West

Bernard DeVoto was not only a formidable writer but a very involved conservationist with political compatriot and Oregon senator Richard Neuberger labeling him "the most illustrious conservationist who has lived in modern times." Using his large platform, most notable through his monthly column in Harper's, Bernard DeVoto fought against the extraction of resources and commercialization of public lands leading DeVoto's old student and fellow historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. to call him "the first conservationist in nearly half a century, except Franklin D. Roosevelt, to command a national audience" (via History.utah.gov)

As told in award-winning journalist Nate Schweber's upcoming book "This America of Ours," the DeVotos primarily waged a political war against Senator Pat McCarran who sought to exploit the resources found on public lands in the American West. An alliance of political power and private interest would only be challenged by the DeVotos and anyone they could rally to their cause. Included in this cohort was American landscape photographer Ansel Adams, Avis DeVoto's favored publisher Alfred Knopf, and both Paul and Julia Child.

Deborah Rush played Avis DeVoto in the hit 2009 film Julie & Julia

You can rest assured that the cookbook you worked on has become a cultural phenomenon when it is the basis for a feature length film featuring Meryl Streep, Stanley Tucci, and Amy Adams. "Julie & Julia" is a 2009 film written by Nora Ephron which recreated the real-life efforts of blogger Julie Powell as she cooked all 524 recipes from "Mastering the Art of French Cooking" in 365 days. This journey also formed the basis of a book written by Powell titled "Julie & Julia, My Year of Cooking Dangerously." The film, which was nominated for an Oscar, features all the real-life individuals who played a part in bringing "Mastering the Art of French Cooking" to the market, including Avis Devoto who is played by Deborah Rush.

Speaking to foodgps.com, Meryle Streep, who played Julia Child, said she prepared by cooking from "Mastering the Art of French Cooking" and also by watching Child's numerous TV series. She did however find the earlier series more useful, suggesting that the later, more polished series did not reveal Child's character to the same degree.

As for Julie Powell, she went on to pen another book in 2009 titled "Cleaving: A Story of Marriage, Meat, and Obsession" which was widely criticized for its style, content, and execution. Linda Holmes of NPR wrote a withering review of the book as did various journalists at The New York Times.

The Childs' supported Avis DeVoto after her husband died

Bernard DeVoto's untimely death came when he was just 58 years old. He collapsed from a heart attack whilst at the television studio of the Columbia Broadcasting Company, and died at Presbyterian Hospital. For Avis DeVoto the news was devastating. Her husband who was out of town for work would never return to their home in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

In letters to her friend, Julia Child, DeVoto spoke of her grief "I don't feel shock so much as complete emptiness ... it was if he had stepped down an open manhole. I feel he just went off into space. And I feel in the most curious way cheated of all that anguish" (per Los Angeles Times). The Childs trying to help DeVoto in any way they could, sent for her to join them on a short trip to Europe. But whilst acts of kindness like these did probably help to ease the pain, it was their undying friendship that was the greatest source of comfort to Avis DeVoto, typified as always, in one of her letters to Child "Your letters help so. They all do."