The Fascinating History Behind Popular Holiday Foods

Have you ever wondered why your friends decorate their Christmas trees with garlands made with popcorn and cranberries? What about waking up on Christmas morning only to discover that Santa has mischievously stashed an orange in the toe of your stocking? Surely, Santa wasn't holding a holiday protest as a way to tell you that you need to eat more fruits and vegetables, right? And what's up with eggnog?

If you stop and think about it, the holidays have a lot of strange food traditions that no one seems to think twice about. We're not just talking about leaving cookies and milk out for a dude who's breaking into your house through the chimney, either. If you're intrigued, we're here with a little gift that consists of the unique and utterly fascinating backstories and traditions surrounding some of your favorite holiday treats. Now, at your upcoming Christmas dinner, you can proudly announce that you know why we keep subjecting one another to fruitcakes, gifting children chocolate coins, or hiding oranges in stockings.

Yule log cake (bûche de Noël)

According to Atlas Obscura, the holiday treat known as Yule log cake (also called Bûche de Noël) is a French creation based on an old pagan tradition honoring the god of lightning and thunder, Thor. Today, Yule is typically celebrated on the Winter solstice and is one of the oldest celebratory traditions in the world. And now you're invited because you're in the know.

Burning a Yule log (which is an evergreen, per the USDA) is one of the main events of this celebration. Traditionally, it was lit to convince the sun that it was worth coming back up and continuing to party for the rest of the year, per Farmer's Almanac. Way back when, families would bring a whole dang tree into their house and burn it over 12 days, starting on Christmas day.

Burning a whole tree inside a small dwelling started to fizzle out, so a single log replaced the tree. In the late 1800s, a cake began to take over. The pastry is traditionally made with sponge cake, buttercream, and chocolate frosting. Decorations are a must because it needs to look like it was lifted off the forest floor from Candy Land.

Oranges

Did you ever get an orange in your Christmas stocking and conclude that it was nothing more than cheap filler? There's a good reason it's there, however, and not just because you haven't been hitting your daily recommended dose of fruits and veggies.

Smithsonian Magazine claims that this beautiful, vibrant fruit is traditionally meant to represent gold. Now, if you're thinking that gold is typically not orange-colored, consider whether or not you want a lemon in your stocking instead. We didn't think so.

The tradition of putting oranges in your Christmas stocking can be traced back to the 19th century, when hanging stockings for Saint Nick to fill became a thing. As legend has it, the real Saint Nicolas (also the Bishop of Myra) secretly bestowed the gift of three pieces of gold by tossing them through a window or down a chimney. This monetary surprise was meant for the dowries of three impoverished young women (via "Women and Property"). The gold fortuitously landed in the stockings that were drying by the fire.

Back before modern agriculture was a thing, this tropical fruit was pretty darn expensive, so receiving one in the toe of your stocking was kind of a big deal. This sweet citrus was even known as a fruit of the Great Depression, according to Cleveland.com, because getting one in your stocking was pretty much an anomaly.

Apples

Apples are another stocking stuffer that may seem mundane but are steeped in history. The most obvious ties that the apple has to this festive holiday stem from religion, and it's not only the story of Adam and Eve stealing fruit from the tree of knowledge. During Rosh Hashanah, it's tradition to eat sliced apples with honey, per Chabad. In ancient times, the apple was linked to good health, love, happiness, wholeness, and generally being one with the world around you (via North Carolina Historic Sites). If that doesn't make you want to incorporate an apple into your daily diet, then what will?

Gift basket purveyors Pittman & Davis note that, during the Great Depression, receiving an apple in your stocking was just as welcome as getting candy, if not better. It was a symbol of hope during a time when there wasn't much of that going around (not to mention a dearth of nutritious food in some communities). This delicious fruit can also be recognized as a symbol of overall good health.

Cranberries

In the U.S., cranberries often pop up for Thanksgiving in the form of fresh and canned condiments, but they also grace Christmas dinner tables and can be elevated to home decor status. Cranberries were named by early American colonists who thought that the flowers of the plant resembled a delicate white crane foraging on the waters, per Newark Advocate. In reality, these persnickety berries should be called bog berries, since that's where they grow. Of course, calling something a bog berry doesn't have much market appeal.

According to The Independent, these floating red fruits that kind of look like miniature Christmas ornaments are harvested from mid-September to early December and only thrive under certain environmental conditions, which is why you only see them around the end of the year. As per Cornell University, ultra-tart cranberries are thought to be a symbol of kindness and abundance, which is kind of sweet if you think about it and certainly appropriate to the spirit of the holidays.

Popcorn

Popcorn isn't just for watching movies. This crunchy and versatile treat has been around in various forms for thousands of years, as noted by Popcorn.org. While it might seem like an unusual way to decorate a tree for modern folks, popped corn has been used in this manner since at least the Victorian era. It was inexpensive and pretty, reminding onlookers of freshly fallen snow. The extra perk was that you could also snack as you decorated (unless you were wearing an extra-restrictive corset, perhaps). Popcorn was also sometimes dyed a different color for a twist on the tradition.

To make your own Victorian-style colored popcorn, Lacademie says that you should put corn kernels, oil, sugar, and food dye into a pan and shake it like a Polaroid picture. Once the kernels begin to pop, cover the pan, turn the heat to medium-low, and continue to shake the pan to prevent burning. Now you too can make festive and tasty rainbow popcorn garlands! However, the most common practice for popcorn was and continues to be stringing it as-is, perhaps adding in some dried fruits or fresh cranberries to give it a bit of Christmas spirit, per Popcorn Carnival.

Chestnuts

Chestnuts symbolize goodwill and are tied to the patron saint of soldiers, tailors, winemakers, and the poor: Saint Martin of Tours (via Catholic Online). Saint Martin was a reformed soldier who was more interested in becoming a monk than harming his fellow human. The first version of his tale maintains that Saint Martin came across a beggar who had little clothing and was miserable in the cold. The soldier-monk decided to slice his cloak in two so that the beggar could have some sort of protection. In the other version, Saint Martin cuts his cloak in half and gives the remnants to a fellow soldier. This became known as the "dividing of the cloak" and is celebrated annually on Saint Martin's Day.

So, how do chestnuts tie into this heartwarming tale? It's all because the hard shell of a chestnut splits in half once it's roasted, which reminded roasters of the splitting of Martin's cloak. This nut is now a big part of Mediterranean cuisine and is also the main foodie staple at Saint Martin's Day celebrations across Europe, per Portugal Resident.

Gingerbread people

The history of gingerbread people isn't all gumdrops and lollipops, as CrimeReads notes. This baked good can be traced back to the ancient Roman celebration known as Saturnalia, per Britannica. This annual shebang coincided with the winter solstice and was held in honor of the god Saturn, who in Greek mythos is known as Cronus. Saturn was the youngest of the 12 titans who lived in fear that his children (Hades, Hestia, Demeter, Hera, and Poseidon) would usurp him. So, naturally enough, he ate them. He didn't get a chance to eat his last-born, Zeus, who one-upped him in the end and freed his somehow still-living siblings from their cannibalistic father's insides.

Romans wanted to make a good impression and appease the gods, especially during their festivals. As the story goes, Romans noshed down on gingerbread men, either in the lead-up to actual human sacrifice or in place of older, bloodier traditions. According to CrimeReads, those tasty gingerbread folks could also be consumed by Tudors looking to magically land a husband or witches seeking vengeance by chowing down on gingerbread in the shape of their enemies.

Gingerbread houses

No holiday is complete without participating in building a gingerbread house or at least seeing a seriously decked-out gingerbread dwelling. According to The Guardian, the first gingerbread recipe can be traced back to Greece around 2,400 BCE. However, gingerbread houses as we know them were a German creation that arose during the 16th century, per PBS.

By the early 19th century, gingerbread houses were already a holiday thing, but it was the Brothers Grimm and their disturbing fairy tales that boosted this architectural confection to a whole new level. In the 1812 tale of Hansel and Gretel, the cannibalistic witch lived in a gingerbread house with a cake roof and sugar windows. She should have put sugar skulls and black licorice up there, too, for an extra creep factor. Yet, it's hard to look at a charming little gingerbread house and not be reminded of the chilling fairy tale where one such building was used for a seriously nefarious purpose.

Fruitcake

Unlike some of the other holiday treats on this list, fruit brick — sorry, fruitcake — does not have dubious origins. Most every culture has some form of fruitcake, per Smithsonian Magazine. The Germans have stollen, Italians have panettone, and in Portugal, it's king cake (per The Sounds of Portuguese). The ancient Romans had their version that was filled with honey, wine, nuts, dried fruit, mashed barley, and pomegranate seeds, as per Palm Springs Life. It was meant to be consumed as a sort of energy bar on the battlefield or on the road as soldiers ventured out to conquer new lands.

This sweet and dense cake-bread-weapon combo arrived on American shores with the European colonists, who also favored using sugar to preserve and candy summer fruits so that the creation would last through the winter (via The Conversation). What are you supposed to do with a surplus of crystallized fruit and the bitter winter cold looming? Make calorie-dense baked goods, using all that sugary goodness and a good amount of alcohol to keep it preserved.

Mincemeat

Have you ever eaten a mincemeat pie? If you haven't, then surprise! There's no meat involved, though there used to be. According to Walker's Shortbread, mincemeat was born out of necessity as a way to preserve a variety of meats. There was no curing, smoking, salting, or drying necessary. Instead, cooks used finely cut meat, fruit, spices (nutmeg, clove, and cinnamon are traditional), and alcohol, per Historic UK. Mincemeat was mostly used as a pie filling.

Starting in the 11th century, tiny Christmas pies shaped like cradles (meant to look like the manger the infant Jesus used) were consumed during the 12 days of Christmas, writes What's Cooking America. King Henry VIII was also reportedly very into the mincemeat pie tradition and made sure that they were the main foodie event at his royal Christmas dinners. Over the years that followed, putting actual meat in the mincemeat pies began to become less popular, though the name stuck around.

Figgy pudding

We're sure you've heard of figgy pudding during a carol or two, but do you know what goes into the food? This sweet dessert also goes by the name "plum pudding" and "Christmas pudding", as noted by NPR, but it originally started as a way for Medieval English folks to preserve meat. Figgy pudding wasn't originally a dessert, either. According to History, it was like an early version of a sausage. Meat, grains, spices, herbs, fruit, and fat were stuffed into casings made out of animal intestines to keep the ingredients from spoiling.

Other records indicate that it was more like a hearty soup or porridge made with meat and vegetables, as per History Today. Somewhere down the line, it became more like a sinfully delicious fruit-laden cake, and by the 1600s, figgy (plum) pudding had become a Yuletide staple. Figgy pudding (along with nativity scenes, Christmas carols, and yule logs) was banned by the anti-monarchist Oliver Cromwell in 1647. However, after 50 long years without figgy pudding, George I, also known as the "pudding king," reinstated this decadent dessert and other holiday traditions previously pooh-poohed by the Puritans.

Chocolate coins

Who doesn't love getting chocolate coins at a holiday celebration? This traditional treat can be consumed on both Christian and Jewish holidays and symbolizes prosperity and good wealth. These chocolate coins used to be real money, per NPR. We're not talking money for kids, either (those would have to be some super well-behaved children). During Hanukkah, giving children gelt recalls an older form of monetary reward that was meant for hardworking laborers, like the local butcher, baker, candlestick-maker, and the guy who would pound on your door early in the morning to make sure you were getting your prayers done. These coins were basically thank you tips for these individuals.

By the end of the 1800s, the practice had morphed from the dispensation of cold, hard cash into kid-friendly chocolate. And instead of hardworking adults getting a little holiday token of appreciation, dreidel-playing kids were rewarded with sugar.

Candy canes

We've all seen what candy can do to a kid. It may keep them quiet initially, but then 10 minutes later they may seem more like tiny demons that have just escaped the underworld. Sugar has the power to both keep kids quiet and also turn them into your worst nightmare. Allegedly, the candy cane was created in the late 1600s by a German choirmaster to keep antsy choirboys from fidgeting and being, well, young boys, as per History. Those first candy canes weren't hook-shaped, nor were they made with peppermint. They were originally simple white sugar sticks.

To keep up with the Christmas spirit, the candy sticks were formed into shepherd's hooks that were reminiscent of the sheepherders who show up to worship the infant Jesus in the nativity story. According to Candy History, it wasn't until the early 1900s that the candy cane took on its red striping and peppermint flavor.

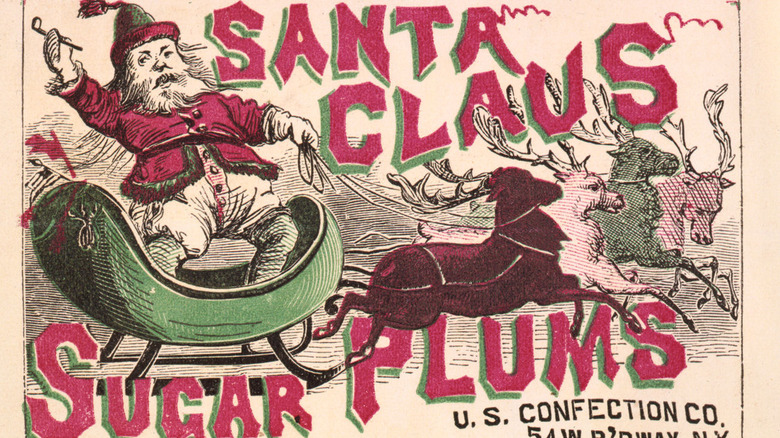

Sugar plums

A sugar plum sounds as if you're supposed to take a plum and somehow roll it in sugar. It also sounds like a good marketing ploy for the plum and sugar industry (unless you're going for a dried plum, in which case, that's great for the digestion industry). We all know candied fruit is a big deal during Christmas, but like many of the other items on this list, sugar plums are not what they sound like.

Sugar plums have medieval origins and are called comfits, per the Oxford English Dictionary (via National Geographic). These treats were just nuts, seeds, or spices (like fennel) that were coated with layers of sugar. Sugar plums are more closely related to the Easter favorite Jordan almond and less like actual candied fruit.

But what's up with the whole plum thing? According to The Atlantic, "plum" simply refers to the oblong shape of the candy. So, if you eat a sugar plum this Christmas, you won't be dancing to the bathroom late at night.

Eggnog

You're either on team 'nog or you're not. This rich, holiday drink that is beloved and reviled in equal measure can be traced back to Britain, according to Smithsonian Magazine. A form of eggnog was consumed by monks back in medieval Britain, writes TIME, though it was called posset and was more like a hot, creamy, frothy ale.

Eggnog was a popular holiday drink amongst 18th-century Americans. One thing that was in abundance at this time was livestock, like chickens and cows, and easily home-brewed alcoholic beverages. Eggnog's core ingredients are milk, eggs, sugar, and alcohol, all easily accessible and palatable to an early American farmer.

But what's with the unappetizing name? According to Forbes, the old English "grog" actually means "rum", which you would get at a tavern. Nog is the shortened version of "noggins," which isn't your cranium but rather a small, wooden serving cup. The drink was technically called "egg-n-nog" (with some grog) but you know, when you've had one too many adult beverages, the very act of speaking becomes a bit difficult.