Incorrect Things We Believed About Food 25 Years Ago

Once upon a time, we were certain the sun and planets moved around the Earth. We were confident the Titanic was unsinkable. We thought disco was here to stay and vinyl jumpsuits were the height of sophistication.

With time, however, we learned that the Earth and other planets orbit the sun. We witnessed the sinking of the Titanic. We realized that Bruno Mars is here to stay and ironic hipster T-shirts are actually the height of sophistication.

To err is human, as they say, and just as we have erred in the observatories and on the runaways, we have erred in the kitchen. It didn't take us long to figure out that certain mushrooms are poisonous and everything tastes better covered in Sriracha. But other culinary misconceptions took us longer to debunk. Over human history, we've cooked up some serious food fallacies that were accepted as truth as recently as a few years ago. Here are some culinary misconceptions we've debunked within the last 25 years.

Fat is the enemy

Meander down the health food aisles of any grocery store in the '90s, and you'd be swallowed by a barrage of fat-free products. The roots of America's war on fat can actually be traced back to the '70s, when the government first began advising the nation to nix fat in order to stave off heart attacks and weight gain.

But our fat-free frenzy went into full swing during the 1990s, when the whole country seemed to be convinced that fat was evil and carbs were good. Seizing the opportunity, the food industry starting churning out everything from fat-free SnackWell's to low-fat YoCrunch vanilla yogurt. To make these low-fat evil concoctions without sacrificing taste, food manufacturers packed in sugar, salt, and refined grains.

But while the low-fat craze raged on, Americans were, curiously, growing fatter. Turns out, a low-fat diet brought about minimal benefits, and did little to minimize our risk of obesity, heart disease, and cancer.

In fact, we now know dietary fats are key to giving the body energy, supporting cell growth, absorbing important nutrients, and all kinds of good stuff.

What else have we learned since the sugary, refined carby days of the fat-free frenzy? In moderation, foods with "good" (aka monounsaturated and polyunsaturated) fats won't make you fat — on the contrary, such fats are essential to being healthy and feeling satiated.

Chocolate is an aphrodisiac

The idea of chocolate as an aphrodisiac has been around since the ancient Aztecs, but was perpetuated through the American mainstream in the 1980s. That was when doctors at the New York State Psychiatric Institute theorized chocolate triggers the feeling of being in love because it contains phenylethylamine (PEA), which acts similar to amphetamines to create the sensation of euphoria. The idea of chocolate as an aphrodisiac was popularized in The Chemistry of Love, written by researcher Dr. Michael R. Liebowitz and published in 1984.

But subsequent research found that the amount of PEA in chocolate is negligible and too minor to have effect on sexual arousal even after copious consumption. A 2006 study found that chocolate made no significant impact on the sexual arousal of female participants. Any sexual desire that accompanies chocolate consumption is likely due to the placebo effect, most modern researchers agree.

This busted myth might help explain why romantics go scrambling to the chocolate aisle every Valentine's Day. They still tend to think it'll help them get lucky — just maybe not for scientific reasons.

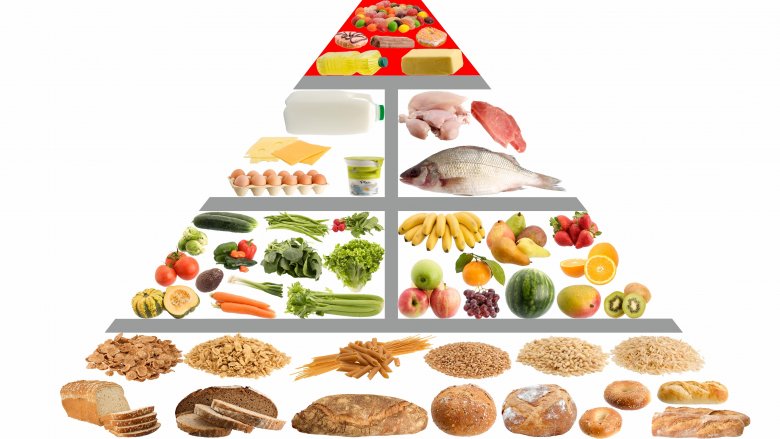

The food pyramid

How much time did you spend learning about the food pyramid when you were a kid?

The U.S. government introduced the first Food Guide Pyramid in 1992. The iconic pyramid used illustrations to highlight nutritional advice, including suggestions for variety, moderation, and proportion.

But there was one major problem with the original Food Guide Pyramid: it was wrong. The guide placed fats at the very top and carbs at the base of the pyramid, promoting the kind of low-fat diet that can actually lead to weight gain and higher levels of cholesterol. The pyramid villainized all kinds of fats and neglected the benefits of the healthy monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats found in olive oil, fish, and nuts.

The Food Guide Pyramid treated carbs with similar clumsiness, grouping all grains together without explaining the important difference between nutritious whole grains versus nutrient-lacking refined grains. The pyramid also placed healthy proteins like fish and beans in the same group as less healthy proteins like processed and red meats.

Since its initial introduction, government food guidelines have gone through numerous makeovers. Today, the USDA encourages the MyPlate model, which stresses the importance of fruits, veggies, and whole grains, while cautioning consumers against excessive sodium, sugar, and saturated fat consumption.

Cooking food wrapped in aluminum is totally safe

Wrapping meat, fish, and veggies in aluminum foil before baking or grilling has been commonplace since foil debuted in the consumer market in the 1940s. However, recent research warms consumers that cooking food wrapped with tin foil in the oven could have adverse effects on your health.

According to the Department of Health and Human Services, the human body is able to consume small amounts of aluminum without adverse effects. However, exposure to high amounts of aluminum may cause respiratory and neurological problems, including Alzheimer's disease and cognitive and neurological defects.

Researchers warn that cooking food with aluminum foil may allow unsafe levels of aluminum to seep into food. The amount of aluminum that is allowed to pass into your food may be impacted by factors like temperature and acidity and ingredients of the food you are cooking with. While further research may be merited, most experts recommend that aluminum foil be used for storage and not cooking.

Milk is the mightiest source of calcium

If you were alive in the 1990s, you probably remember the Got Milk? ads. Throughout the '90s and early 2000s, consumers were bombarded with ads from the dairy industry featuring photos of celebrities with milk mustaches captioned by the catchy tagline, "Got milk?" These ubiquitous ads touted milk as the ultimate source of calcium and an elixir for building strong bones.

Some 25 years later, the health halo over milk has faded considerably. Milk consumption in the U.S. has been steadily on the decline for the last couple of decades, while the sale of plant-based milk is on the rise. Less than 50 percent of Americans report drinking milk on a daily basis.

Behind the decline is recent research disproving many of the purported health benefits of milk. Most studies found no significant connection between milk consumption and reduction in broken bones and fractures, while others suggested greater dairy intake at a young age could be linked to a higher incidence of bone fractures.

Harvard researchers agree that calcium is beneficial, but maintain that milk is neither the only nor best source. Instead, nutritionists recommend seeking calcium from non-dairy sources like leafy green vegetables, beans, and tofu. Unlike milk, such sources have not been linked to problems like weight gain, heart disease, and diabetes.

Cereal is part of a complete healthy breakfast

After watching an ad overemphasizing the bone-fortifying benefits of milk, consumers in the '80s and '90s were likely to be hit with a commercial crowning cereal as "part of a complete breakfast." During this magical time, American audiences were taught that processed, refined carb-heavy, sugar-laden cereals like Lucky Charms and Frosted Flakes were nutritious foods to feed our children and ourselves first thing in the morning.

Technically, cereal does qualify as part of a "complete" breakfast — whatever that means. To demystify the somewhat vague concept, nutritionists have since defined a "complete breakfast" as one that includes both carbohydrates and protein. Because refined sugars technically qualify as carbohydrates, even sugary breakfast cereals are indeed "part" of a complete breakfast.

Of course, qualifying as half a complete breakfast on a technicality does not mean cereal is part of a healthy breakfast, as many consumers have realized by now. The refined sugars in many cereals cause a spike in the bloodstream, resulting in a sugar rush followed by a crash and cravings soon after. An excess of sugar in your bloodstream results in your body storing it as fat rather than using it as energy.

So what constitutes a breakfast that is both complete and healthy? Modern nutritionists recommend steering clear of processed cereals and going for complex carbs like whole wheat toast or oatmeal and healthy proteins like eggs or Greek yogurt.

Breakfast is the most important meal of the day

While we're on the subject of aggressive cereal marketing, did you know the adage "breakfast is the most important meal of the day" was perpetuated as a 1944 marketing campaign to sell cereal?

For generations, eating a meal in the morning was neither an established tradition nor essential. The Romans believed it healthier to stick to one meal per day, while the medieval Europeans saw breakfast as either a luxury for the wealthy or a necessity for laborers. It wasn't until the 1940s during World War II, when government nutritionists started backing cereal companies in their insistence that everyone ought to start their day with a breakfast, that the meal rose to a revered status. Since then, breakfast has continued to build its reputation as the most important meal of the day with the help of flawed and financially conflicted research.

Mothers everywhere used the phrase for decades to convince still-sleepy kids to choke down their morning meals, but recently, we've learned it's not as true as we thought.

Health professionals are now calling the glorification of breakfast into question. Medical research has since demonstrated that skipping breakfast does not sabotage our health, performance, or weight loss goals. When it comes to overall health, cognitive ability, and dieting, studies haven't shown any conclusive evidence that breakfast is any more important than any other meal.

Diet soda is a healthy alternative to soda

Twenty-five years ago, soda consumption was on the rise. Per capita consumption of carbonated beverages in the U.S. peaked in 1998 at 53 gallons per capita.

Since then, there has been a plethora of research linking soda to obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and other health conditions. Now, the average American consumes less than 40 gallons per year.

It was in the past decade alone that public scrutiny turned to diet soda. Up until then, diet sodas were seen as harmless alternatives to their sugar-rich substitutes, or even healthy like drinking water. Nowadays, the verdict is still out on the healthiness of diet sodas, with recent research suggesting that artificial sweeteners may result in unwanted side effects.

A review of studies on diet soda warn that artificial sweeteners could thwart dietary goals by offsetting a spike in insulin and triggering cravings for sugar and calorie-laden foods. The same report links diet soda with diabetes, heart disease, and stroke.

Over the last decade, studies have suggested that artificial sweeteners can alter the gut microbiome. This, in turn, can translate to a higher risk of diabetes and metabolic dysregulation. More research is needed to understand the true effects of diet soda. In the meantime, many experts recommend limiting or eliminating diet soda consumption whenever possible.

Fruit juice is healthy

If soda saw high rates of consumption 25 years ago, fruit juice enjoyed a elevated status as a health drink throughout the '90s. For years, the juice industry relied on their healthy image, marketing products with catch-phrases like "100 percent juice" and "fresh-squeezed." Even as schools got rid of sodas, they continued to serve children plenty of fruit juice.

Recent studies have since shown that fruit juice definitely never earned its healthy image. In fact, some juices are actually higher in sugars than soda. The high levels of fructose sugar found in fruit juice aren't easily consumed by the human body, which converts fructose into fat. This, in turn, increases risk of obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and other problems.

Today, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that parents not serve fruit juice to children under the age of 1 and severely limit fruit juice consumption for older children. For us grownups, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends limiting sugar intake to five percent of your total daily calories. For most adults, that's around 25 grams, which is less sugar than contained in one eight-ounce serving of popular fruit juices like Ocean Spray 100% Cranberry Juice (28 grams) and Mott's Apple Juice (28 grams).

Turkey makes you sleepy

After gobbling down a hearty Thanksgiving meal, you may inevitably find yourself dozing off on the couch during the post-meal football game. Thanksgiving after Thanksgiving, we attribute our post-meal sleepiness to the tryptophan found in turkey. This amino acid is a part of the brain chemical serotonin, which can cause feelings of calmness, relaxation, and sleepiness — in the right context.

As myth-busters have since explained, turkey contains about the same amount of tryptophan as chicken, lamb, and beef, and less than Swiss cheese or pork. Turkey and other poultry and meats may contain tryptophan, but they also contain other amino acids that prevent tryptophan from reaching the brain and increasing serotonin levels. So what's behind the sleepy feelings following a Thanksgiving meal?

Science attributes much of the post-T-giving meal drowsiness to carbohydrates, which trigger the release of insulin and allows tryptophan to enter the brain to form serotonin more easily. This means that chowing down on carbohydrates with any tryptophan-rich foods can spur sleepy feelings. Research has also found that eating larger-than-normal amounts of food can tire out the brain, as can consuming the large amounts of booze most of us end up consuming when seated at the table with our Crossfit-obsessed uncle.

Gum stays in your system for seven years

It was the word on the playground during many of our childhoods: Don't swallow chewing gum because it stays in your system for seven years. Though its origins are unclear, the time-honored adage has managed to wedge itself into our subconscious, sounding a warning bell every time we accidentally swallow gum.

In the last couple of decades, various medical journals and academics have challenged the claim that gum takes seven years to pass through the digestive system. Gastroenterological experts agree that the body may pass chewing gum through the digestive system at a slower rate, but eventually pushes the gum through the small intestine, into the colon, and out as stool — usually within a manner of days.

Health professionals do concede that in rare cases, swallowing a large quantity of gum over a short time period could create a large, indigestible mass known as a bezoar. Made when foreign objects like hair and seeds clump together with sticky substances like gum, bezoars form in the stomach or gastrointestinal system and cause problems like constipation or abdominal pain. So maybe don't go around swallowing big wads of gum constantly, but don't freak out if you accidentally swallow a piece while smooching your sweetie — it won't stick with you for the next seven years.

You should wait 30 minutes after eating before swimming

Here's another medical myth you might remember from your childhood: you should wait 30 minutes to swim after eating. According to the legend, blood would be redirected to your digestive system after you were eating, diverting it away for your arms and legs. Deprived of blood flow in your limbs, you might have trouble swimming and become more easily fatigued, thus putting yourself at a higher risk for drowning.

Within the last couple decades, the rumor has been discredited by medical professionals, who generally agree that the claim has little basis in science. Although the body may divert blood flow from arm and leg muscles to aid in digestion, enough typically remains in the entire body to keep everything running during the process.

As with any strenuous exercise on a full stomach, you might experience heartburn and minor muscle cramping after swimming. But beyond from minor discomfort, there is no real danger attributed to swimming right after eating.