The Untold Truth Of Pop Rocks

In the pantheon of candy, it's doubtful that any sweet treat has benefitted more from scientific experimentation than Pop Rocks, the iconic candy that became famous and ultimately notorious for creating tiny "explosions" inside kids' mouths. Introduced to an unsuspecting market way back in 1974, children of the era couldn't get enough of this carbonated confection that amazingly simulated the feeling of fireworks going off inside one's skull.

With an origin that actually extends all the way back to the 1950s, Pop Rocks have been the source of scandal, urban legends, parental fear, and damage-control public-relations campaigns. In fact, it's not hyperbole to say that Pop Rocks may well be the most misunderstood commercially produced candy ever.

Despite the product's long history and enduring popularity with the younger set, how much do candy connoisseurs really know about this wholly unique candy creation? Keep reading to discover some truly fascinating facts by taking a deep dive into the untold truth of Pop Rocks.

The invention of Pop Rocks was an accident

According to an exhibit at Vancouver's Science World, the Pop Rocks story began in 1956 when General Foods chemist William A. Mitchell was experimenting on creating an instant soft drink.

"We were trying to make a carbonated beverage powder that would taste good," Mitchell said in an interview with People. As Mitchell explained, what he was working on was a drink powder that, when mixed with water, would transform into a fizzy carbonated drink. "We wanted to put carbon dioxide directly into a solid," he said.

The resulting carbonated powder didn't work the way he had hoped, but when he tasted a bit of it Mitchell quickly realized he had stumbled onto something interesting: sweet little chunks that would "pop" when placed inside the mouth, the carbon dioxide activated when the heat and moisture of saliva dissolved the chunks. As People noted, scientists from all over the company came to Mitchell's lab to sample his inadvertent creation.

"It became a game — who could swallow the biggest chunk," Mitchell recalled. "It was a fun afternoon and we wasted a lot of time, but I thought it was a good thing from the start."

The inventor of Pop Rocks also invented Jell-O, Tang, and Cool Whip

Pop Rocks was far from the only food product to spring from the inventive mind of William A. Mitchell. As Smithsonian Magazine recalled, Mitchell was also responsible for some of the most iconic items found on supermarket shelves during the 1950s and 1960s

It was back in 1957, in fact, that Mitchell invented a Day-Glo orange-colored flavored crystal that, when mixed with water, turned into a faux orange juice, dubbed Tang. Tang made history when it was taken into space by astronauts, used to disguise the metallic taste of the water aboard NASA spacecraft. Astronaut Buzz Aldrin drank it during his famed space missions, but wasn't a fan, telling NPR years later that "Tang sucks."

A decade later, Mitchell hit a double home run when, in 1967, he patented a powdered gelatin that would set with water, which General Foods would later turn into quick-set Jell-O. He followed that up the same year with a non-dairy whipped cream alternative called Cool Whip, which was so embraced by consumers that it quickly became its division's most profitable product.

What makes Pop Rocks pop?

Equally as fascinating as the accidental invention of Pop Rocks is the science behind why this unique candy pops when placed in one's mouth. According to the patent, explained Science World, the mixture is heated to 280 degrees Fahrenheit, at which point carbon dioxide is added under pressure of 600 psi (which is about half the pressure used in soda). When the mixture cools and the pressure is released, the resulting concoction hardens and then shatters into tiny pieces. Those small fragments are filled with tiny bubbles of carbon dioxide.

When the resultant candy is placed in the mouth, the heat and moisture causes the candy to dissolve, leading those tiny gas bubbles to burst and make the distinctive popping noise, while creating a tickling sensation within the mouth.

Pop Rocks creator William A. Mitchell is an admitted fan of his candy invention. "Oh man!" he excitedly told People when describing the sensation of popping some Pop Rocks into his mouth. "It snaps, it fries — you don't know where it's coming from!"

Will mixing Pop Rocks and soda make your stomach explode?

One of the most prevalent beliefs associated with Pop Rocks is that the candy is actually dangerous — as in, lethally dangerous. As Snopes recalled, an urban myth took hold as early as the 1970s, declaring that some child somewhere scarfed several bags of Pop Rocks in combination with soda and died after his stomach swelled with gas and then exploded. That, of course, never happened, yet the unfounded rumor spread far and wide, leading many people to believe that Pop Rocks were downright deadly.

"There is no danger," Pop Rocks creator William A. Mitchell assured People. "The worst thing the rocks could do is make you burp. The amount of gas in Pop Rocks is less than one-tenth the amount in a can of soda pop."

In fact, an episode of Discovery's Mythbusters successfully disproved the claim that Pop Rocks and soda would make one's stomach burst. After testing it out with an elaborate experiment involving a pig's stomach, hosts Jamie Hyneman and Adam Savage ultimately concurred with Mitchell's claim about the burping, but concluded the Pop Rocks-soda combo simply didn't produce enough gas to fatally explode a human stomach.

Did Pop Rocks kill TV's Mikey?

At some point in the 1970s, the urban legend that drinking soda in combination with Pop Rocks was killing children en masse morphed into a bizarre apocryphal rumor that was spread during recess in schoolyards throughout the country. This rumor claimed that a familiar TV personality met his end by eating Pop Rocks and washing it down with soda.

In 1971, Quaker Oats produced a now-iconic commercial for its Life cereal, featuring some dubious kids who thought the cereal looked too healthy to be any good. They decided to first test it on little Mikey — who "hates everything" — to gauge his reaction. Mikey happily gobbled it up, spawning the catchphrase "Mikey likes it!" Several years later, a rumor circulated that the boy who played Mikey was the child who was killed by combining Pop Rocks and soda.

That was nonsense. The actor who played Mikey, John Gilchrist, did not die. In 2012, he told Newsday that he first heard of the rumor in the late 1970s, when his mother received a tearful call from a friend offering her condolences that her son had been killed by candy. "He just came home from school," Gilchrist's mom told the friend.

General Foods took extreme measures to combat the dangerous Pop Rocks rumors

The urban legend that Pop Rocks were slaughtering America's children spread like a virus, and became so prevalent that General Foods was forced to take some extreme measures. In 1979, notes an FAQ on the Pop Rocks website, the company took out a full-page ad that it ran in 45 major publications throughout the country to let consumers know the rumors were bogus and that Pop Rocks were completely safe.

In addition, the company also delivered around 50,000 letters to school principals all over the U.S., and even sent Pop Rocks creator William A. Mitchell on a speaking tour to do some damage control by personally explaining the ins and outs of his candy to terrified parents in order to assuage their fears.

Controversy and Pop Rocks, it seems, were never far apart. Even before the rumors of exploding stomachs started circulating, parental concerns over the noisy treat had grown to the point that the FDA set up a hotline to inform parents that the candy popping away like tiny fireworks in their children's mouths was perfectly safe.

How Pop Rocks can blow up balloons

While Pop Rocks mixed with soda may not be lethal, the combination does indeed produce an excessive amount of gas. And while the amount of carbon dioxide expelled may not be enough to actually kill someone, it is enough to blow up a balloon.

West Virginia CBS affiliate WDTV demonstrated a simple science experiment utilizing a bottle of soda, some Pop Rocks, a balloon, and a funnel. The instructions were as simple as it comes: pour a packet of Pop Rocks into the balloon by using a funnel, fasten the balloon to the top of the soda bottle and then pull the balloon up in order to drop the Pop Rocks into the soda.

At that point, the Pop Rocks become coated in bubbles, with gas escaping from both the soda and the candy. As the gas escapes, it has nowhere to go except up into the balloon, filling it up with gas and causing the balloon to expand.

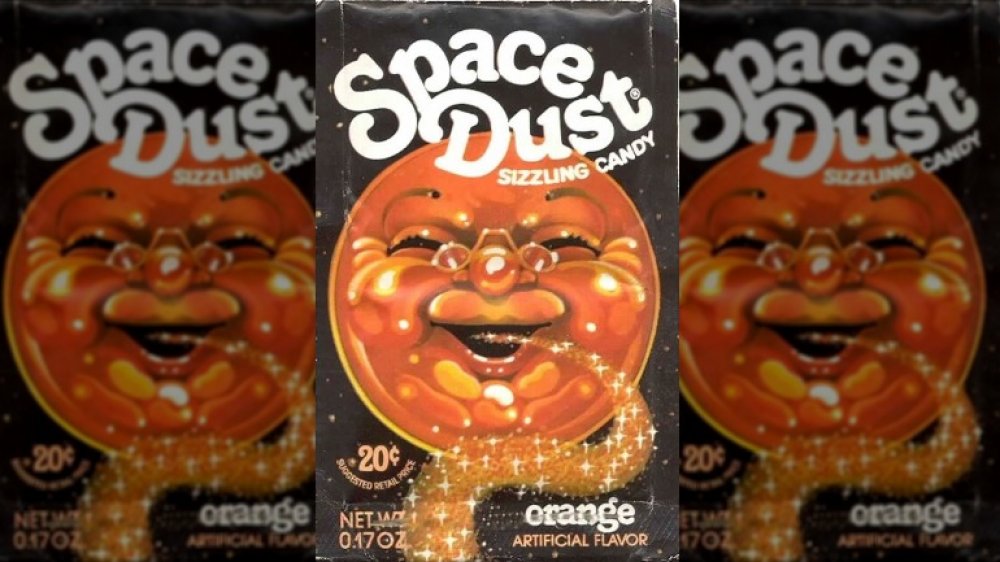

A Pop Rocks spinoff did not take off

Despite the real controversy generated by fake rumors, Pop Rocks continued to be a hit with kids, who possibly experienced the thrill of cheating death whenever they tossed some into their mouths. That was why, recalled the Gone But Not Forgotten Groceries blog, in the late 1970s General Foods decided to launch a spinoff product. Dubbed Space Dust, this candy was essentially Pop Rocks that had been crushed into a fine powder.

The title turned out to be an unfortunate one. At the time of the new candy's debut, noted the blog, powder-based drugs such as cocaine and heroin were experiencing a surge in poularity. Worse, a mind-altering drug name Phencyclidine, also known as PCP, had been making headlines when those who took it went berserk, hallucinating and often engaging in violent behavior. That drug's street name: angel dust.

The similarity in nomenclature between angel dust and Space Dust caused even more parental fears, driving down sales to the point that General Foods rebranded the product under a new name, Cosmic Candy, in order to remove the impression it was selling some kind of drug to unsuspecting children. The product was eventually discontinued.

Pop Rocks made a surprising comeback in cocktails

Pop Rocks were once popular in school playgrounds, but in recent years the candy has been making a comeback in an unexpected location: behind the bar. In fact, creative bartenders have been using Pop Rocks in cocktail creations utilizing the candy's fizzy little explosions in their libations.

One online recipe detailed how to create Jell-O shots with Pop Rocks, combining two products invented by General Foods scientist William A. Mitchell in a way he likely never anticipated. Meanwhile, candy-loving cocktail connoisseurs can enjoy another inventive treat, the candy corn vodka martini with Pop Rocks on the rim of the glass (anyone attempting this cocktail, however, is reminded to ensure the Pop Rocks don't get wet ahead of serving, because wet Pop Rocks won't pop).

There are even non-alcoholic beverages utilizing Pop Rocks, such as Pop Rocks punch, a mixture of fruit juices with Pop Rocks sprinkled atop just the drink is served. For an additional jolt, the rim of the glass is coated with Pop Rocks, margarita-style.

Chefs have been using Pop Rocks, too

Pop Rocks aren't just finding their way into cocktails, but also into food. In fact, numerous chefs at some of the world's top restaurants have used the candy as an ingredient in some of their more unusual dishes. For example, a 2000 article in the Washington Post described chef Christy Velie using Pop Rocks in a mushroom ceviche served at the Washington, D.C. eatery Cafe Atlantico. "We want to change people's dining experience," she told the Post. "We want them to be entertained at the same time."

In fact, Food Republic listed 30 other chefs were utilizing Pop Rocks in their dishes in 2014, and some of those were in some wildly creative ways. Among them were a sushi roll coated with watermelon-flavored Pop Rocks from Nashville's Virago restaurant and a foie gras lollipop encrusted with Pop Rocks from celebrity chef Graham Eliot's namesake Chicago restaurant.

Atlanta restaurant Poor Calvin's Absolute Fusion, noted Food Republic, offered two menu items featuring Pop Rocks: a lobster tail coated with Pop Rocks and a duck pate served with a red-wine-lavender jelly and Pop Rocks.

A celebrity chef thinks Pop Rocks make a seductive sound

Another chef who uses Pop Rocks in recipes is Heston Blumenthal, a pioneer in the molecular gastronomy movement whose restaurant, The Fat Duck, infuses science in its dishes. Blumenthal has demonstrated a fondness for Pop Rocks as an ingredient. According to Heston, the enjoyment of food isn't based simply on how a dish tastes, looks and smells, but also on how it sounds.

In his series Heston's Recipes for Romance for Australian TV network Lifestyle Food, Blumenthal shared his theory that Pop Rocks aren't just fun, but also seductive. To prove his point, he brought in physicist Oliver Joseph to survey diners as they listened to an array of "chewing, scraping, biting and sucking noises," asking them to rate the sounds they enjoyed the most.

"One of the sounds the subjects consistently liked was the popping candy," Joseph told Heston. '[It's] sort of rhythmic, in some sort of comforting way, maybe a bit musical and of course it is being done by a mouth so it is something a little like singing."

Perhaps that was one of the considerations when he created his exploding chocolate gateau, using Pop Rocks as the explosive secret ingredient. Maybe he thinks the surprise of the base exploding in their mouths with work as an aphrodisiac?

Pop Rocks featured in a lawsuit between two chefs

In 2011, the New York Post reported a bizarre lawsuit launched by Jehangir Mehta, owner of Graffiti Bistro & Bakery in New York City's East Village, who sued chef Jesus Nunez Rabano over accusations that Rabano ripped him off when he opened his similarly named Graffit USA on the Upper West Side. It wasn't just the eatery's name that was at issue, however; Mehta also accused Rabano's restaurant of stealing his "unique food combinations and unusual ingredients."

The key ingredient mentioned in the trademark-infringement lawsuit was Pop Rocks. As Mehta's suit pointed out, he'd been using Pop Rocks as a recipe ingredient "for many years" in his restaurant, and also utilized the candy when he competed in the Food Network's The Next Iron Chef, in which he was a runner-up in 2009.

According to Mehta's lawsuit, he learned of Rabano's alleged culinary thievery "as a result of an interview given by Nunez" in which he revealed that the "defendants also planned to utilize this extremely obscure ingredient in a dish to be served at Graffit."

Taco Bell used Pop Rocks (or something like them) in a burrito

High-end restaurants aren't the only eateries utilizing Pop Rocks as a recipe ingredient. In fact, at least one fast-food chain got in on the action when, in 2017, Taco Bell introduced its Firecracker Burrito. The secret ingredient, noted fast-food blog Brand Eating, was a small packet of "cayenne popping crystals" that a diner could sprinkle atop the burrito to provide a firecracker-like effect when eating it. While the Pop Rocks brand name was never used, anyone who ate the burrito knew exactly what those "popping crystals" were trying to be.

According to a report in USA Today, Taco Bell's Firecracker Burrito was offered in two varieties, "Popping Cheesy" and "Popping Spicy." At the time, the chain was testing out the Firecracker Burrito at four Taco Bells in California's Orange County, two in Santa Ana, one in Anaheim and another in Tustin, with plans for further testing at some locations in Toledo, OH.

Given that Taco Bell's Firecracker Burrito didn't move beyond the test phase and never received a national launch, it's safe to assume consumers weren't taken by the burrito and its "cayenne popping crystals."

There are recipes for homemade DIY Pop Rocks

When most people get a hankering for Pop Rocks, they simply go to the nearest purveyor of candy and pick up a pack or two. However, there are also some intrepid culinary adventurers who've attempted to make their own DIY versions, some even posting their recipes online.

In recipes shared by The Daily Meal and Saveur, the secret ingredient isn't carbon dioxide, but citric acid, which Saveur says produces an "effervescent feel on your tongue." While these recipes offer an approximation of Pop Rocks, they pale in comparison to the real thing. That's because creating actual Pop Rocks requires 600 psi of high pressure, something you're not going to get with a store-bought pressure cooker.

A video shared by Bon Appetit features pastry chef Claire Saffitz attempting to create "gourmet Pop Rocks," addressing the pressure issue by discussing adding a carbon dioxide tank to a sealed chamber in order to achieve the required 600 psi. One of the participants in the endeavor pretty much summed up the experience of making DIY Pop Rocks when he quipped, "Look, it's not gonna be easy. It's not gonna be safe. But I do think it's possible." Saffitz, however, felt the danger was too great and went with safer versions using citric acid and even dry ice.

Pop Rocks can be used in science project volcanoes

Beyond their use in cocktails, exploding cakes and Taco Bell burritos, Pop Rocks can also be used in that most iconic of school science projects: the erupting volcano.

The tried-and-true science-project volcano combines vinegar, baking soda, and red food coloring to produce a foaming "eruption" that mimics molten lava flowing from an active volcano. The Growing a Jeweled Rose website takes things to the next level by cleverly adding Pop Rocks to the mix. This, the site explained, also gives the faux volcano audible tiny explosions, adding the element of sound to the eruption — something that the chemical reaction created by mixing vinegar and baking soda doesn't provide.

The site suggests mixing a half-pack of Pop Rocks with a half-cup of baking soda, along with a full cup of vinegar. According to the experiment, the popping noises created by the Pop Rocks were both impressive and long-lasting, with the "explosions" heard for "a few minutes."

No, Pop Rocks won't hurt you

Okay, so we know Pop Rocks won't make your stomach explode, but can the candy hurt you in any other way? The answer, again, is a resounding no. Other than maybe helping cause cavities, Pop Rocks are completely safe to eat (via CandyFavorites.com).

If you're not convinced, a quick look at the food label should alleviate your fears. Pop Rocks are made up of ingredients you likely consume on a regular basis: sugar, lactose, corn syrup, artificial flavor, artificial color, and carbon dioxide. This last ingredient is key. Carbon dioxide is the secret component that makes Pop Rocks pop ... while also making people nervous about the physical harm they might experience after eating the candy. But don't worry — carbon dioxide won't hurt you. In fact, this ingredient is commonly used throughout the food industry, most notably in the production of carbonated beverages (via Globe Newswire). And Pop Rocks contains significantly less-potent CO2 than any bubbly drink. In fact, according to Food Republic, the candy's carbon dioxide is only 10-percent of that found in an average carbonated beverage.

Pop Rocks were discontinued in the 1980s

Although the rumors of Pop Rocks' ability to burst stomachs were entirely baseless, they had a crippling effect on sales of the candy. According to the Associated Press, 500 million packets of Pop Rocks were sold in the United States during an 18-month period in the late 1970s. Once the rumors started circulating, however, sales nosedived, and manufacturer General Foods experienced a 24-percent drop in profits in the final quarter of 1979. The situation got so bad that the company went ahead and discontinued production of Pop Rocks in the U.S. the very next year.

Fortunately for candy fans, Pop Rocks wasn't gone for too long. In 1985, two investors purchased the rights to make and sell the candy. They established a new company, Carbonated Candy Ventures, set up a manufacturing facility in Buffalo, N.Y., and by 1986, Pop Rocks was back on the shelves.

Clearly, people missed their exploding candies. Just a few months into business, Carbonated Candy Ventures had already shipped 1 million packets of Pop Rocks. Many of its customers were high school and college-aged individuals, who remembered the candy fondly before it went on hiatus. ″They are probably going to pick it up for old time's sake,″ Mary O'Brien, the company's vice president and general manager, told the Associated Press at the time. ″But eventually they're going to take it home and little brother and sister are going to get it.″

There are limited-edition flavors and other Pop Rocks varieties

By now, we're all familiar with the classic Pop Rocks flavors like Original Cherry, Green Apple, Strawberry, Watermelon, and Blue Razz. But that's just the start of the wide range of Pop Rocks varieties available today.

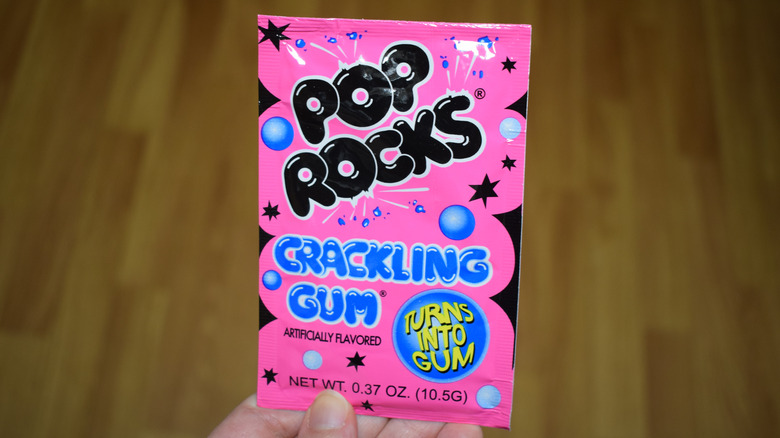

Let's start on the flavor front. In addition to its standard offerings available year-round, Pop Rocks regularly sells three, limited-edition flavors: Chocolate, Pumpkin Patch Orange and Candy Cane. That's not all — Pop Rocks are also available in different forms. There's Pop Rocks Crackling Gum, which turns into chewing gum while it crackles in your mouth, and Pop Rocks Dips, which come with a lollipop you can dip into the packet of candy (instead of pouring it straight into your mouth). And last, but certainly not least, is Pop Rocks Xtreme. As the name suggest, this variety delivers stronger flavor and a more intense — and louder — popping sensation to your tongue. Pop Rocks Xtreme is sold in a 48-count, bulk package. That should be enough to hold you over until the mad candy scientists come up with something even more extreme.

Each batch of Pop Rocks is rated for its poppy-ness

Few culinary experiences would be more disappointing than pouring a packet of Pop Rocks into your mouth only to find that the rocks do not, in fact, pop. Fortunately, the makers of the exploding candy work hard to ensure this never happens. According to Science World, as part of the process in making gasified candy, a panel of experts rates each batch of Pop Rocks on how well it pops. The candy is given a grade on a scale from 0 to 14, with 0 representing no popping at all and 14 a full-blown explosion. Any batch given a grade below 7 is thrown out.

While it may sound like a funny process, this step is taken seriously. In fact, it's even included in the patent for making Pop Rocks. That patent, awarded in 1981 to the candy's original manufacturer General Foods Corp., sheds a little more light on the process. The testing panel bases its "Pop" rating on the candy's "organoleptic quality," a fancy way of referring to the effect it has on your senses. A rating between 7 and 9 is regarded as acceptable, while a score of 10 to 12 is outstanding.

The Pop Rocks website suggests other uses for the candy

When you think of versatile foods, kitchen staples like potatoes, rice, and eggs likely come to mind — items you can either prepare a million ways or add to an extensive number of dishes. Pop Rocks, on the other hand? Probably not so much.

But the makers of Pop Rocks would beg to differ. According to them, Pop Rocks can add a pop of flavor — and surprise! — to a number of dishes. They suggest combining the exploding candy with items like cereal, ice cream, yogurt, chocolate, and baked goods.

But it doesn't stop there. In fact, it doesn't even stop at the kitchen. The Pop Rocks' website also lists a number of potential household uses for the crackling confectionary. The most compelling suggestion it provides is to add Pop Rocks to your favorite bath salts and soap bombs. We guess that's one way to get a tingling sensation all over your body!