The Essential Cooking Tool That Kept Revolutionary War Soldiers Fed

Back in the Revolutionary War days, George Washington calculated the yearly food needs for the Continental Army, and the results were staggering: roughly 20 million pounds of meat plus 100,000 barrels of flour. This is an incredible amount of food, but how was it prepared in the 1700s? Long before the days of the ready-made, vacuum-sealed meals soldiers frequently eat on modern battlefields, a single device helped soldiers prepare food during wartime: the camp kettle.

Camp kettles were distributed at a ration of one kettle to six soldiers. Fashioned from tin or sheet-iron, camp kettles held nine quarts and weighed only two to three pounds. Set over hot coals, kettles allowed soldiers to cook food using methods such as steaming, boiling, and broiling. Oftentimes, coals were placed on top of kettle lids, especially when baking bread, which helped keep heat steady and evenly distributed. The lid itself could be turned upside down to create a makeshift griddle.

While camp kettles certainly helped keep the army fed, they had their downsides. Soldiers were responsible for carrying their own kettles. While lightweight, carrying kettles for miles across rugged terrain could become cumbersome, so much so that soldiers sometimes discarded their kettles in frustration. In his memoirs, Private Joseph Martin recalled abandoning his kettle after carrying it for miles and finding no volunteers to share the load. Upon arriving at camp, he found other soldiers had done the same.

How did Revolutionary War soldiers eat?

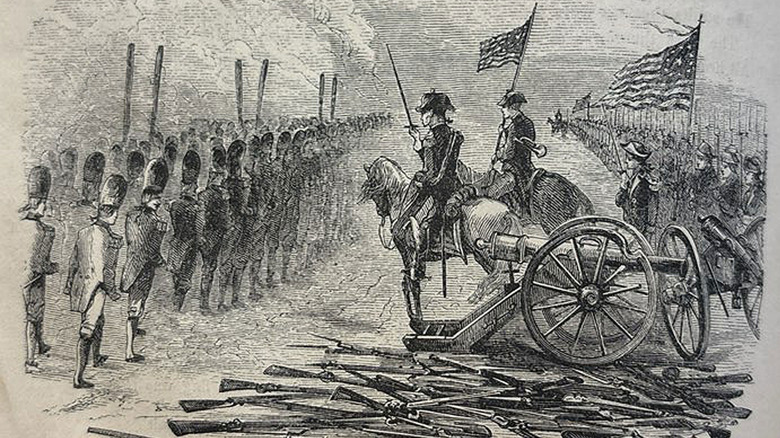

Feeding soldiers during the Revolutionary War was an uphill battle, both due to technological limitations and the Continental Army's developing nature. The army's commissary department was as new as the budding nation, and had yet to establish many of the weird rules the army has about food today. Soldiers were granted basic daily rations consisting of set amounts of meat, bread, milk, and any available vegetables and fruits. However, providing this food did not always go as planned.

Provisions often rotted, so soldiers sometimes resorted to foraging, hunting, and going door-to-door asking for spare food. Given it was difficult to preserve food in the 1700s, roughage was often limited to seasonal fruits and vegetables. Even when food was fresh, preparing it was something of a headache. With no on-site kitchen or dining hall, soldiers typically designated one cook per group of five to eight. The cook often bore the brunt of the blame for small rations and poor-quality meals, so it was a burdensome position to take on.

However, the news was not all bad for the Continental Army. While as much was unknown at the time, the camp kettle ensured soldiers opted for more nutritious cooking methods. Steaming and boiling vegetables keeps food at lower temperatures. Less heat generally helps foods retain their natural nutrients, with steaming an especially healthy choice. So, the camp kettle helped soldiers make the most out of the small amount of food they had.