Coca-Cola Products That Were Massive Fails

The Coca-Cola brand is arguably one of the world's most popular and recognizable companies. According to an article published on CNBC's Make It, Coke made just $50 during its debut year in 1886, but grew to sell almost $32 billion worldwide in 2018, with products available in 200 countries. As competition in the beverage market continues to grow, and with consumer preferences constantly changing, the only way to stay on top is to embrace innovation and to make adjustments with the changing times.

The problem? Innovation and change are rarely guarantees for success. Just because a brand is popular and well-known doesn't mean that every product they introduce to market will be embraced by consumers. And fearing failure — fearing detrimental sales, and the immense cost of advertising and marketing a new product only to have it pulled from shelves — can lead to stagnation in innovation among company leaders.

Coke's company-wide solution for encouraging innovation is to offer the Celebrate Failure Award every year — they literally reward leaders who introduce a product to market, only to have it fail. And man, oh man, have they had some massive product failures over the years. It's refreshing when you think about it — even with a slew of failures, Coca-Cola continues to thrive and grow. They do so by learning from their failures. It's a lesson worth taking to heart.

These are some of the Coca-Cola products that were massive fails.

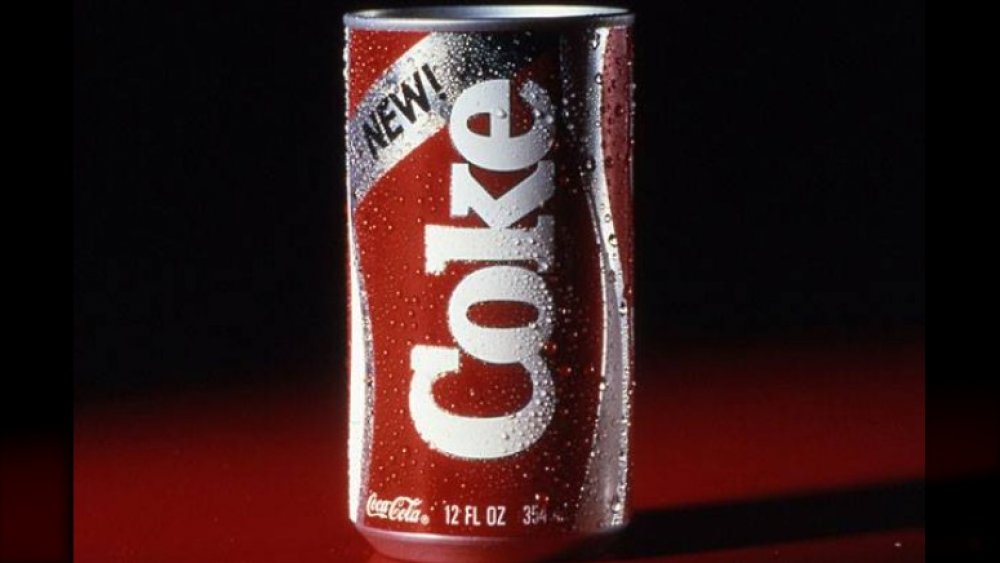

New Coke

New Coke is practically the poster boy for product failures, and according to the article on CNBC's Make It, it's actually the reason Coca-Cola offers its annual Celebrate Failure Award. In 1985, in an effort to boost sales and "refresh" its classic soft drink, Coca-Cola retired its tried-and-true recipe and introduced a new formulation, "New Coke." But according to a CBS News article, what the brand hoped would be met with cheers from fans, was instead met with a public outcry in the form of protests, petitions, and phone calls. Less than three months after New Coke was launched, it was pulled from shelves and replaced, once again, with the classic formulation (hence, the reason Coca-Cola is now Coca-Cola Classic).

In a lucky twist for Coca-Cola, when New Coke was ditched for the original version, fans rejoiced, flocking to the stores to buy more. Sales, ultimately, received a boost and Coca-Cola returned to being the number one soda brand, ousting PepsiCo, which had taken the top spot temporarily.

Dasani (in the UK)

Dasani water may be a staple on grocery store and mini-mart shelves throughout the United States, but for a global brand like Coca-Cola, just because a product works well in one location, that doesn't mean it will work well worldwide. That's certainly what happened when Coke tried to introduce Dasani in the United Kingdom. The blunder was two-fold. First, according to an article in The Guardian, this "filtered water" wasn't from a crystal-clear spring in the mountains of an unkissed tropical forest, but rather from a tap in Sidcup, southeast London. When people in the UK realized they were, essentially, being sold tap water — you know, water they could access with a turn of a knob — they scoffed at the thought of paying for such a thing.

Second, Coke was marketing the water as "bottled spunk." In the United States, "spunk" may mean spirit, courage, or determination, but in the UK? It's a slang word for semen. Not exactly a well-planned marketing ploy good for boosting sales of water. In less than a year, Coca-Cola discontinued selling Dasani in the United Kingdom, and for many, it remains as a running joke for how it's possible to butcher introducing a new product to market when you lack the appropriate knowledge of the culture where you're introducing it.

Tab Clear

The history behind Tab Clear is actually a little bit of counter-marketing genius. According to an article in Mental Floss, Coca-Cola actually intended its 1992 release of Tab Clear to fail — the product's sole purpose was to derail the launch and possible success of rival-company PepsiCo's release of Crystal Pepsi.

You see, in the early '90s, clear drinks were all the rage, but there weren't any colas on the market with the crystal-clear look. When PepsiCo decided to launch Crystal Pepsi, the idea was to offer a full-flavored (full-calorie) drink to the public, but without the dark tint so popular with other colas. Tab Clear was Coca-Cola's solution — Tab Clear was a calorie-free diet soda intended to taste like other popular colas (similar to Pepsi and Coca-Cola), but without coloring and with the stigma of being "diet." When it was released ahead of Crystal Pepsi, the intent was to blur the lines and confuse customers just enough to detract from sales of Crystal Pepsi. Crystal Pepsi wasn't a diet soda (although there was a diet version), but if it was perceived as being equal to Tab Clear (a diet soda), it was possible fewer people would buy it. Add to that the fact that Coke was convinced the clear-drink trend would fizzle out, and it was worth sacrificing Tab Clear to prevent PepsiCo from having a successful product launch.

Within a year, Crystal Pepsi and Tab Clear were kicked to the curb. Product failure = success.

Sprite Remix

Sometimes drinks with a popular fan base simply don't make financial sense for companies to continue producing long-term, and that's exactly what happened with Coca-Cola's Sprite Remix. The original Tropical-flavored drink was released in 2003, and according to an article on Business Insider, its initial success led to the addition of two more flavors — Aruba Jam and Berryclear. Unfortunately, its diehard following wasn't large enough to last more than a few years, and Coke killed production in 2005.

That said, sometimes failures with a solid following can lead to future, albeit temporary, successes. Coca-Cola seemed to take a note out of McDonald's playbook in 2016 when it decided to do a limited-time release of Sprite Remix Tropical, not unlike McDonald's famed limited-time releases of the McRib sandwich, which has a cult following. Fans were able to pick up their tropical-flavored soda temporarily, and with any luck, Coca-Cola will decide to do another limited-time release in the future.

Coca-Cola Blak

Coca-Cola Blak — a coffee-flavored Coke released in the United States in 2006 after its initial introduction in France — may have been a drink introduced before its time. At least, that's what Nancy Quan, the company's Chief Technical Officer, told CNN Business in 2019. Or, it could be that its U.S.-formulation using high fructose corn syrup and aspartame as sweeteners wasn't quite as appealing as its international version that used regular sugar. Either way, this sweet coffee drink that supposedly tasted a bit like coffee-flavored candy didn't last two years in the U.S.

That said, Coke hasn't given up on trying coffee-flavored sodas. In 2019, after promising sales in other countries, including Australia and Spain, the company is considering "bringing back" Coca-Cola Blak, albeit under another name — Coca-Cola Plus Coffee. The main differences, other than the packaging, are that the new version includes more coffee and a higher quantity of caffeine than regular Coke. Hopefully, another difference would be its long-term success.

Vault

With the rise in popularity of energy drinks in the early 2000s and 2010s, especially with PepsiCo's Mountain Dew positioning itself as a champion of extreme sports like snowboarding and skateboarding, it was just a matter of time before Coca-Cola responded with its own hybrid energy/soft drink. According to Business Insider, the 2005 release of Vault was Coke's direct answer to Mountain Dew, even using a citrus flavor and green packaging to draw consumer interest. Likewise, when PepsiCo added to its Mountain Dew line with Mountain Dew: Code Red, Coca-Cola played along, sending Vault Red Blitz to stores in 2007.

And while Vault ended up having a longer lifespan than many other failed products, ultimately sales couldn't continue justifying the cost of production. After six years of moderate success, Coke pulled the plug on the drink. That said, with its popularity being greater than most failures, there's always a chance that Coke could decide to offer the drink again on a limited-time basis in the future.

OK Soda

If you were a teenager of the '90s, there's a good chance you remember the release of OK Soda in 1995 — and there's an even better chance you were a fan. It's possible you were won over by the marketing more than the taste of the product, which, as Business Insider points out, was pretty much Coke's strategy — they were hoping to appeal to the more disillusioned and "emo" teens and young adults who were also fans of TV shows like MTV's Daria and ABC's My So-Called Life. Maybe it had a good flavor, maybe it didn't. We honestly don't remember, but the black, white, and red cans featuring bold artwork still stand out in our minds as the reason we kept grabbing them off the shelves of the local mini-mart.

It was clear very quickly, though, that OK Soda wasn't fit for a nationwide release, and sales weren't strong enough to maintain a presence in the limited markets where it was originally sold. By 1997, OK Soda had completely disappeared, leaving just a few internet fan pages and collectors to tell the tale that "Everything would be OK."

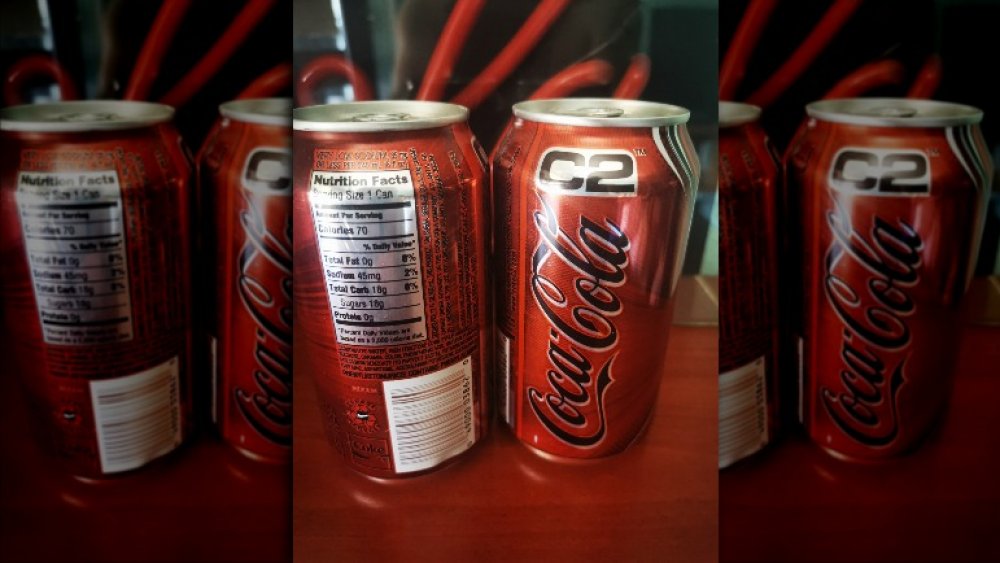

Coca-Cola C2

Coca-Cola C2 was a product destined to fail. According to Harvard Business Review, its sole purpose was to appeal to men ages 20 to 40 who might want to drink diet soda, but wouldn't do it for the fear that drinking diet soda would be perceived as "feminine." Sigh.

So, Coca-Cola put C2 on the shelves in 2004. This drink was like a hybrid diet drink, non-diet drink, with a flavor more-or-less like a normal Coke. It featured half the calories and half the carbs of a regular Coke, and was pushed hard, with a $50 million advertising campaign. A campaign that many simply don't remember because it was a massive failure. Men weren't interested in making the purchase — it just wasn't different enough or appealing enough to opt-in — and women who wanted a low-calorie drink could already opt for zero-calorie Diet Coke.

C2 was quickly pulled from shelves after it became clear that it didn't help grow market share. But true to their mission, Coke applied the mistakes made from the release of C2 and tried again a year later with Coke Zero — it offered a similar taste with zero calories, and it can still be found on shelves today.

Diet Coke Plus Green Tea

Over the years Coke has released a number of different drinks with the "Plus" signifier, often pointing to health-focused additives. Which, to be honest, seems like a pretty obvious strategy to dupe people into thinking they're receiving some sort of health benefit when what they're really just doing is drinking more soda. And anyone drinking soda and imagining it's rife with health benefits is either sadly misinformed or purposely delusional. Either way, sometimes these marketing ploys work, sometimes they don't, and sometimes they work in specific markets while failing in others.

That's exactly what happened with Diet Coke Plus Green Tea which was released in Japan in 2009, according to NBC News. Right at the peak of the green tea health craze, with practically all beverage companies looking for ways to include "antioxidant-rich!" and "includes catechins!" on their branding, there was Coca-Cola Plus Green Tea, trying to play along. Unfortunately according to Watch Mojo, they made a misstep in the taste department and the soda was largely rejected, never making a debut in the United States.

Coca-Cola Vio

There is little that sounds quite as disgusting as fruit-flavored, carbonated milk, amiright? But somehow this idea was given the thumbs up by Coca-Cola execs in 2009 and was released in a limited market under the brand name Vio. According to CB Insights, the drink failed rapidly in the U.S. (was anyone actually surprised?), although apparently it's been given a second-life (although, presumably an also limited life) in India.

Just think for a second about how bad this idea really was. Yes, milk beverages like chocolate milk or strawberry milk are popular with kids around the world, but who in their right mind wants to drink a carbonated "fresh citrus" milk drink? And it's not like marketing directors were helping explain the phenomena very well. According to an article on Time, a Coke copywriter described the drink as "like a birthday party for a polar bear." Uhhhh... what? Obviously, Vio fizzled out fast.

Flavored Cokes

Over the years there have been a slew of flavored cokes introduced to the market. Sometimes they last a year or two. Sometimes they last longer. Many are pulled from the shelves almost immediately. With the exception of products like Cherry Coke, which has a long-lasting fan base and popularity, flavored Cokes tend to go by the wayside after an initial interest by consumers. The Guardian lists a slew of examples, including Diet Coke with Lemon, Diet Coke Vanilla, Coca-Cola with Lime, Diet Raspberry Coke, Coca-Cola Black Cherry Vanilla, Coca-Cola with Orange, and Vanilla Coke. But really, that list just scratches the surface. In 2019 Coke released Coca-Cola Cinnamon, which sounds especially terrible. And they also produced a range of new Diet Cokes with flavors like Zesty Blood Orange and Ginger Lime, all designed to appeal to the Millennial audience. While not every flavored Coke product has failed, it's really just a matter of time before you see them disappear from shelves. Coke is quick to try new things, but they're also quick to kill the products that stop working.

Coca-Cola Life

As with Coca-Cola's short-lived C2 product, Coca-Cola Life has faced similar problems with reception and brand differentiation. The problem is that Coca-Cola Life is another lower-calorie (but not calorie-free) product sweetened with natural sweeteners like cane sugar and stevia. The idea — along with its bright green branding — is to position the soda as a "healthier" option than full-calorie sodas (like Coca-Cola) and artificially sweetened diet sodas (like Diet Coke). According to Beverage Daily, the product has 45-percent fewer calories than the full-calorie soda and Food Navigator points out that in blind taste tests, the product often performs better than other low-calorie or no-calorie sodas.

Unfortunately, low-calorie options like Coca-Cola Life appear to simply dilute the market of buyers interested in lower-calorie or no-calorie sodas, rather than bringing new customers to the market — in essence, people who buy Coca-Cola Life are the same people who buy products like Diet Coke or Coke Zero — they're not new customers. As such, Coca-Cola Life was pulled from shelves in the UK in 2017 and was phased out of its original markets — Argentina and Chile — in the same year. While it can still be found in the United States, Food Navigator points out that it hasn't been performing well. It may just be a matter of time before it gets the ax there, too.

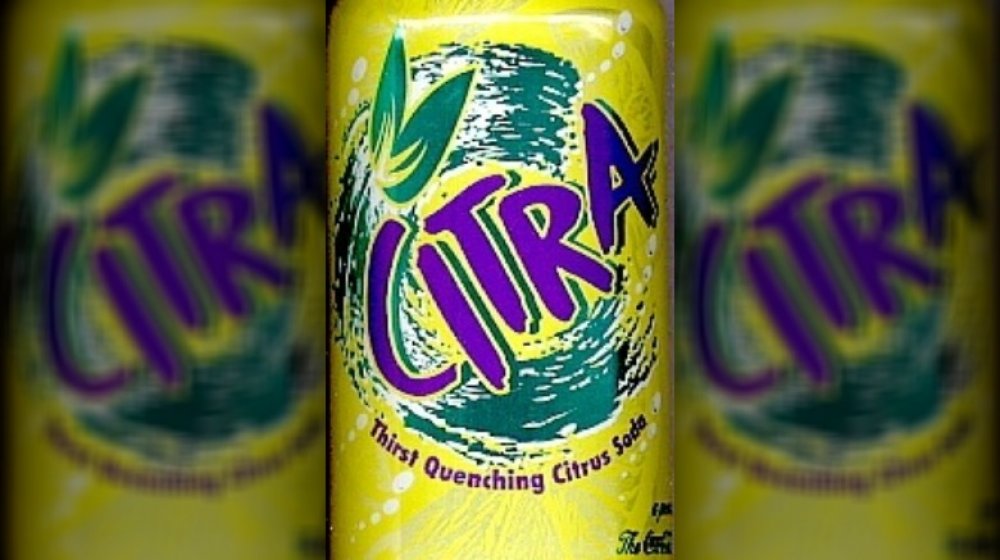

Citra

According to Business Insider, Citra was a grapefruit-flavored, caffeine-free soft drink introduced by Coca-Cola in 1996 as competition for similar-tasting drinks like Squirt and Fresca. While the taste was refreshing and largely well-received by those interested in such a drink, overall sales were lagging and the brand couldn't justify keeping the soda under the Coca-Cola name. Luckily for Citra, Coca-Cola has more than one brand name for different types of drinks, and Citra was phased over to the Fanta brand as Fanta Citrus in 2004 where it still remains.

Keep in mind that the citrus flavor of Coca-Cola products has long been tried and tested under different names and in different markets. As such, grapefruit-flavored Citra is not to be confused with citrus-flavored Surge, or a different Coca-Cola brand, Citra (confused yet?), which is a lemon-lime soda that according to Gurgl was popular in India in the 1980s before Coke ditched it in order to market similar-tasting Sprite. All-in-all, citrus-flavored sodas don't seem to catch on under Coca-Cola branding, so it's probably time for Coke to rethink continuing to try this flavor.