The Truth About Oysters

Oysters. Love 'em or hate 'em (or maybe you haven't worked up the nerve to try them), they seem to be everywhere, with eager oysterites packing bars and restaurants (dollar oysters, anyone?) to get their hands on these curiously stony, sex-changing little creatures from the murky depths. Yes, folks line up in droves to eat these little suckers while they are raw and still alive. These bivalve mollusks (cousins to clams, scallops, and mussels) have played quite a role in world history, with oysters valued throughout the centuries as building materials, fertility aids, treasures, aphrodisiacs, economy builders, saviors of the environment, and, of course, food. But what's the real deal? Do oysters deserve their lofty status? Let's explore the truth about oysters.

Who first ate oysters?

"He was a bold man who first ate an oyster." So said Jonathan Swift, Irish writer and satirist of Gulliver's Travels fame. But Swift probably didn't realize how long early humans had enjoyed the pesky bivalves. Consumption and use of oysters dates to ancient times, with evidence that South African cave men gathered and enjoyed the briny treats as long as 164,000 years ago. Examination of some prehistoric Australian middens (a town's kitchen garbage dump) contain high numbers of oyster shells from as much as ten thousand years old, suggesting the nutritional value oysters held in those burgeoning societies as well.

It was 97 B.C. when the Ancient Romans first gave oyster farming, or aquaculture, a go. A Roman magistrate named Orata decided he was so gaga for the mollusks that he wanted to grow them himself, declaring his rope-grown harvest the finest oysters in all of Rome. His glory didn't last long—Romans soon turned their affections to oysters imported from Ancient Britain. Oyster cultivation, however, stormed the globe, with the ancient cultures of Japan, Greece, and China all lending a hand in creating the oyster farming practices still used today.

Oysters and the city

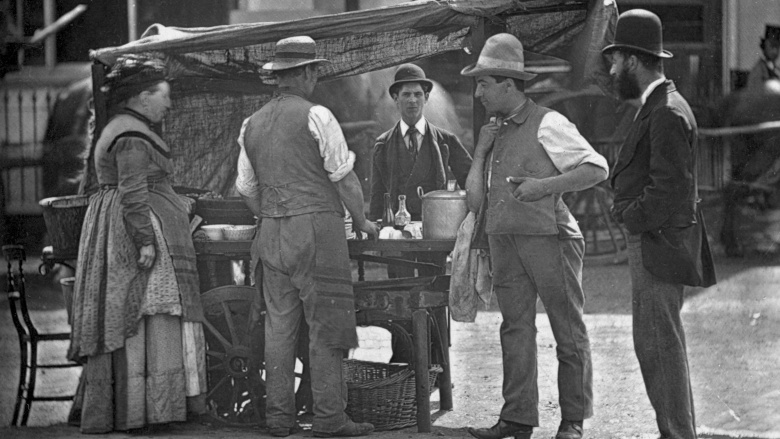

From the 1600s to the early 1900s, New York City was the undisputed oyster capital of the world. The city's lower Hudson River was once populated with 350 square miles of bountiful oyster reefs, estimated to have held more than 50 percent of the world's oysters. The globally renowned oysters brimming forth from these Manhattan beds were fabled to be so succulent and large that writer William Thackeray famously remarked that eating them "was like eating a baby." The affordable briny mollusks were beloved by pauper and well-heeled alike, and available almost everywhere—street vendors, barges, ladies clubs, oyster cellars, and even upscale restaurants, with the tony Delmonico's credited with being the first to serve oysters raw on the half shell.

Oysters meant far more to the residents of New Amsterdam than just a tasty meal. Oyster shells, when crushed and burned for lime paste, became such an important building resource that many homes burned the shells in their own cellars to keep handy for additions and home repairs. The financial district's aptly titled Pearl Street was named for the oyster middens left there by the native Lenape people who once populated New York. It was eventually literally paved with oyster shells.

In 1927, the last New York oyster reef was officially closed. Over-harvesting, rampant pollution, and the destruction of oyster beds due to landfill all contributed to the complete destruction of this once mighty oyster empire. The oysters living in New York's harbor remain toxic to this day. Mark Kurlansky, author of The Big Oyster, quipped, "The history of New York oysters is a history of New York itself—its wealth, its strength, its excitement, its greed, its thoughtlessness, its destructiveness, its blindness and—as any New Yorker will tell you—its filth."

Are oysters really an aphrodisiac?

Of all foods said to arouse X-rated tendencies, perhaps none have obtained such lusty status as the humble oyster. From early days, humans have revered oysters as fertility and libido aids due to their undeniable resemblance to certain parts of the female anatomy. In fact, oysters enjoy such a renowned history of spurring romantic enticement that it is rumored that the famed Venetian lover Casanova himself would down them by the dozen to further cement his storied virility in the bedroom. But are the claims true? Are oysters truly an aphrodisiac?

Well, don't toss out that Viagra just yet. The science remains flaccid on this topic, with the FDA maintaining their totally mood-killing stance that there are no foods that contain aphrodisiac properties. That didn't stop American and Italian scientific teams, however, from determining that some mollusks do indeed contain high levels of amino acids which are said to increase libido. "Yes, I do think these mollusks are aphrodisiacs," said researcher George Fisher of Barry University. We'll have what he's having.

Are oysters good for you?

Oysters boast a wide array of nutrients in each serving, including a high concentration of the essential mineral zinc. This may be another clue as to why oysters are thought of as an aphrodisiac. Zinc deficiency in men can lead to erectile dysfunction and can even cause impotence, while the deficiency in women can interrupt the menstrual cycle and impair the body's production of viable eggs. Add high levels of vitamin D, calcium, B12, copper, iron, potassium, and those Omega 3 fatty acids that your brain and heart adore, and you've got quite a nutritional powerhouse wrapped up in one stony little bivalve. Another bonus? Oysters are super-high in protein but super-low in both fat and calories, making them a favorite of dieters and gourmands alike.

Oysters and the environment

Oysters are pretty incredible little creatures, and they have amazing effects on the environment in which they grow. Oysters are filter feeders, meaning they pull food in from the water around them, filter out nitrogen and pollutants, and vastly improve the water's quality. One mature oyster can filter up to 50 gallons of water per day, so some oysters are used to help clean up polluted waterways all around the U.S. Oyster reefs also provide erosion protection to shorelines, as well as habitats for many fish and shellfish species.

The aquaculture industry (particularly salmon and shrimp farms) has come under fire for its negative impact on the environment, but not so for oyster farming. Oysters do not produce the same waste products as other popular farmed seafood, meaning oyster farming is a sustainable and environmentally sound business. Rowan Jacobsen, author of A Geography of Oysters: The Connoisseur's Guide to Oyster Eating in North America, says, "Oysters are not mere avatars of their environment, either. They help create it. Scientists refer to oysters as ecosystem engineers because they are the key to maintaining estuaries with stable bottomland, clear water, and a flourishing web of life. Supporting sustainable oyster production helps ensure the continuation of that community."

Do oysters really make pearls?

Yes, oysters do make pearls, but not the same oysters that you eat. (This is good news for anyone worried about accidentally sucking down a pearl with an oyster shooter.) Belonging to a completely different biological family of mollusks, it is the Pteriidae family that gives us those prized ocean baubles. Also known as feather oysters due to their fluffy appearance, pearl oysters' creation of pearls is actually a defense mechanism. When a foreign object enters the inner sanctum of its shell, the oyster responds by releasing a liquid called nacre which coats the uninvited invader repeatedly over years, resulting in a natural pearl. The process is the same for cultured pearls: a pearl farmer simply (and delicately!) inserts a small object into a pearl oyster's shell and then waits two or three years while the annoyed oyster works.

Varieties of oysters

American oyster lovers have access to over 100 varieties of the briny bivalves, but you may be surprised to know that they all hail from just five species of oyster. That's right, every oyster you have so far enjoyed stateside has likely been either a Pacific, Eastern (or Atlantic), Kumamoto, Olympia, or European flat oyster. Oysters, however, much to the joy of oyster connoisseurs, take on flavor and texture nuances from the waters they grow in and the ways they have been cultivated (this is sometimes referred to as "meroir"), resulting in distinct varieties often named for their water of origin.

Pacific oysters—like Fanny Bay's—are the most popular type of farmed oyster. They were originally brought to the U.S. from the Asian Pacific and are also referred to as Japanese oysters. Another Japanese import, the Kumamoto, is so widely popular that it's usually just called by its species name, though a good oyster bar will still let you know its water of origin. Kumos grow slowly.

One of only two of the oyster species indigenous to North America, the Atlantic oyster may be the most popular on restaurant menus, and includes the Wellfleet, Malpeque, and Blue Point varieties. The Atlantic oyster's American cousin, the Olympia oyster, was long thought to be extinct, but a stock discovered in the Pacific Northwest has successfully revived the species.

Finally, European Flat oysters, sometimes called Belons (though that name should technically only be used for oysters from Brittany, France) are an oyster lover's dream. They're also the most difficult to come by.

How to eat raw oysters

So you wanna try raw oysters, eh? If you are a first-timer, we recommend you start at an establishment specializing in raw seafood. If you see a sign that says "raw bar" or if "oyster" is in the title of the restaurant, you are on the right track. Seat yourself directly at the bar, so you can have a discussion with your server or the resident shucker. Ask about the varieties available that day. Oysters are often sold per piece, so go ahead and ask for a sampling of the day's offerings. Two each of five or six different varieties of oyster will give you a great opportunity to really assess what you are tasting and what you prefer. You will likely hear descriptive words thrown around that may remind you of a wine tasting—words like "body," "sweetness," "salinity," "aroma," "clean," "creamy," or "smoky." These describe flavor nuances that are directly related to the oyster's species and water of origin, or meroir.

Your oysters will likely be served on a bed of ice, along with some accompaniments like mignonette sauce, cocktail sauce, horseradish, and lemon. Use these toppings sparingly or you risk disguising the oyster's true flavor entirely. When you are ready to dig in, you can rely on the six S's of oyster tasting to guide you, as recommended by the oyster experts from On the Half Shell. See: study the oyster. Smell: the oyster should smell like the ocean, but not fishy. Sip: the oyster should have plenty of juice, or liquor, with varying degrees of salinity. Slurp: tip the oyster meat into your mouth like a spoon. Savor: don't just swallow the oyster whole; chew it a few times to really appreciate the flavors. Shell: flip the shell over and return it to the platter.

How to shuck raw oysters

Hey beginners, put that knife down! It is notoriously difficult, as well as downright dangerous, to shuck an oyster. A far more advisable way to enjoy oysters at home (unless you are a real pro!) is to steam, bake, or barbecue oysters inside their shell. They'll open on their own when they are properly cooked. If any oysters do not willingly open up alongside their mates, many recipes recommend tossing them. Stinky oysters or opened oysters that don't close when you try to push them shut should definitely be thrown.

If you're really determined to learn the proper technique for shucking oysters, we recommend you enlist the instruction of a professional who can guide you in the use of proper equipment such as special gloves, pliers, and an oyster knife. This special knife, with two well-sharpened sides, is used to cut the oyster's strong adductor muscle which holds its shell together, and then pry apart the shells, all the while carefully avoiding slicing your hand or the oyster.

Should you only eat oysters in months with an 'R'?

This idea has been around since 1599, when it first appeared in a British cookbook. Simple enough advice, advising folks to shun consuming oysters in the warmer months of May through August. Lack of refrigeration probably made this a good idea, coupled with the fact that wild oysters spawn in the summer, which has an unpleasant effect on the flavor and texture of their meat.

Avoiding the harvesting of oysters in the summer months also allowed for oyster reefs to replenish. In modern times, however, this old adage doesn't really matter. We have refrigeration and the aquaculture industry staggers the oysters' spawning cycles so they can keep selling all summer long. While wild oysters collected in warm months do still carry a higher risk of foodborne bacteria, commercial oyster fisheries have safeguards to make sure you get good shellfish.

Oyster recipes

Sure, oysters may be typically associated with their raw consumption, but that's just a drop in the ocean compared to the infinite ways they can be prepared. Literature and history are flush with a cornucopia of references to the oyster's culinary usefulness, from oyster stew to oyster pie to oyster fricassee, not to mention the renowned oysters Rockefeller, created in New Orleans in 1899 and named so for its rich flavor and spinach-tinged hue of wealth.

Oyster stuffing, synonymous with Thanksgiving in many American households, is also a time-honored oyster dish. Cookbooks dating as far back as 1685 contain recipes for the mixture of bread and mollusk meat, due perhaps to the chance that people of all classes likely had access to these cheap and plentiful ingredients. It seems they were itching for creative ways to use them.

If you are put off by the idea of this shellfish-filled, savory stuffing, don't be. The flavor is an umami-twinged delight and can be easily made with canned oysters and their juices, called liquor. There is no definitive recipe for an oyster stuffing, so try adding them to your own favorite stuffing recipe or tackle this one from Saveur, made in the New England style.

Shellfish allergies

A love for oysters, both raw and cooked, is not without its share of risk. A shellfish allergy (not the same as a fish allergy) is one of the harshest of food allergies and can develop later in adulthood. Symptoms can seem to come out of nowhere and may include vomiting, hives, wheezing, swelling of the tongue, and diarrhea. The most severe cases can include anaphylaxis, a tightening of the throat that can cause death if not treated immediately.

Most shellfish allergies are related to the crustacean family (lobster, shrimp, crab), but anyone with a known shellfish allergy should check with their allergist to see if mollusks are safe to eat. An allergy specific to mollusks, while not as common, is possible. A small percent of the population has an allergy to tropomyosin, a muscle protein found in mollusks like oysters, abalone, mussels, scallops, and squid.

Oysters and bacteria

Not sweating an allergy? Well, hold on right there before you start slurping willy nilly on those dollar oysters you nabbed at happy hour. Oysters can also contain a very rare but nasty virulent bacteria called Vibrio vulnificus. V. vulnificus, while extremely uncommon, is still the number one cause of death related to consumption of seafood in the U.S., with the highest incidences occurring in oysters found in Gulf Coast waters during the warmer months. Sometimes referred to as a "flesh-eating bacteria," the infection, called vibriosis, is deadly and can cause immediate symptoms including abdominal pain, diarrhea, and vomiting.

Vibriosis is particularly dangerous to those with compromised immune systems, but anyone who suspects they have come in contact with the bacteria should seek emergency care immediately, as it can kill quickly if left untreated. Though cases of vibriosis have so far been few and far between, some believe climate change will increase the presence of the bacteria, which flourishes in warmer waters and is lethal in an estimated 50 percent of foodborne cases.

Your best bet to avoid the dangerous bacteria is to avoid eating any raw seafood. Barring that, buy your raw shellfish from reputable fishmongers and restaurants, who are more likely to sell oysters that have undergone a depuration process that cleanses the oyster of harmful pathogens. Lastly, be mindful when consuming seafood from the Gulf Coast, particularly in summer months.