Value Menu Myths You Probably Fell For

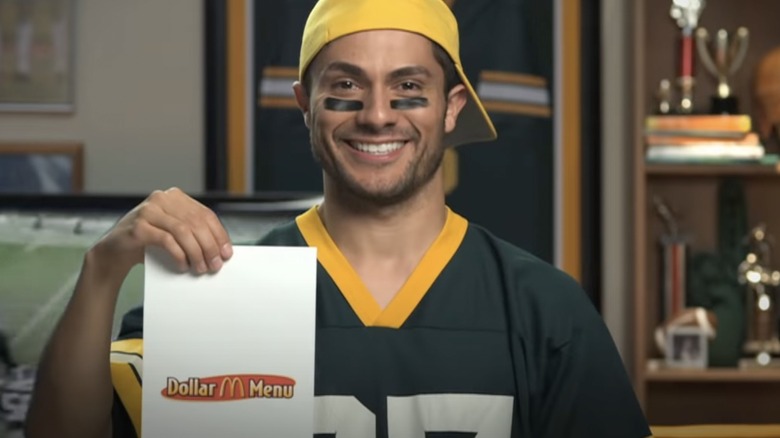

There are few things more undeniably alluring — and ultimately irresistible — than a favorite fast food restaurant's "value menu," or, colloquially, the famous McDonald's "Dollar Menu." For a nice, round price like $1 (or often, $2, $3, or a set bundle of a few items for $4), consumers can get a quick, filling, and varied meal of small and modest fast food favorites of their choosing, creating a combo of their own design that's far cheaper than the $6 or $7 numbered meals also available on the drive-thru board.

The psychology of the value menu at places like McDonald's, Wendy's, and Taco Bell is such that most people assume it's a great deal — those prices are so low that the big fast food companies must be taking a loss on each item sold in such a fashion, or at least enjoying razor-thin profit margins. As it turns out, those value menus are very carefully calibrated to be just as or almost as profitable as anything else on offer, leaving the customer just ever so slightly fleeced or misinformed. Here's every assumed or perpetuated "truth" about fast food restaurant value menus — and a thorough debunking of each.

You can deftly order toppings to customize value menu sandwiches for less money

Social media and the internet in general are lousy with fast food "hacks" — crafty ways to subtly manipulate an order to get more food, more interesting food, cheaper food, or sometimes, it would seem, all three. For many, the idea that they've saved a bit of money getting a big meal for little cost through some savvy, value menu-oriented ordering is almost as satisfying as the fast food meal itself.

But consider the fact that fast food restaurant chains are massive organizations with large corporate staffs who price menu items (and add-ons) as precisely as possible. A lot of research goes into why each thing costs as much as it does, and these sophisticated operations know about most of the supposedly cost-saving tricks before the customers do. The result: The house always wins, and the diner saves very little money, if any. For example, according to Eat This, Not That!, ordering an eggless breakfast sandwich at McDonald's, like a value menu-priced Sausage McMuffin, and then asking for eggs and cheese separately, results in negligible savings. In New York at one point, a Sausage McMuffin with egg cost $3.89. A Sausage McMuffin without eggs went for $1.89, and scrambled eggs cost $1.99, resulting in a total of $3.88, or a savings of a measly penny.

It's cheaper to eat off the value menu than it is to cook something at home

Meat on bread with a side of potatoes, and a soft drink to boot, can cost a customer as little as $3 if they order off of a fast food's value menu or board of $1 bargain items. That's a pretty rock-bottom price for a meal, and one that seemingly can't be beat, especially for one that's already prepared, cooked, packaged, and ready to go.

However, that ultra-low-cost can be deceptive, especially if added up over time, like if customers make a regular habit of eating off the value menu multiple times a day or week. Even with very low prices, it's still cheaper to cook meals in one's home kitchen. For example, Washington Post writer Sally Sampson re-created many fast food favorites at home, and even using pricier, higher-quality ingredients, it cost less money than it would at the drive-thru window. And sure, it might seem expensive to buy things like bread, buns, and meat in bulk, or at least in multiple serving sizes, but without paying for the labor and marketing costs embedded in the price of fast food, those savings ultimately work out to smaller per-meal prices.

The value menu is popular only with people without a lot of money

It's an indelicate or even elitist way to put it, but conventional wisdom holds that fast food value menus are the provenance of the lower-middle-class or low-income demographics. After all, at first glance, convenience foods seem very cheap, or at least less expensive than nicer, sit-down restaurants or the deli offerings at high-end grocery stores that cater to the well-to-do, like Whole Foods. In 2011, Mark Bittman of The New York Times quantified the phenomenon, confidently theorizing that "junk food is cheaper when measured by the calorie, and that this makes fast food essential for the poor because they need cheap calories." For example, if an organic apple cost a dollar, and so did a taco, it would be a better per-calorie value to go for the 140-calorie taco over the 60-calorie apple.

But certain things cross economic divisions, such as deliciousness and bargain-hunting. Fast food, and by extension, value menus, are popular among many segments of the population. In 2013, a Gallup survey found that "Wealthier Americans," or those with at least a $75,000 annual income, were more likely to eat fast food once a week than lower-income residents. A 2018 study from the CDC yielded similar results, finding that more people above the poverty line regularly ate fast food more than those living below it.

"Buy one, get one free" is always a really good and straightforward deal

Some of the bigger national fast food franchises will run a limited-time promotion that expands the perceived savings of its value menu to some of its larger, more alluring, and higher priced items. Either via a couponing campaign or a big marketing campaign, a burger joint might offer a buy-one-get-one-free-deal, in which customers pay full menu price for a large hamburger or chicken sandwich and get a second entree — either the same one, or one of a similar price — for free. That would, in fact, be a deal if the restaurant is above board and on the level and actually holds up their end of the promise — say a double cheeseburger normally costs $4, and so the consumer pays that $4 for two sandwiches. But sometimes, in advance of a buy-one-get-one-free deal, chains will temporarily raise the price of the featured item, thus offsetting any losses they might otherwise suffer during the promotion. To use the earlier example, the restaurant may hike up the price of the double cheeseburger to $5, and if they're selling two for the price of one, they're still making money with each customer's purchase.

According to Nation's Restaurant News, in 2018, Burger King settled a class-action lawsuit, after plaintiffs sued, showing that customers had paid more for two Croissan'wich breakfast sandwiches between 2015 and 2017 with a BOGO coupon than they would have for a single item.

The value menu is a relatively new phenomenon

McDonald's found major success with its Dollar Menu, as did Taco Bell, following with its Dollar Cravings menu. Those came out in 2002 and 2014 respectively, an aggressive push by major fast food companies to cut prices and lure in hungry customers at the height of economic downturns that left many people trying to stretch their food budget. Be that as it may, the idea of a separate menu of specially prized specially sized fast food treats from which a customer could assemble a complete and well-rounded meal for just a couple of bucks is a decades-old concept.

In 1989, according to QSRweb, Wendy's introduced the Super Value Menu, the first of its kind. In response to a fast food war that saw McDonald's and Burger King slash the price of its Big Mac and Whopper, respectively, to a mere 99 cents, Wendy's countered with a selection of seven items with an initial 99-cent price point, including a Junior Bacon Cheeseburger, baked potato, chili, Biggie Fries, and a Frosty. In 1990, per The New York Times, Taco Bell introduced a three-tiered value menu, offering familiar and popular menu items like tacos, burritos, and nachos for 59 cents, 79 cents, and 99 cents.