The Truth About Cured Meat

Some things are just universal truths, and one of those things is the deliciousness of cured meats. Countries all over the world have their own types of cured meats, their own favorite seasonings and preparation methods, their own ways of eating it. Being a foodie might be trendy in today's world, but cured meats? They bring everyone together in a way that no other Instagram trend can.

But how much do you really know about what you're eating? You've undoubtedly heard the rumors — the terrible, horrible, rumors — that cured meats are one of the worst things you can possibly eat, and how true is that? We've managed to make meatless meat, surely, we can make cured meat healthy... right? Are there good options out there? (And by "good," we mean healthy, because let's face it, they all taste good.)

Let's talk cured meats, so the next time you pick up some for your on-the-couch, in-front-of-Netflix charcuterie plate, you'll at least know what you're snacking on.

What, exactly, does cured meat mean?

So here's a question: Do you know what cured meats actually are? According to The National Center for Home Food Preservation, curing meat means that a salt-based concoction (along with sugar and nitrites/nitrates) has been used to preserve not just the meat itself, but also the color and flavor of the piece.

Sounds pretty straightforward, right? There's some debate over those nitrites — and we'll talk more about those — as some don't consider it curing without them. Processes that just use salt are sometimes called salt curing, and the end result is pretty much the same. There's two major different types of curing: one is a wet process, and the other is a dry. The wet is sometimes called brining or pickle curing (when there's sugar involved), and it's done by submerging the meat into a wet brine or injecting the brine right into the meat. Dry curing, on the other hand, just involves the salt mix being rubbed into the meat.

You'll sometimes hear "curing" and "processing" talked about in the same way, so what's the difference? Cured meats are simply one type of processed meats, as "processing" refers to anything that's done to a piece of meat that results in an extended shelf life or change in taste (via the BBC).

What makes cured meat last so long?

We all know that if you take some fresh, raw chicken breasts out of the fridge and set them on the stove only to get distracted by something, you're not going to want to eat them if you only make it back into the kitchen a few hours later. You don't have that worry with cured meats, but why?

According to BBC, it's all down to moisture. When meat is cured it's coated with salt, and that kick-starts a process where all the moisture on the inside is drawn to the skin, where it evaporates. Where there's no water, there's no environment for bacteria to grow and thrive.

In large pieces of meat, there's a bit of a problem: If the salt is just on the outside, the bacteria inside will grow faster than the moisture evaporates. That's why for large hunks of meat, salt solutions are usually injected deep into the center. But it's all a balancing act — if it happens too slow, bacteria grows. If it happens too fast, the surface of the meat goes funky. When it happens just right, though, delicious, bacteria-free cured meat happens, and that's why we've been doing it for so long.

We've been curing meat for a long, long time

Saying we've been curing meat for a long time is no exaggeration — in fact, it doesn't really do the process justice. According to Walden Labs, we've been curing meat since at least 40,000 BC. We know because of cave paintings discovered in Sicily, and we suspect we would have used a combination of salt from evaporated sea water and ash from plants to promote the curing and drying process. That's pretty impressive!

Unfortunately, there's a lot we don't know about our history with cured meats. No one is quite sure when we stumbled across the idea of nitrites, but the Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Service says it was the ancient Romans who first noticed how cured meat changed color to take on a deeper red color once the process was complete. That particular effect happens thanks to the nitrites, so even though we only figured out what they were in the 20th century, we knew something was working some kind of culinary magic centuries before that.

The bacon (and all cured meat) cancer connection

In 2015, the world had a collective meltdown when the World Health Organization announced they'd found processed meats were a group one carcinogen, which basically meant that they had scientific evidence that eating too much of it would increase your risk of developing certain kinds of cancer, especially bowel. They were actually talking about a whole bunch of different kinds of meat, but the world only heard one thing: bacon causes cancer.

That's still pretty abstract, especially when you're sitting there trying to decide whether or not you should make yourself a BLT. But The Guardian put it this way: globally, 34,000 cancer-related deaths each and every year were linked to processed meats. That put things in perspective a bit, didn't it?

The WHO eventually issued a statement telling everyone to stop overreacting, and the meat industry kicked into damage control mode. But in the following years, more scientific studies continued to find links between eating processed and cured meats and higher risks of developing certain types of cancers. And the biggest problem was the very thing that makes us reach for a particular pack of cured meat. It's that pink color, isn't it? That's a sign what you're eating has been treated with something containing nitrites — probably sodium nitrite and/or potassium nitrite — and that's what makes cured meats much more dangerous than non-processed meat.

In case you're not up on your science, you might know potassium nitrate by another name: saltpetre.

What are these nitrites we keep hearing about in cured meats?

Listen to all the hype, and it's easy to believe that nitrates are bad. But it's not that straightforward, says the BBC, and around 80 percent of the nitrates we ingest come not from processed meats but from vegetables. And in those cases, they're a good thing. The nitrates in beets, for example, have been linked to lower blood pressure. They work so well that they're even an active ingredient in some medications, so... what gives, science?

In their normal state, nitrates are pretty harmless. When we eat them, the bacteria in our mouths (and yes, we all have it), converts some of the nitrates to nitrites, and they're a little different. Once they get to the stomach, that's when reactions are kick-started by the acid there, and it's when there's the chance they're going to turn into something carcinogenic. That happens when they're in the presence of another set of compounds called amines. They form nitrosamines, and those nitrosamines also form in foods when they're subjected to cooking at extremely high temperatures, like what happens in that bacon. Bummer.

In other words, it's not the nitrates and nitrites themselves that are harmful, it's all down to the processes they undergo. Unfortunately, it's the processes that happen in processed meats that are bad.

Why are nitrites still used in cured meats if they're so bad for us?

So here's some depressing news. The WHO report in 2015 wasn't new information, and we've known for decades that the nitrates and nitrites present in cured meats are bad for us. In the 1950s, a pair of British researchers discovered that rats regularly fed these substances had a tendency to develop malignant tumors on their livers. Studies through the 1970s supported those findings, and in 1976, a prominent cancer scientist named William Lijinsky argued that even though humans don't have the same biology as animals, we needed to sit up and take notice of the fact that these substances were known carcinogens.

And studies continued. In the mid-1990s, one even linked a regular diet of hot dogs to a higher risk of childhood brain cancer.

But manufacturers are still using them, and according to Farm Journal's Pork, it's justified because of the desirable pink color they produce. There's also the flavor change, the extended shelf life (and less waste), and nitrites' ability to stop bacteria from growing. But The Guardian says there's something else at work here, and it involved profits. Sodium nitrite makes the curing process happen much faster, and the faster they can cure meats, the faster they can sell them. There are other options out there but they're slower, and as food scientist Harold McGee points out, no one's going to want to wait 18 months for a hot dog to cure.

Nitrite-free cured meats are becoming a thing

It's important to note that not all cured meats contain nitrites and in fact, slow-cured and nitrite-free meats are becoming more and more popular.

Take Parma ham. In 1993, all Italian producers of Parma ham dropped nitrites from their processes. Now, they only use salt and age each ham for 18 months, in the same way they did centuries ago. According to The Guardian, some British ham producers have also dropped nitrites, even though yes, the final product does taste a little different without them.

In 2018, The Irish Times reported that a processor in Northern Ireland had finally come up with a way to produce nitrite-free rashers on a commercial scale. The product is called Naked Bacon, and it's flavored with a recipe of Mediterranean spice and fruit extracts instead of the usual nitrites.

Informa Markets says there are a number of producers exploring more and more nitrite-free options, even as food professor Corinna Hawkes from City University in London repeated a warning that the WHO's findings need to be taken more seriously, and that eating cured and processed meats on a regular basis was enough of a risk that governments should step in and decide just how to best warn consumers.

The sodium content in cured meat is sky-high

Not all cured meats are created equal, but one thing they do all have in common is a sky-high sodium content. It's so bad, in fact, that the American Heart Association lists cured meats and cold cuts on their Salty Six chart for both adults and children.

Look at it this way — the AHA recommends limiting your daily sodium intake to no more than 2300 mg, and ideally, you should actually be shooting for 1500 mg. Ham, on average, has 1117 mg of sodium per 3-ounce serving (via Healthline).

Other types are just as bad. A single ounce of beef jerky contains around 620 mg, and 2 ounces of salami has 1016 mg. And hot dogs can be worse still, with sodium amounts varying and hitting numbers as high has 1330 mg. That's almost your entire day's worth of sodium in a single hot dog — without taking into consideration any toppings — and that alone should make you rethink just how many cured meat products you keep in your kitchen.

What makes these different types of cured meats, well, different?

There's a surprising number of different kinds of cured meats out there, and figuring out what you're looking at can be difficult.

Take prosciutto and coppa. They pretty much look like they're the same thing, but while coppa comes from the pig's neck and shoulder, it's only prosciutto if it comes from the leg (via Crush). Then there's other kinds like bologna, liverwurst, and mortadella, and those all kind of look similar, too. But while bologna is an emulsification of beef, pork, or a combination of the two, liverwurst is pork, bacon, and pork liver, while mortadella is pork and neck fat (via Food Republic).

In other words, there's more variables than you might expect when it comes to cured meats. There's air-dried and dry-cured, there's meats from different parts of the pig with different amounts of fat (also pulled from different parts of the pig) and many, many different types of seasonings. But most do have something in common: they're mostly pork. Among them all, there's only a very few that are completely made from beef, including bresaola.

The curious case of the cured hams

So, you know that cured ham lasts for a long time, but just how long are we talking about?

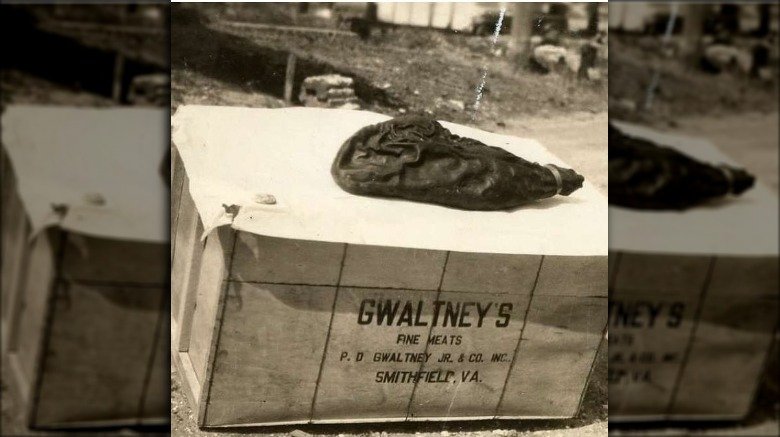

According to the BBC, there's a bit of a debate going on about just what piece of cured ham is the oldest. The contenders include a ham in Smithfield, Virginia's Isle of Wight County Museum, a piece of pig that was originally cured by Gwaltney Foods back in 1902. Atlas Obscura reports that it's still around mostly because it was lost for years, and after it was rediscovered, the lucky finder put a brass collar on it, started calling it his "pet ham," and displayed it around the country as a stunning example of just how time-proof his product was.

But there's another contender, too, a ham said to be cured in 1892 that was purchased at an auction in the mid-1990s and moved to the shop window of an Oxford butcher.

Are they really that old? And are they still edible? Technically, yes, experts say. Cutting off a piece of either and gnawing away at it wouldn't kill you, but it would also be incredibly dry, vaguely rancid, and it absolutely wouldn't taste good. But still, you could say you did it, right?

There's one kind of cured meat that can get insanely expensive

Not all cured meat is created equal, and according to the Guinness Book of World Records, the most expensive type is the Manchado de Jabugo Iberian ham. Yes, it's available commercially, but if you want to get one it'll cost you around $4,620 for a leg. For that, they say, you also get it in a nice presentation box made by a local artisan from wood sourced from the same region in Spain that the pig was raised, and it'd better have a solid gold bow on it, too, for that price.

The BBC says in order to be considered a legitimate example of Iberian jamon, the meat must come from a black Iberian pig raised on fresh pasture and acorns from the oak trees of Jabugo in Andalucia.

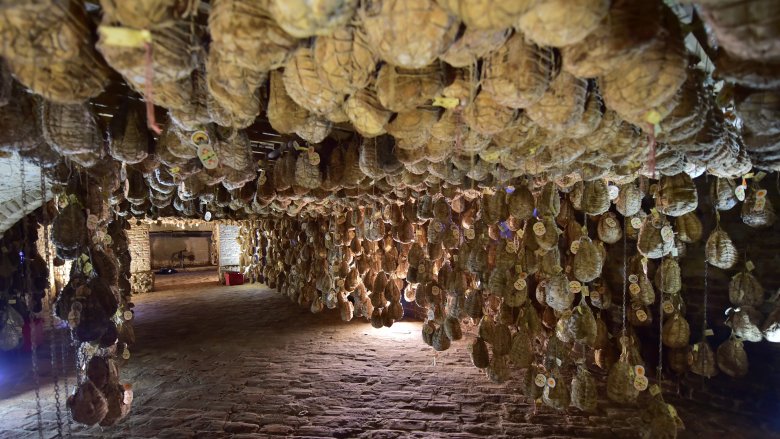

But that super expensive leg of ham is a little different, and comes from the pigs raised, bred, and processed by a company called Dehesa Maladua. They use no growth hormones or antibiotics, and have only been in the biz since Eduardo Donato bought 10 rare, spotted Iberian pigs in 1995. Today, they're raised in a Unesco-protected patch of land notable for the massive trees that produce enough acorns to feed the pigs,which are only slaughtered when they're about 3 years old. Then, the meat is buried in salt for several weeks, hung in an open storehouse for a year and a half, and then cured in a basement for another four or five years.

Some guidelines for how much cured meat you should actually be eating

Cured meats might not be the best for you, but they definitely taste good. And there's some good news: in spite of their warnings, the World Health Organization says (via The Telegraph) that you don't have to give it up completely... just, mostly.

They say that 50 grams of processed meat each day is enough to raise your risk of cancer, and that's about the amount of meat that's in a typical sausage. Think of it more as an occasional treat than a regular meal, and there's nothing wrong with the occasional indulgence.

And there are other, better options out there. Look for nitrite-free version of cured meats, and opting for chicken sausages instead of pork is going to be a healthier choice, too. What about that charcuterie board? Are there options for something that's a little less pepperoni and chorizo, but still tasty? Absolutely! Go heavier on the tangy brined foods like olives and pickles, add some dried and seasonal fruits and vegetables, opt for nuts, pate, and hummus, and as for the meats? There's actually a variety of uncured meats out there. Look at it this way: you want healthy bowels, right? We thought so.