15 Whiskeys Presidents Sipped When They Unwound

Being the president of the United States comes with a lot of pressure. From wars and economic crashes to professional and personal criticism, entering the Oval Office has always meant non-stop responsibilities. So it's no surprise that whiskey has seen its fair share of the White House. At the same time, the story of whiskey in the Oval Office paints a larger picture about the country itself.

As America changed, so did its whiskey. Early presidents like Washington and Madison drank rye whiskey made close to home. As the country expanded west, corn-based bourbon became more common, and presidents like Jackson and Grant favored it. Later, increased global trade and international influence introduced Scotch into social circles, which leaders like Johnson and Eisenhower preferred. And as cities grew and drinking culture evolved, cocktails became more mainstream, and presidents like McKinley and Roosevelt embraced that shift. Each president's choice of whiskey — as well as how they drank it — reflects the country they were leading at the time.

This list isn't just about every president's favorite drink. Instead, it's a time capsule of America's history, told one pour at a time.

George Washington: Mount Vernon rye

During the time of George Washington's presidency, grain spoiled quickly and clean drinking water wasn't always reliable. Due to this, distilled spirits were treated as a necessity. Spirits weren't just a way to unwind for the first president — they were truly ingrained in his lifestyle. For Washington, that spirit was Mount Vernon rye, a locally made rye whiskey made from crops grown on his own land. Throughout his presidency, Mount Vernon rye became a regular presence at the table, including in his famously boozy holiday eggnog.

Whiskey also played an important role in Washington's political agenda. In rural America, distilled spirits functioned as currency because they were easier to trade and transport than grain. When Washington approved a federal tax on distilled spirits in 1791, farmers and distillers pushed back hard. And their resistance escalated into the Whiskey Rebellion.

After leaving office, Washington returned to Mount Vernon and fully leaned into the business of distilling. He built one of the largest whiskey operations in the country, distilling 11,000 gallons of rye whiskey in a single year.

James Madison: Rye whiskey

James Madison took office during a tumultuous time in American history. Trade routes were disrupted, ports were blocked, and imported goods from Europe — including wine and spirits — became harder and more expensive to get. Due to this, Americans leaned heavily on what they could make at home. In the Mid-Atlantic and Upper South, rye whiskey became the primary distilled spirit. And the fourth president drank a lot of it — rumored up to a pint a day.

As indulgent as a daily pint of whiskey might seem, it actually wasn't that uncommon back then. Due to frequent contamination of drinking water, whiskey became a common way to hydrate in the early 1800s. Rye whiskey wasn't the only alcohol Madison enjoyed, though. He also loved a large pour of Champagne as well. However, Champagne during that time period was heavily sweetened, so it often came with a next-day headache — an inconvenience that was easily avoided if he opted for whiskey.

Andrew Jackson: Tennessee bourbon

When Andrew Jackson came into office, Americans were drinking more alcohol than before. Jackson's drink of choice was a corn-based whiskey distilled locally in Tennessee, which would be known today as a Tennessee bourbon. This raises the obvious question: Is bourbon actually any different than whiskey? The short answer is that bourbon is a type of whiskey distilled with at least 51% corn.

Whiskey, whether it was rye-based or corn-based, showed up everywhere — at breakfast tables, in meetings, and even at inauguration parties. The seventh president was a huge supporter of including whiskey in everyday life, and it fit his image as a man of the people. Jackson believed that whiskey was the drink of farmers, soldiers, and laborers — not elitists and aristocrats.

In order to make a point about who the presidency actually belonged to, he invited large crowds into the White House after his 1829 inauguration and served a whiskey punch that never stopped flowing. Thousands of people attended, furniture was destroyed, and guests trashed the place. The crowd got so rowdy that staff had to move the punch bowls outside to lure people out. It remains one of the most chaotic inaugural receptions in U.S. history.

Martin Van Buren: Any whiskey

They called Martin Van Buren Blue Whiskey Van for a reason. Van Buren was a heavy drinker, known for putting away large amounts of whiskey without appearing drunk. Unlike some presidents, whose preference was clearly documented, there's no single brand or bottle tied to the eighth president. However, Van Buren was born and raised in New York and started his political career in the Northeast. During that time period, rye whiskey continued to reign supreme. So if he was drinking what was most common and affordable, it would've been rye whiskey.

Van Buren came into the presidency during a moment of economic crisis, and he faced intense pressure throughout his presidency. At the time, whiskey wasn't just an indulgence — it was a normal part of how people gathered and conversed. Taverns doubled as meeting rooms, and talking business meant doing so over a heavy pour. Through it all, Van Buren was known for his sharp political instincts and calm public demeanor, even after knocking back glass after glass.

James Buchanan: Old Monongahela rye whiskey

For James Buchanan, Old Monongahela rye whiskey wasn't a preference as much as it was what he grew up on. Buchanan was born in Pennsylvania in 1791, so he naturally came of age in a place and time where farmers grew rye near the Monongahela Valley, which was later turned into a bold, spicy whiskey that fueled the hard-working people of America. Known as a working man's whiskey, Old Monongahela rye represented the everyday people Buchanan came from long before he ever became the 15th president.

Buchanan wasn't shy about what he liked, so he had no problem unwinding with a glass of whiskey once he got into the White House. He even bought his preferred drink regularly in large quantities from a Washington merchant named Jacob Baer. It was something he drank regularly, and he kept it on hand to share with the world when hosting others around his table.

Ulysses S. Grant: Old Crow bourbon

Ulysses S. Grant entered the White House in 1869 with the lingering stress of leading Union forces through the Civil War. So it's no wonder that rumors quickly spread about his relationship with alcohol, claiming he drank way too much way too often. But nonetheless, the 18th president did drink, and he was often linked to Old Crow bourbon.

This well-known Kentucky bourbon was closely tied to early bourbon-making in the state, produced in a region where corn-based whiskey and charred oak barrels were abundant. Distillers in Kentucky were refining methods that helped bourbon develop a clearer identity, even before official rules existed to define it. Old Crow emerged from that moment as a name people recognized and trusted.

Old Crow bourbon was a recognizable name in America at the time. It was the kind of whiskey Americans referenced as something familiar and dependable, standing out in the industry for its purity and quality. And in a rapidly industrializing America still recovering from war, that kind of consistency mattered.

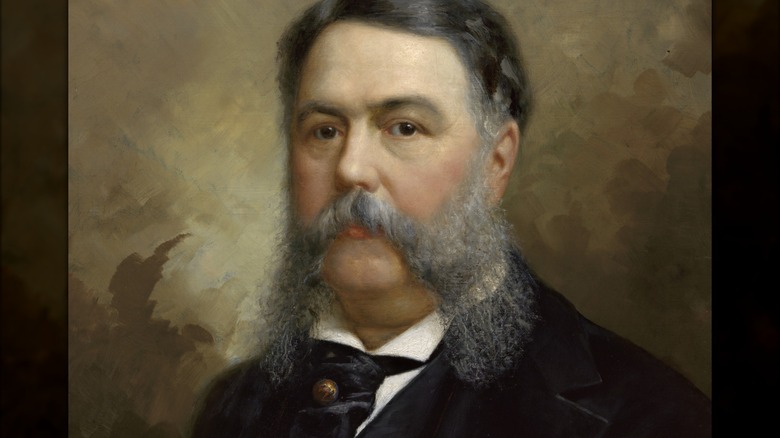

Chester A. Arthur: Whiskey highball

When Chester A. Arthur took office as the 21st president in 1881, he was fond of a whiskey highball. For this tipple, the whiskey was typically mixed with soda or, in later years, ginger ale, making it feel a little more civilized and modern from the earlier days of slinging whiskey straight. Arthur's presidency landed in the middle of the Gilded Age, when whiskey was everywhere but not always trustworthy. Counterfeit spirits were common during this time, so quality varied. Due to this, consumers were starting to rethink what was in their glass.

Arthur became president at a trying time, though. Professionally, President Garfield had just been assassinated. Personally, he was privately grieving the loss of his wife just a year earlier. So a drink to unwind was a necessity. And a whiskey highball diluted the spirit just enough to make a somewhat unpredictable drink feel a bit safer. But dilution, like whiskey itself at the time, was easy to get wrong, and is often one of the biggest mistakes people make when mixing whiskey highballs.

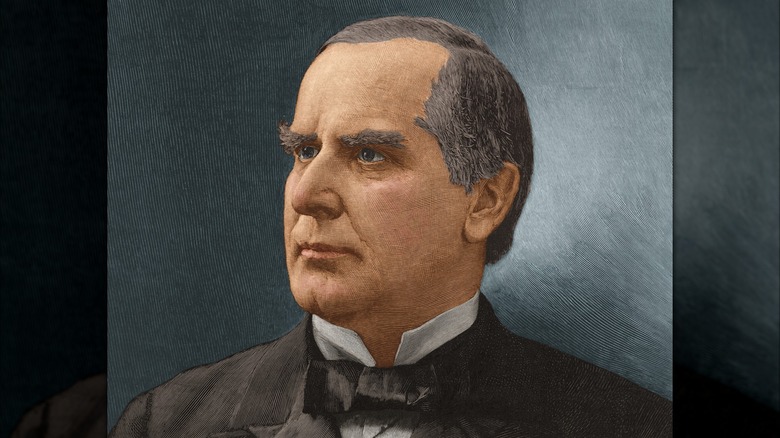

William McKinley: McKinley's Delight

William McKinley didn't just drink whiskey — he had his own whiskey cocktail named after him. A McKinley's Delight is made with rye whiskey, sweet vermouth, cherry brandy, and a touch of absinthe. This drink encompassed how whiskey was being consumed during the time McKinley was president. It was served as refined cocktails in hotel bars and parlors rather than poured straight from a jug.

That shift also mirrored what was happening with production methods, too. Industrialization was changing the distilling process, turning small operations into large-scale producers. Brand names started to matter more. As a result, bottled whiskey became more common, which replaced anonymous barrel sales and gave people a spirit they could actually recognize and trust again.

At the same time, the Spanish–American War was fueling nationalism, and people started viewing American products as things worth celebrating — including spirits. The McKinley presidency marked a growing pride behind American whiskey, and cocktails like McKinley's Delight offered a way to show off that patriotism in a glass.

Theodore Roosevelt: Mint julep

Cocktail culture continued to boom through the 19th century, and it even followed the next president into the White House. Theodore Roosevelt's whiskey cocktail of choice was a mint julep, a mixed drink built on bourbon or less commonly rye whiskey, sugar, mint, and ice. Unlike a smash, which is often confused with a julep, the julep remains intentionally simple and lets the whiskey do the talking. It's meant to be sipping slowly rather than thrown back. And it showed that whiskey had become something more refined in American life.

During Roosevelt's presidency, the food and drink industries were being pushed toward reform and accountability. In 1906, the Pure Food and Drug Act cracked down on fake and adulterated spirits, forcing distillers to be honest about what was actually in each bottle. This completely changed how whiskey was labeled and sold. Whiskey now had rules — and distillers faced real consequences for breaking them. And the mint julep fit neatly into this new era.

Woodrow Wilson: Scotch and soda

Woodrow Wilson was the first president to sit in the White House during Prohibition. Yet oddly enough, he still enjoyed an alcoholic beverage every now and then. In fact, Wilson didn't even support strict alcohol laws, and even tried to stop the main law that enforced Prohibition. Despite the ban, his drink of choice was often a Scotch and soda.

When it comes to ingredients and distilling process, there are some differences between Scotch whisky and bourbon. Whiskey is just the broad category while Scotch and bourbon are specific whiskeys made under different rules and in different locations. The main difference between Scotch and bourbon is that bourbon is an American whiskey made from corn, and Scotch is a type of whiskey made in Scotland from malted barley. By the time Wilson was president, Scotch was seen as a refined and well-known spirit in the U.S.

When Wilson left the White House in 1921, transporting alcohol was illegal. Because of this, he asked Congress for special permission to move his personal supply of wine and a cask of Scotch to his new home in Washington, D.C. This made him one of the few people legally allowed to move alcohol during Prohibition.

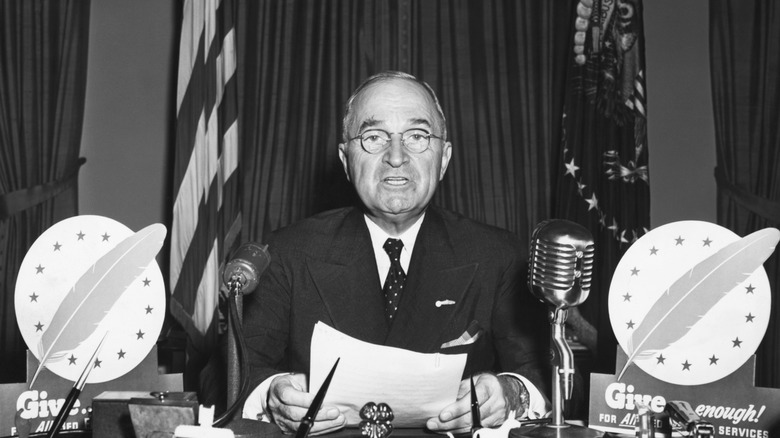

Harry S. Truman: Bourbon Old Fashioned

By the time Harry S. Truman took office in 1945, Prohibition had ended over a decade earlier, and whiskey was back to being heavily enjoyed by the American public — including the 33rd president himself. He reportedly started each day with a shot of bourbon, and was also a big fan of a classic Old Fashioned cocktail. As well as being partial to Old Turkey, his bourbon of choice was Old Grand-Dad — a spicy, high-rye bourbon that was known for its bold flavor.

Post-Prohibition America had its fair share of problems, though. Many distilleries had closed for good during the dry years. Equipment had been sold and repurposed, and skilled workers had moved on to other industries. When legal drinking returned, demand for whiskey surged faster than anyone could recover. Shortages followed, quality varied, and it would take decades for American whiskey to fully rebuild its supply and reputation.

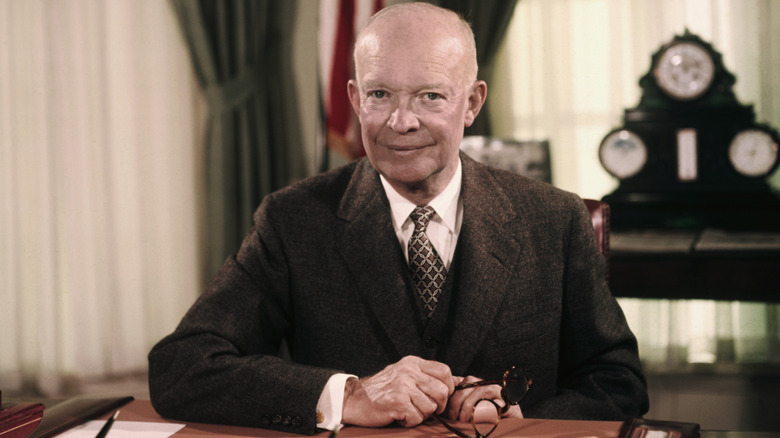

Dwight D. Eisenhower: Chivas Regal Scotch whisky

Dwight D. Eisenhower's presidency happened during a time when cocktail culture was thriving. Old Fashioneds, Manhattans, and Highballs were everywhere, and it was clear that whiskey was back to being confidently consumed in the decades after Prohibition ended. At the same time, the demand for imported Scotch was growing. Many American soldiers drank Scotch overseas, and the taste for it followed them home. So when Eisenhower took office in 1953, his spirit of choice to unwind was Chivas Regal Scotch whisky, served with soda.

Eisenhower wasn't a heavy drinker. After suffering a heart attack while in office, he became more careful with his health. Still, the ritual of enjoying a Scotch (or two) at dinner continued. This preference of Scotch whisky was also a reflection of how American drinking habits were being internationally influenced, and how spirit consumption was expanding beyond domestic whiskey.

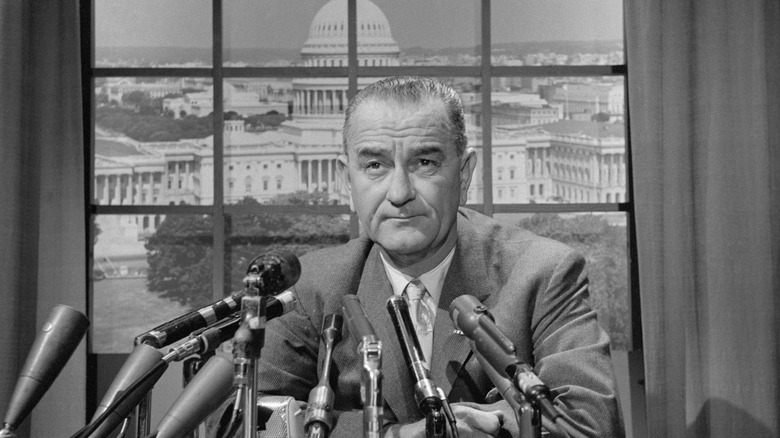

Lyndon B. Johnson: Cutty Sark Scotch

Lyndon B. Johnson's whiskey preference came during a shift in American drinking habits. Vodka was rising fast, marketed as a clean and modern spirit. Because of that, whiskey was losing its spotlight. It hadn't disappeared, though — especially for older generations. Whiskey became a symbol of authority and tradition, so it stayed mainstream in political circles in Washington.

Johnson's choice drink was Cutty Sark Scotch, a spirit that blended the new postwar drinking era with old-school credibility. He enjoyed drinking Cutty Sark as a Scotch and soda, often mixed much lighter than his guests'. It was rumored he did this to stay sharp while meeting with his political opponents. While he wasn't engaging in high-stakes political discussions, he took a more lax approach to drinking his Scotch — often driving around his Texas ranch with a full cup of Scotch in hand, and a secret service agent ready with the bottle to refill.

Ronald Reagan: Maker's Mark Kentucky bourbon

Whiskey was struggling in the 1980s when Ronald Regan entered the White House. Many distilleries closed or merged as demand shrank, and few producers stayed in the game. Maker's Mark was one who stayed, and Reagan himself favored the distillery's Kentucky bourbon. He even asked for a bottle to be put on his pillow on the evening of his 1984 presidential debate with Walter Mondale.

And just as Ronald Reagan loved Maker's Mark, Maker's Mark loved him right back. When Reagan began his presidency in 1981, Maker's Mark went on to release a limited batch of commemorative bottles to mark the occasion. To this day, the distillery proudly leans into its connection with American history, proving that loyalty and patience can outlast any industry trend. While you can enjoy bourbon neat, the spirit's balanced and approachable flavor profile has also made it a staple in some of the best Maker's Mark cocktails.

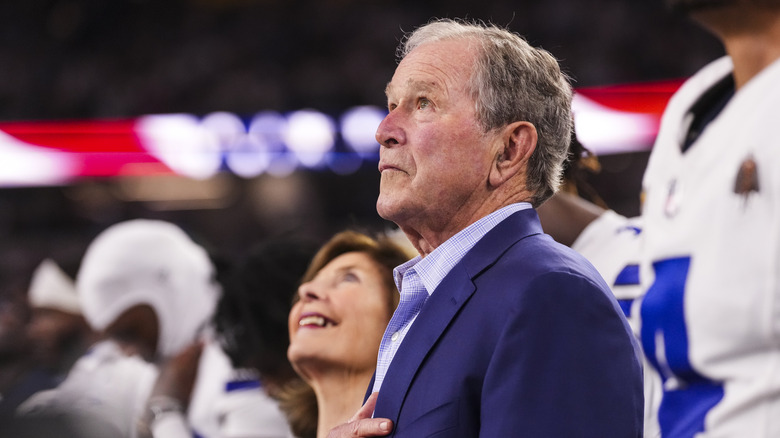

George W. Bush: Jim Beam bourbon

Before becoming president in 2001, George W. Bush enjoyed drinking — maybe a little too much. During his younger years, Jim Beam bourbon was a huge part of his social life. However, that all changed in 1986 when his 40th birthday got a little too wild. Rumors have gone around that Laura Bush gave him an ultimatum about his drinking, but she claims that's untrue. Since then, Bush has sworn off alcohol for good. And he hasn't looked back.

By the time Bush entered the White House, he was fully sober. In a country where drinking had long been commonplace and expected, that lifestyle reflected a growing shift toward sobriety, health, and ultimately just being more conscious about what we're putting into our bodies. For Bush, swearing off alcohol wasn't just a personal choice — it was a decision that introduced a new kind of normal into society.