The One Drink Coke Wishes You Forgot

At first blush, one might assume that New Coke, the brand's best-known gold medalist in the Epic Fail Olympics, would be the drink that leaves Coke so red-faced that it wishes you had selective amnesia. After all, a massive backlash, complete with protests and petitions, drove the company to abandon New Coke after a meager three months – technically 79 days, according to CNBC. But at second blush, you might suspect that this assumption is probably poppycock. Coca-Cola's own website describes New Coke as "one of the most memorable marketing blunders ever," and the company wears the product's implosion like an ironic badge of honor.

Rather than run from flops, the Coca-Cola Company gives out an innovation award for products that fall flat on their faces as a reminder to "celebrate failure." Coke CEO James Quincey even referred to the fear of creative risk-taking as "the New Coke syndrome" during an interview in which he essentially argued that success is a lesson learned from failure.

That probably means Coca-Cola's less-memorable blunders would be praised as necessary hiccups on the path to profits. Even so, the brainchild that Coke seems most likely to want to disown might be sitting right under your nose. It's the opposite of New Coke: old Coke, whose history is littered with ugly and unfortunate associations that the company hasn't exactly celebrated.

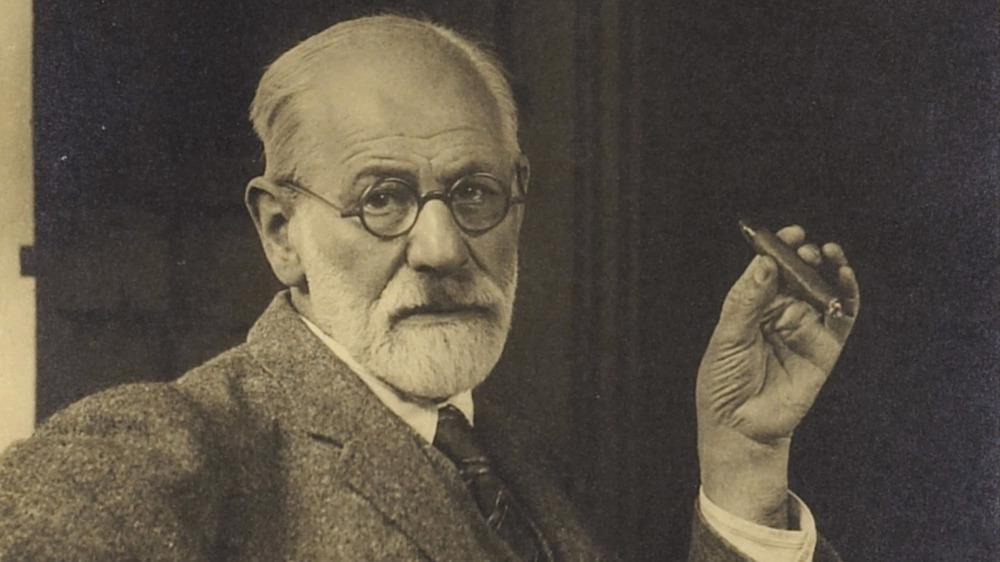

Close but nose cigar

In 1884, future psychoanalyst, cigar enthusiast, and ultimate mama's boy Sigmund Freud published "Uber Coca," an undoubtedly stimulating analysis that sang the praises of cocaine. As recounted by PBS, in 1885, Freud gave a copy of the document to his "dear friend, Coca Koller," the nickname of ophthalmologist Carl Koller. It just so happens that Coca-Cola inventor John Pemberton registered an early version of the drink that same year, per The Daily Meal. The Pharmaceutical Journal interprets "Coca Koller" as a witting (and witty) play on the drink's name, but the American Academy of Ophthalmology sees it differently, calling an intentional connection between the names unlikely.

Even if Freud knew nothing about Pemberton's work with Coca-Cola, Pemberton knew of Freud's work on coke, according to Christopher Cumo's Foods That Changed History. Freud had a high opinion of the drug, which passed his sniff test repeatedly as he got hooked. The Journal of Cutaneous Diseases claims he was responsible for his friend, Ernst von Fleischl-Marxow, becoming "the first cocaine addict." Freud administered the drug to combat his buddy's morphine habit, which stemmed from trying to kill the pain of a major injury.

Notably, Pemberton was afflicted by morphine addiction after being injured in the Civil War. Between Freud's findings and separate reports of Peruvians chewing coca leaves to live longer, he concluded that a cocaine-laced elixir could replace morphine. Hence, the original iterations of Coca-Cola contained about nine milligrams of nose sugar per glass.

Why Coke kicked its coke habit

Billed as an "intellectual beverage" and "brain tonic," Coca-Cola was John Pemberton's second stab at a coca-based drink. New York Times contributor Grace Elizabeth Hale notes that he tried to peddle French Wine Coca in 1884, basing the drink on a French beverage that contained cocaine. A local alcohol prohibition put that ambition on ice, and Pemberton marketed the booze-less Coca-Cola as a "temperance drink." This wasn't just a response to his sober new reality. Banning booze was used as an excuse to arrest black people and other nonwhites and as a pretext to target Catholics.

Coca-Cola had been a drink for white, middle-class consumers. As it became more affordable, whites were consumed by fears that "negro cocaine fiends" with "superhuman strength" were murdering men and preying on women, per the book Illegal Drugs. By 1903, Coca-Cola had kicked its coke habit and added more sugar and caffeine to the soda to compensate. For decades, the old "new" Coke would be marketed specifically to white people.

The Coca-Cola Company has obviously seen the error of its ways since those ugly days, and in what some might see as a quiet mea culpa, it has donated money to the NAACP. In 2020, the company announced it was upping its spending among black-owned suppliers by $500 million to signal its commitment to diversity. But understandably, you shouldn't expect to find many references to cocaine or "memorable" prejudice on its website.