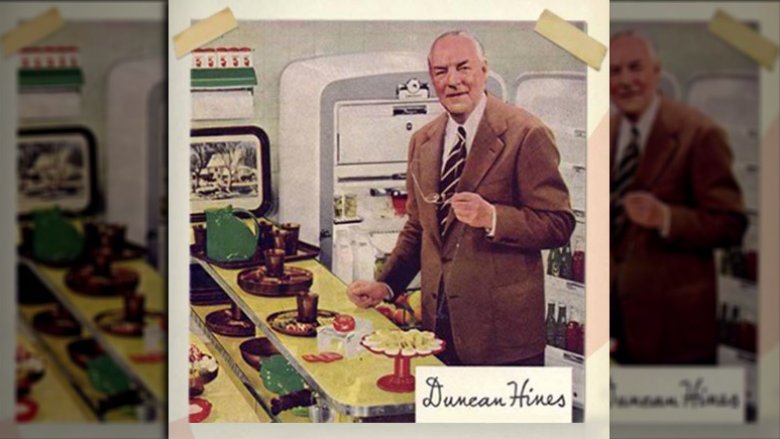

The Untold Truth Of Duncan Hines

Check anyone's kitchen cabinets and you'll probably find a box or two of Duncan Hines cake mix. It's been a staple for birthdays and emergency parties for decades, and if you've ever asked yourself just who Duncan Hines actually was, you're not alone. You might be surprised, too, to learn that not only was he a real person, but that he was perhaps one of the most unlikely people to be immortalized with his own line of baking products.

It didn't start with cake

Today, you know Duncan Hines for his cake mixes, but that's not where it started. Duncan Hines licensed his image to Hines-Park Foods, Inc. in 1949, and their first product was ice cream. Knowing even then that the way to customer's heart is through their sweet tooth, this ice cream contained more butterfat than other commercial ice creams, making it even more tasty. It was more expensive than other ice creams, but it still flew off shelves.

The label used to sell a lot more

Hines-Park Foods, Inc., got even more serious about their brand after the success of their ice cream, and set out to bring high-quality, high-convenience products into American kitchens. There were once more than 250 products that included everything from coffee makers and cooking ranges to pickles and mushrooms. But one thing they still didn't sell in those first couple years? Cake mix.

The cake mix was an instant success

The cake mixes finally came along in 1951, and Duncan Hines (the man) had nothing to do with their creation. Most of the commercial cake mixes at that time contained powdered milk and powdered eggs, and they were as popular as you'd expect. A food chemist named Arlee Andre perfected the Duncan Hines mix that called for fresh eggs, and it was so popular that within weeks of hitting the shelves, they had taken over about half the market for cake mixes.

The found their niche

After finding the secret to a tasty cake mix, the Duncan Hines brand knew they had found their strength — making easy bake goods attainable to all home cooks. They followed up with a pancake mix in 1952, and a mix for blueberry muffins the following year, in 1953. The Duncan Hines brand you know and love was born.

Duncan Hines couldn't cook

Duncan Hines isn't just a line of baking mixing mixes — it was named after a real man — but he's not who you'd expect. Hines not only wasn't a chef, he could hardly cook. During the 1920s, 30s, and 40s, Hines crisscrossed America and took most of his meals at diners and restaurants that were popping up in response to the growing number of families who owned cars and took road trips. Hines himself was a salesman who sold office supplies, and since he was on the road so much, he experienced the questionable food travelers were forced to subsist on firsthand... and he decided to do something about it.

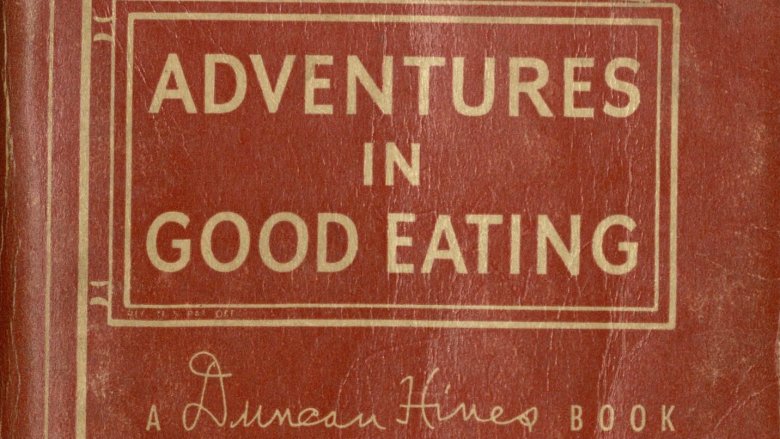

He reviewed a young Colonel Sanders

At the time Hines was traveling, there was no way to tell what you were getting when you stopped for food. Hines decided he was going to change that, and started carrying a journal, making notes on the taste and quality of the food. He turned that into a pamphlet he sent out with Christmas cards. So many people wanted copies that he published Adventures in Good Eating in 1936, and continued releasing annual editions.

Most of the restaurants he reviewed are long gone now, but there's still a handful of them scattered across the country. In 1939, he reviewed one particular place that's evolved into a familiar chain, writing, "A very good place to stop [...]. Sizzling steaks, fried chicken, country ham, hot biscuits." That place was the Sanders Cafe, the restaurant of future KFC mogul Colonel Sanders.

He wasn't the nicest guy to those who knew him best

You might envision someone who has his name on cake mixes being a happy, jolly sort of person. But Louis Hatchett's biography of the food mogul is filled with claims that seem to indicate Hines was anything but, painting a picture of someone who absolutely let the success of his books and his renown as a trustworthy sort go to his head.

According to the biography, Hines hired his secretaries based on who he found attractive. His second wife divorced him, citing "cruelty" as the reason. He also had at least one family member — a nephew — work for him for a short time only to quit because of the abuse he claimed he suffered at Hines's hands.

There's also a suggestion that Hines disliked a vast percentage of the people he was writing for. Hatchett says not only did he rely on and hire people who were already successful because he felt they could be trusted, he felt that unsuccessful people absolutely couldn't be trusted, and during the Great Depression and the war years, that was a heartbreakingly high percentage of the American population.

His favorite cocktail was insanely nasty

The down side to being a food critic is the inevitable weight gain, and Hines took three months off every year to get himself back in shape. While he was home, his wife tasked him with only two kitchen duties: making the coffee and the salad. Hines's off-the-road diet was a healthy one, and there was only one thing he indulged in. That was a particular cocktail that was the creation of wife Clara, and you might only want to give this one a try if you're very, very brave.

The special cocktail called for gin and grenadine, and then the juice of watermelon pickle, some lime juice, orange-blossom honey, cream, and a whole egg. Hines wasn't just fond of them, he was fond of drinking a dozen or so at a time, even though that has to make your favorite odd food concoction look positively mainstream.

He wrote a book of hotel reviews, too

After the success of Adventures in Good Eating, Hines branched out a bit and started publishing Lodging for A Night as well. Described as "A directory of hotels possessing modern comforts, inviting cottages and modern auto courts, also guest houses whose accommodations permit the reception of discriminating guests," the book was designed as a companion to his eating guide, and according to Hines, it was oft-requested.

He took five things into consideration when deciding what kind of review each place would get: cleanliness, quietness, whether or not the staff could be courteous and helpful without being obtrusive, hospitality, and how comfortable the beds were. The guide is still a fascinating read that provides a look not only into the morals of the day, but Hines's morals, too. He took pains to stress that innkeepers should always adhere to a code of ethics that involved things like not allowing drinking, and only accepting guests who brought luggage.

He charged restaurants to use his Seal of Approval

Being included in Hines' travel guide was a huge honor, and since Hines didn't allow people to buy their way in, he needed to make his fortune another way. That was by awarding the Duncan Hines Seal of Approval, which came with some advertising signage restaurants could proudly display. Hines then charged restaurants to use his name and the seal they had (fairly) earned. At a time when most families were averaging about $3,000 a year for their income, Hines was cashing in at around $38,000 a year just for selling the right to display his seal.

He was getting some other sweet deals along with that, too. All the restaurants that were showing off their seal also had to sell his books, and the group of elite restaurants were called the "Duncan Hines family". Since families treat each other to nice things, it's not entirely surprising that the one year, the restaurant owners even got together and bought him a Cadillac convertible for his birthday.

His childhood was colored by tragedy

Duncan Hines became a household name because of his honest opinions and his guides — he never allowed for the sale of advertising in his books, as he said his name hinged on his honest, straightforward opinion — but everyone has to get their start from somewhere. Hines was born in 1880 in Bowling Green, Kentucky, and was one of 10 children. Only six survived past their infancy, and his mother died when he was only 4 years old.

His father found himself unable to care for his remaining family. Hines and one of his brothers were sent to the care of his maternal grandmother, who lived just down the street from the rest of his family.

As typical of the thought processes of the very young, he called her "Grandma Duncan", and it was this grandmother who he would credit with giving him his lifelong love of food. "Food was just something to fill the hollow space under my ribs," he was quoted as saying. "Not until after I came to live with Grandma Duncan did I realize just how wonderful cookery could be."

He once caused a train accident

While Hines's grandmother might have raised him to have a love and respect for good food, that doesn't mean his childhood didn't have some epic anecdotes. Louis Hatchett is Hines's biographer, writing Duncan Hines: How a Traveling Salesman Became the Most Trusted Name in Food, and he tells one story in particular that sounds like it's right out of a Mark Twain novel.

Hines apparently had some sort of fascination with trains, and according to Hatchett, he was known for greasing train tracks as they went up a hill, slowing and stopping them completely. He caused at least one major accident, too, when he built a snowman on the tracks. The engineer of an approaching train not only slammed on the brakes, but did so fast and hard enough that several of the cars were uncoupled. Dangerous? For certain.

He was fanatical about food safety at a time when there was none

When you look at the scope of human history, food safety is a relatively new thing. The FDA wasn't even organized until 1930, and at the time Hines was traveling across the US, health and safety regulations for restaurants weren't something that were frequently monitored.

For Hines, food safety was one of the most important things he looked for in the restaurants he reviewed. He wrote, "The kitchen is the first spot I inspect when in an eating place. More people will die from hit or miss eating than from hit and run driving."

Many of the restaurants Hines visited were well off the beaten path, and their clientele were at the mercy of owners and staff who didn't have the constant threat of health inspectors. Hines looked at everything from how staff and chefs handled their food to what went into the garbage. Cleanliness was key to getting one of his recommendations, and at the time, Hines's opinion shaped the way Americans thought of eating out. He was known as America's Foremost Food Authority, and that's something that no one took lightly.

A man once sent him a blank check

In 1946, Life did a profile on Hines and his work, shining the spotlight on just how important he was not only to the development of the American restaurant industry but to the people who were eating there. They had given him their complete trust, and there was a massive number of them: at the time, around 900,000 copies of his guidebook had been sold. In addition to having 400 volunteer reviewers working with him, he was still traveling 55,000 miles a year for his first-hand look at some of America's restaurants.

People weren't just trusting him to guide their culinary choices, either, and the full extent to which Hines had cultivated an image of being the ultimate trustworthy soul is best illustrated by a blank check he once received in the mail. According to the story, a complete stranger who was living in New England at the time had decided he wanted to buy a 40-acre farm in Hines's native Kentucky. The man sent him a blank — and signed — check, and asked Hines to broker the deal. Hines didn't — he tore up the check, mailed the pieces back, and told him that he wouldn't be doing that under any circumstances — but the entire episode spoke volumes about just how respected and trusted he was.