The Untold Truth Of Cracker Jack

The candy-coated popcorn and peanut confection known as Cracker Jack has been around for so long — since 1893, to be exact — that there's bound to be a lot that you already know about it. For example, you've probably realized by now that it's not made with caramel, but with molasses. You're probably also well aware that the meager number of peanuts per box (per The Seattle Times and Mental Floss) predates both Frito-Lay's acquisition in 1997 (via Los Angeles Times) and Borden's, from Cracker Jack's founding families, in 1963. Furthermore, it's only to be expected that you're familiar with Cracker Jack's slogan ("The more you eat, the more you want," which, ironically, is not meant to refer specifically to the peanuts) when you consider that it's been in use since 1896 (via Immigrant Entrepreneurship).

Now, if you're a Cracker Jack superfan, you may even know that Cracker Jack launched the acting career of the late great Taxi actor, Jack Gilford. It was also name-checked in the film, "Breakfast at Tiffany's," and inspired a Pepsi branded soda that was offered for a limited time in 2021 (via Food Business News). But there is a lot that you probably don't know about this edible sort of Americana-in-a-box — and a lot that Cracker Jack and its current parent company, PepsiCo Frito-Lay, probably would rather you not know. Without further ado, here is the unvarnished, untold truth of Cracker Jack.

Cracker Jack's apocryphal origin story

In 1871, at the age of 23, a well-educated German immigrant by the name of Frederick William Rueckheim invested everything he had to his name ($200, which would have been about $4,300 in 2022, per In 2013 Dollars) in an acquaintance's popcorn stand. It wasn't because he had such a particularly keen interest in popcorn, but because he thought popcorn would sell (via Made-in-Chicago Museum). In fact, it did, suggesting that Rueckheim either had a genuine affinity for popcorn or was a natural at sales and marketing. Rueckheim took over the business after two years, bringing in his younger brother, Louis. Together, the brothers created and ran a reasonably successful popcorn and confectionery business in Chicago.

"Reliable Confections," as it was known, was still chugging along two decades later, when "something really big happened." Many maintain the "something big" was the 1893 World's Fair (known as "World's Columbia Exposition"), which took place in Chicago. This was where the Rueckheim brothers introduced molasses-coated popcorn and peanuts (via ThoughtCo.). While that may be true, others suggest this confection, billed simply as "Candied Popcorn and Peanuts," was a flop at the Exposition (via What's Cooking America). Nevertheless, it inspired the brothers to come up with their hit current formula, or something very much like it. In either case, by 1896, the public was eating up this confection now known as "Cracker Jack."

How Cracker Jack got its name ... probably

Cracker Jack was a two-decades-in-the-making "instant" success by 1896, at which point the Rueckheim brothers had also dispensed with its generic branding in favor of the snappier sounding "Cracker Jack," according to Made-in-Chicago Museum. But as with Cracker Jack's origin story, the story of how Cracker Jack got its name comes in various flavors and colors. Most versions have, at their core, one of the brothers' employees or salesmen or customers getting his first taste of the new molasses-coated popcorn and peanuts recipe and exclaiming either, "That's cracker jack" or "That's cracker, Jack!" At the time, the term, "cracker jack," was used the way the terms, "lit," "fire," or "dope" are used, in today's parlance as an exclamation of high approval (via What's Cooking America). As the story goes, the name stuck.

However, based upon an 1896 "advertorial" that appeared in the Chicago Tribune, the Made-in-Chicago Museum suggests the brothers themselves may have come up with "Cracker Jack." This might have happened after hearing a German co-worker, who had just gotten his first taste of the confection, exclaim, "Das ist ausgezeichne!" That means "This is excellent!" in English. If Frederick Rueckheim authored that advertorial, then whether true or not, at least we know what Rueckheim wanted us to believe.

How Cracker Jack got into that baseball song

Cracker Jack is "part of the baseball experience," according to Kevin Haggerty, who oversees concessions at Fenway Park in Boston (via the New York Times). It's to the point where stadiums that have tried to swap it out for, say, Crunch 'N Munch, have faced notable pushback from fans. The association between baseball and the molasses-coated popcorn and peanut confection is "undoubtedly the result" of the enduring popularity of the once-a-hit-now-a-classic baseball song, "Take Me Out To The Ballgame," according to Tim Wiles, research director for the Baseball Hall of Fame. Vaudeville singer-songwriter, Jack Norworth, wrote the lyrics in 1908, supposedly coming up with the line "Buy me some peanuts and Cracker Jacks" for the simple reason that it rhymed so aptly with the next line, "I don't care if I never get back" (via Made-in-Chicago Museum).

In other words, as genius a marketing move as it might appear, the annals of history suggest that Cracker Jack got name-checked into baseball lore purely by luck. In fact, neither Rueckheim brother was even known to like baseball (at least prior to 1908), and nor did Norworth. Nevertheless, Norworth seemed to have had an inkling that Cracker Jack was sometimes sold at ballpark concession stands. In fact, it had been since 1896 — Cracker Jack made its first appearance at a pro game one year before Norworth wrote the song.

Long live Cracker Jack!

"The way baseball stadium menus have changed in recent years, an updated verse of 'Take Me Out to the Ball Game' might include the lyric, 'Buy me some sushi and lobster rolls,' rather than peanuts and Cracker Jack," New York Times author John Branch wrote in 2009. About 13 years later, the molasses-coated popcorn and peanut confection is still sold in baseball stadium concession stands virtually everywhere, with concession managers considering it a "do-not-disturb item amid an ever-changing menu."

Cracker Jack is "part of the ballpark experience," the Times quoted Fenway Park's concession manager as having said back then. "It is still a good snack. It sells well. It holds its place in the sales mix. And it's in the song." There is no evidence that Cracker Jack's iconic stature as a baseball game staple has diminished in the last decade or so that has passed.

However, at least one professional baseball stadium in the U.S. has now banned the sale of Cracker Jacks, along with peanuts, in the interest of making the ballgame experience safer for people who must contend with the potentially deadly effects of a peanut allergy (via USA Today and Greenburgh Daily Voice). And a number of major league games have held "Allergy Free Nights," during which Cracker Jacks are never sold, per WFGR. The fact that baseball fans are so outraged is evidence of Cracker Jack's enduring association with baseball.

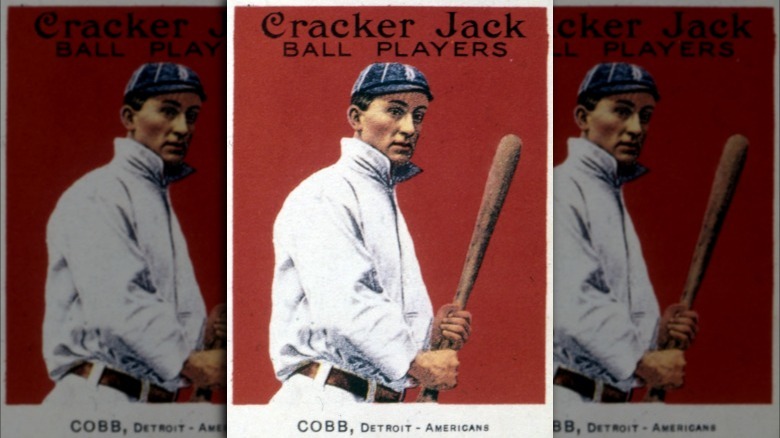

The emergence of Cracker Jack Baseball Cards

Cracker Jack's by-chance association with baseball via Norworth's classic, "Take Me Out To The Ballgame," was pivotal in Cracker Jack's success, but Cracker Jack's untold success story is a lesson in marketing savvy. When faced with the use of its brand name by Norworth in his hit song, "Take Me Out To The Ballgame," the Rueckheim brothers could have demanded royalties or some other form of quid pro quo. Had they done so, it's entirely possible Norworth would have swapped out the "Cracker Jacks" in the lyrics for something less expensive that rhymed with "never get back." However, there is no record that they ever did so.

In fact, it appears the brothers decided to "just go with it," according to the Made-in-Chicago Museum. For example, in 2014, just a few years after "Take Me Out" debuted, the Rueckheim brothers made the decision to include collectible baseball cards in every Cracker Jack box. "Many kids are most certainly familiar with the small toys included in boxes of Cracker Jack," writes All Vintage Cards, "yet it was two years (1914 to 1915) that Cracker Jack showed its true allegiance to baseball by including cards with its caramel-coated [sic] popcorn and peanuts." We'll talk more about the toys those Cracker Jack baseball cards temporarily replaced in just a bit, but those cards have become a popular — and pricey — hit among baseball card collectors (per PSA Cards).

What's at the bottom of the Cracker Jack box?

We probably don't have to tell you that "there ain't no Coupe de Ville hiding at the bottom of a Cracker Jack box," as the late Meat Loaf famously sang in his 1977 hit, "Two Out of Three Ain't Bad." But there was a time when you might have found a tiny pewter model of a convertible (via Cracker Jack Collectors), one that is virtually identical to the kind you can still move around the edges of a Monopoly game board, according to Made-in-Chicago Museum.

The Rueckheim brothers started including "prizes" at the bottom of the Cracker Jack box in 1910 as a marketing move. It started with coupons that would have appealed to adult purchasers, but by 1912, "the company was tucking tin soldiers, paper dolls, spinner toys, and other assorted kids stuff right in there with the peanuts and popcorn." As noted above, during 1914 and 1915, the surprise was baseball cards, which are worth much more today than when they were issued. The Monopoly-esque playing pieces started appearing a bit later, and in fact, they were manufactured by the same company that pioneered Monopoly's actual playing pieces.

Like Cracker Jack baseball cards, many Cracker Jack toys are now collector's items, according to Mental Floss. Parent company, Frito-Lay, permanently replaced toy prizes with QR codes, with which to access online games in 2016, per The Washington Post. As a result, those toys may become even more valuable.

The secret behind Cracker Jack's patriotic trade dress

"Don't judge a book by its cover," they say, but even "they" know that's not always how it's done (via Draft2Digital). Despite the fact that a juicy-looking "burger" could actually be cake and ugly fruit can actually taste delicious, packaging matters. It certainly did in the untold story of Cracker Jack. In 1899, the Rueckheim brothers partnered with Henry G. Eckstein, who came up with a "waxed sealed package" that would enable Cracker Jack to eventually be packaged in its now-iconic slim, red, white, and blue boxes — rather than the bulky tins in which the confection had been packaged initially.

Not that there's anything wrong with a holiday-themed tin of goodness. It's just that Eckstein's innovation meant Cracker Jack could now travel from Chicago to various points without a reduction in "freshness and crispness" (via Made-in-Chicago Museum). Eckstein's contribution was so significant to Cracker Jack that the company eventually began doing business as "Rueckheim Bros. & Eckstein."

As for the distinctive red, white, and blue that you still see on Cracker Jack boxes, the great-granddaughter of Frederick Rueckheim told Bend Bulletin in 2015 that using the colors of the American flag was a strategy the Rueckheim brothers and Eckstein adopted towards the end of World War I. They wanted to get in front of allegations of Anti-Americanism, fueled by both the prevailing anti-German sentiment and several missteps made by the company (via What's Cooking America), as discussed below.

The tragic story of the boy on the Cracker Jack box

In 1918, at the same time that Cracker Jack debuted its now-iconic red, white, and blue packaging, it also added a little boy in a sailor suit. He was on Cracker Jack boxes, and tucked under his arm was an adorable pup known as "Bingo" (although in real life, he was Eckstein's dog, Russell, according to Made-in-Chicago Museum). The adorable tableau was meant to appeal to children, as Cracker Jack's sales manager, F.E. Ruhling, wrote in a 1921 issue of Printer's Ink magazine. What Ruhling did not mention at the time was that this little boy, known as "Sailor Jack," had been modeled on the grandson of Cracker Jack founder, Frederick Rueckheim. Born in 1913, Robert Rueckheim died in 1920 of pneumonia, according to DNAinfo.

Perhaps Ruhling left that part out of the story because it felt "too soon" to speak of it. Maybe Ruhling was keeping his focus on the central point in his message, which was that Cracker Jack's decision to go with a patriotic Sailor Jack and his dog "was simply an application of the lessons of the war to business." As Ruhling put it, "morale is as important in business as in battle." And so, more than a century after his death, Sailor Jack remains on the Cracker Jack box. However, his appearance has evolved over the years, just as Bingo's has, presumably in line with the cultural tastes of the day.

The Cracker Jack child labor scandal

According to Made-in-Chicago Museum, one of the darkest chapters in Cracker Jack's history is the company's use of child labor. "Feeling under constant threat from confectionery rivals and copycats, the company used every means necessary to cut production costs while increasing output," the Museum states, adding that "this included hiring as many as 200 child laborers in the early 1900s." If you're wondering how a company that had to depend on the goodwill of families with children could have done such a thing (via Immigrant Entrepreneurship), it may be worth considering that employing child labor was not "blatantly illegal" at the turn of the 20th century — at least not with regard to children ages 14 and up.

Nevertheless, employing child labor was increasingly frowned upon at this time. In 1901, the Rueckheim and Eckstein business was ranked as the sixth-largest employer of children in Chicago, drawing the ire of political activists. By 1908, the company had halved its child labor force. That said, so did many other Chicago businesses; with its child labor force thus reduced, Cracker Jack actually rose to become the fifth-largest employer of child labor. At the same time, the company was also getting a bad reputation for its treatment of adult laborers. Nevertheless, the company survived the bad press, only to come up against the even darker specter of anti-German sentiment during World War I (see below).

Anti-German sentiment during World War I

Immigrant Entrepreneurship describes the cultural climate of the U.S. during the "Great War" as growing increasingly icy toward Germany and all things and people with ties thereto at the time. Cracker Jack founder Frederick Rueckheim, who was in his mid-60s at the time the U.S. invaded Germany's ally, Austria-Hungary on December 7, 1917 (via Office of the Historian), had a tendency to not make the situation any easier on himself, according to Made-in-Chicago Museum.

Earlier that year, Rueckheim courted some extremely negative press when, on repeat occasions, he refused to allow representatives of the military to engage in recruiting activities at one of his Cracker Jack factory locations. According to one member, Rueckheim behaved in a disrespectful manner toward his fellow militia members. According to another, when asked why he kept a photo of a German military hero on his desk, Rueckheim replied that he feels compelled to keep that photo on his desk while making Cracker Jacks "for the American nation." Still, another claimed Rueckheim refused to donate a penny to the American Red Cross.

A few weeks later, Cracker Jack's founder realized it was in his best interest to take somewhat of a different stance. In fact, he completely reversed himself, issuing a statement that closed with, "Any call made upon me by my country in any capacity will be promptly answered." Crisis averted.

The Cracker Jack revolving door

Cracker Jack would not stay in the Rueckheim family forever. In the 1960s, a buyer came calling — Borden, Inc., originally founded in 1899 in Ohio as the Borden Condensed Milk Company. At the time, Borden was on a bit of a buying spree, having purchased a seafood chowder company, a bouillon maker, a lemon juice manufacturer, a potato chip company, and, finally, Cracker Jack in 1964 (via Company-Histories.com). It also bought Cracker Jack's sister marshmallow brand, Campfire. At that time, according to the Chicago Tribune, Cracker Jack was still based in Chicago, with about 500 employees.

By the end of the 1960s, Borden's product line had stretched far beyond its original dairy industry, and even beyond food items, to include products like Elmer's glue and Krylon spray paint. With enough on its hands, Borden left Cracker Jack mostly alone, but change would come just a few decades later.

PepsiCo Frito-Lay welcomed Cracker Jack to its fold in 1997. According to the Los Angeles Times, at the time of the sale, Cracker Jack was pulling about $60 million per year in profits, and it was expected Frito-Lay would use existing resources to help boost that number further. While analysts theorized that the snack food giant paid less than $50 million for Cracker Jack, they also recognized the challenge that would come with giving new life to such a historic brand.

'Oops' moments in Cracker Jack history

Clearly, Cracker Jack founder Frederick Rueckheim made a lot of brilliant decisions, but he was not above making the occasional error. For example, under Rueckheim's tutelage in 1928, the Cracker Jack Company, as it was by then known (via Immigrant Entrepreneurship), trotted out a coconut-flecked version of the original Cracker Jack formula, marketing it as "healthful, pure, and wholesome" (via Made-in-Chicago Museum). That sound the company heard in response? Crickets, which is why you've probably never even heard of Cracker Jack's "Cocoanut Corn Crisp."

In more recent memory, under PepsiCo Frito-Lay's ownership, Cracker Jack has tried and failed to resonate with millennials with savory flavors of Cracker Jack, including "Buffalo Ranch" and "Spicy Pizzeria," going so far as to enrich some of the flavors with caffeine (via CBS News). Again, crickets. And just last year, Pepsi's limited edition Cracker Jack-flavored soda came and went, with little protest from its presumably scant number of fans. Maybe if Cracker Jack would introduce a sweeter caramel-corn version, some long-ago Crunch 'N Munch converts might come back. Not that concession managers are particularly anxious or even eager for Cracker Jack to innovate, as discussed above, via the New York Times.

Some new flavors stuck around

Not all Cracker Jack variations were total flops. In 1992, Borden decided to give Cracker Jack an upgrade, with a new flavor for a new generation. As the Chicago Tribune reported at the time, Borden created a second Cracker Jack flavor, with butter and toffee versus the traditional caramel and molasses flavor — a decision the publication called "yuppified" (via the Baltimore Sun). The prizes and peanuts stayed the same, with just the popcorn coating changing things up (plus a new look on the packaging — the red, white, and blue motif was swapped out for blue and yellow).

Today, you can find a version of Cracker Jack's butter toffee product, though it only includes the popcorn, not the peanuts. To some, though, the additional flavor was a long time coming, with one marketing expert telling the Chicago Tribune that the new flavor coming so late in the game was not "anything remarkable," saying, "By now they could have had 10 kinds of corn in addition to what they've got. If they wanted to appeal to the adult market, they could have come up with versions of Cracker Jack for cocktail parties that have olive dots embedded in the popcorn ... or a Cracker Jack trail mix for the health-conscious." Well, we now know how savory and healthy versions have worked out for the brand. Awkward.

Cracker Jack was once promoted as a health food?

In 1928, when Cracker Jack came out with its "Cocoanut Corn Crisp," it marketed those "luscious lumps of goodness" as being "healthful, pure, and wholesome" enough that you, as a consumer, should feel free to "eat as much as you like!" (via Made-in-Chicago Museum). It wasn't the first time that Cracker Jack was marketed using an inexplicable health halo. Back in 1918, after Frederick Rueckheim began behaving extra patriotically, he and his team made the decision to market Cracker Jack as a "tissue-building, muscle-making energizer," if not a fully appropriate "breakfast cereal" (via Immigrant Entrepreneurship).

Cracker Jack was promoted as the "ideal war-time food" that could be eaten as a breakfast cereal or as an afternoon "tissue-building, muscle-making" energizer. In fact, the Cracker Jack Company sought to position Cracker Jack as the "ideal war-time food," reminding customers in their ad copy that eating Cracker Jack was an act of patriotism. "Eat More Cracker Jack — Save Sugar and Wheat!" suggested one ad, which must have made sense at the time, one would think. At the present time, however, Cracker Jack's first ingredient is none other than "sugar" (via H-E-B).

The introduction of Cracker Jill

Meet the latest addition to the Cracker Jack family: Cracker Jill, introduced in April 2022.

Though it's just the same product with new packaging, Cracker Jill celebrates women in sports and swaps out Sailor Jack on each package for different variations of a new mascot, Sailor Jill. The Sailor Jill packaging is a special-edition option, Frito-Lay says, available only in professional ball parks or when consumers make a $5 or larger donation to the Women's Sports Foundation (via a special link) while supplies last. In conjunction, Cracker Jack has pledged to donate $200,000 to the Women's Sports Foundation and even hired music artist Normani to record a new version of "Take Me Out to the Ball Game" that features Cracker Jill in place of Cracker Jack in the lyrics.

While Cracker Jill's introduction was timed to coincide with baseball season, Frito-Lay intends to keep Sailor Jill alongside Sailor Jack as a fixture of the brand.