False Facts About Turkey You Thought Were True

Turkey holds such an outsized role in traditional holiday feasting that it is bound to be shrouded in mythology. There are plenty of common misconceptions surrounding the live bird. For example, despite many people believing that turkeys can't fly, the wild variety can take flight at speeds up to 50 miles per hour, according to National Geographic. They can also run up to 12 miles per hour and swim by fanning out their tails and kicking their feet. Another common misconception is that the bird comes from Turkey. Historians believe they were named after the country in the 15th or 16th century either because they were traded through Turkey on the way to England or because the English mistook them for another bird from West Africa, which also traded through Turkey (per the Washington Post).

As a centerpiece of holiday meals, turkey meat is encumbered with even more mythology, from food safety to cooking methods. Luckily, we're here to bust a few of those myths so you can take on the turkey-making duties this year worry-free. It's time to say goodbye to dry turkey, undercooked turkey, and avoidable food-borne illnesses once and for all.

Cooking stuffing in the turkey will give you food poisoning

One of the biggest concerns when preparing a turkey is eliminating bacteria. The U.S.D.A. estimates that 23% of foodborne Salmonella illnesses are the result of eating chicken or turkey, which rightfully makes many home cooks extremely cautious. One of the rules of thumb that has arisen over the years is that you should always cook the stuffing separately. Because bacteria can survive in temperatures up to 165 degrees Fahrenheit (per the U.S.D.A.) and a stuffed bird takes longer to cook all the through, it is sensible to be concerned about cooking them together. However, it is possible to do it safely, and given how delicious stuffing is when it's been absorbing all the flavor-packed fats and juices of the cooking turkey, it's worth the extra time and attention.

To safely roast a stuffed turkey, do not stuff it until right before you put it in the oven. If there is meat in your stuffing, cook it first. Check both the internal temperature of the meat and the temperature at the center of the stuffing to determine if they are done. Both should be 165 degrees Fahrenheit. If one has reached the right temperature, but the other hasn't, leave both in the oven. Lastly, leave the stuffing inside the bird for 20 minutes after removing it from the oven to allow a little extra cooking time.

It makes you sleepy

We've all been there: you've just finished the last bite of pumpkin pie, taken a final swig of eggnog, and laid your cutlery on your empty plate. As you sit back in your chair, it hits you —a wall of fatigue that sends you into a doze on the sofa. There is nothing untrue about this phenomenon; the post-feast food coma is very real. But its cause is frequently misattributed.

According to popular belief, the sleepiness you feel after the Thanksgiving meal is due to tryptophan, an amino acid found in turkey. It plays a role in the production of serotonin, a hormone that, among other things, helps regulate mood and sleep (per CNN). However, you would have to consume about eight pounds of turkey to get enough tryptophan to affect your energy levels, which is quite a bit more than most of us are eating, even on Thanksgiving. The more probable cause of the drowsiness has to do with carbohydrates. All the carb-heavy foods that fill our plates, from stuffing to pie, increase serotonin in the brain.

On top of this, Scientific American explains that eating large quantities of food enlarges the small intestine, which has been shown to cause sleepiness and draw blood flow away from the brain and skeletal muscles. Lastly, if you've been sipping an alcoholic beverage throughout the day, chances are, that's played a role in the sluggishness too.

It's always dry

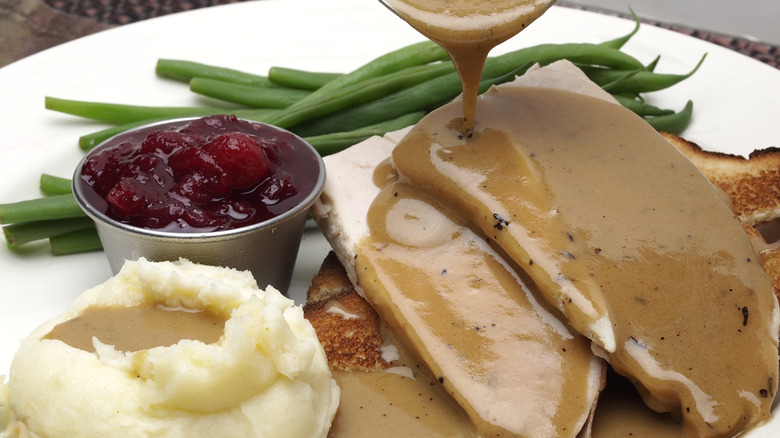

One of the goals of Thanksgiving side dishes is to soften up the main dish. Acidic cranberry sauce, creamy gravy, and bready stuffing all help to balance the toughness that so often comes with turkey. And yet, while the relative leanness of this type of meat makes it susceptible to dryness, it isn't inevitable. With a few tweaks to your recipe, turkey can be as succulent as a pork tenderloin.

There are multiple ways to increase the juiciness of your turkey. One is to buy it frozen. Unfrozen turkeys are kept at a temperature that usually hovers around freezing, meaning that they might thaw and freeze several times before you buy them. As they thaw and refreeze, the ice inside them contracts and expands. This can damage the cell membrane in the meat, leaving it dry. Frozen turkeys, on the other hand, have usually only been frozen once and will, therefore, paradoxically, taste fresher.

Making sure the bird is fully thawed will also prevent dryness. The center already takes longer to cook than the outside, and if it's still frozen, the outer part of the turkey will be dry as a bone by the time the inside reaches 165 degrees Fahrenheit. Lastly, let it sit for a good 45 minutes after removing it from the oven. This allows the juices to be reabsorbed instead of spilling out the moment you slice into it.

It's safe to thaw it on the counter

You might see advice floating around that says you should bring the turkey to room temperature because it helps ensure even cooking. In an ideal world, this would not be an issue. Unfortunately, however, there is no safe way to do this because room temperature falls squarely within the "Danger Zone," the range between 40 and 140 degrees Fahrenheit. According to the U.S.D.A., bacteria grow rapidly in the Danger Zone, doubling in as little as 20 minutes.

There are three ways to safely thaw a turkey. The most hands-off option is to let it sit in the refrigerator, though this requires planning. It will take about a day of thawing per four pounds of meat. According to Experian, the average weight of Thanksgiving turkeys in 2015 was 16 pounds, meaning you'd need to set aside four days (and plenty of fridge space) just for thawing.

Another option is to use cold water. Simply submerge the packaged bird in water below 40 degrees for about 30 minutes per pound, changing the water every 30 minutes to ensure it's cold enough. The final safe option is the microwave (provided it's big enough). Using defrost mode, aim for six minutes per pound, though you should check the manual for the greatest accuracy. Make sure to rotate the turkey several times and cover the tips of the wings and drumsticks if they start to cook.

You can trust your pop-up thermometer to know when it's done

Many Thanksgiving turkeys come with plastic timers that supposedly pop up when the meat reaches 165 degrees Fahrenheit. It's an ingenious invention that should give you one less thing to fret about as you juggle side dishes and dessert recipes. Sadly, however, these little timers can easily lead you astray.

According to a test conducted by Consumer Reports, these timers can pop up when the temperature of the turkey is as low as 139 degrees, where deadly bacteria can still thrive. Some also popped up when the meat was over 165 degrees, which, though not harmful to health, guarantees dry, chewy turkey, the bane of a Thanksgiving meal.

For best results, you need to use a meat thermometer and check multiple parts of the bird, preferably the thickest part of the breast, where the body and thigh join, and where the body and wing join. Make sure the thermometer isn't touching bone, as this can lead to a false reading. There's no reason to avoid a turkey with a pop-up timer, but you're better off disregarding it. Since they can pop up prematurely and after the turkey has reached its temperature sweet spot, they are more likely to cause headaches than cure them.

Turkey was served at the first Thanksgiving feast

The first Thanksgiving occurred in 1921 between the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag in what is now Massachusetts. Many of the illustrations purporting to depict the scene show an abundant spread with turkey at its center. However, despite the mythology surrounding the event, historians are pretty sure that turkey was not on the menu. Of the two first-hand accounts that survived, we know that the food included corn, venison, and wildfowl (per Smithsonian Mag). The wildfowl of choice was likely duck or goose, though it could have been swan or passenger pigeon, which were popular options at the time. Although we only have certainty about corn, venison, and wildfowl, the Wampanoag were known to have a wide-ranging diet that included seafood such as eel and lobster, and nuts like chestnuts and walnuts.

One of the main people we have to thank for the continuation of the holiday and its unshakable association with turkey is Sarah Josepha Hale, the editor of a popular 19th-century women's magazine. Hale petitioned 13 presidents to make Thanksgiving a national holiday and finally succeeded by convincing Abraham Lincoln that it would help heal the country's wounds following the Civil War. Her recommended recipes for the occasion included turkey, mashed potatoes, and creamed onions, which remain popular choices for the holiday.

You should wash the turkey before cooking it

Poultry is known for its susceptibility to harmful bacteria like Campylobacter and Salmonella, so it stands to reason that you should be just as diligent about washing it as you are about washing your hands after a subway ride or using a public bathroom. But experts say this is not the case. In fact, washing poultry can have the opposite effect, spreading dangerous germs around your kitchen as if you were doing it intentionally.

When the U.S.D.A. conducted a study to assess the risks of washing raw poultry, they found that 60% of the participants had bacteria in their sink after rinsing the meat, while 14% had bacteria even after washing the sink. The study also found that 26% of participants who prepared salad after washing raw poultry transferred bacteria to the greens.

It is frighteningly easy to spread germs by washing turkey, but the good news is that it is easily avoided: just don't wash it. Meat manufacturers wash poultry so that you don't have to, and the only thing that will effectively kill the harmful bacteria that cause food-borne illnesses is heat. As long as you cook the meat to 165 degrees Fahrenheit and serve it shortly thereafter, you don't have to worry about germs. If you see anything on the meat that looks suspicious, wipe it with a damp paper towel and then wash your hands thoroughly.

Basting the turkey keeps it moist

Basting a turkey feels professional. Basters look like they're one step removed from a scientific instrument you'd find in a test kitchen, while brushes look like the tools of a gastronomic artist. From a practical standpoint, basting also seems to make sense: if you want a moist turkey, you should drench it in butter or drippings from the pan. However, common sense does not always apply when it comes to cooking, and basting is one such example.

Turkey is not a sponge. Unlike, say, toast, it does not absorb every ounce of butter or broth that you throw its way. The moisture just slides off. The fatty liquid that you see at the bottom of your pan on the third baste isn't the natural result of cooking a turkey–a large proportion of it is the butter that you thought was making its way through the layers of meat like rain being thirstily soaked up by parched soil. Basting merely results in a greasy puddle at the bottom under your turkey and, tragically, rubbery skin. It also extends the cooking time since all that opening and closing of the oven door leads to temperature loss. If you want moist meat and crispy skin, you're better off brining it.

White meat is healthier than dark meat

White or dark meat? It's the inevitable question you'll hear when you pass your plate for a helping of turkey. If you're counting calories, you'll probably instinctively ask for white meat (breast and wings) because it has fewer calories than dark meat (thighs and drumsticks). Although the latter is known for being more flavorful, it is also higher in saturated fat, which has given it the reputation of being less healthy. For years, light meat was the most popular option, but between 2009 and 2019, consumption of chicken thighs increased ninefold (per the Los Angeles Times). This is probably due to its superior flavor, but there is also a case to be made for its health benefits.

100 grams of roasted turkey thigh meat has 165 calories and 6 grams of fat compared to 147 calories and 2 grams of fat in roasted turkey breast meat. However, it also has significantly more micronutrients, including iron, B vitamins, and zinc. Compared to marshmallow sweet potatoes, buttery stuffing, and creamy mashed potatoes, dark turkey is basically a health food, providing essential nutrients on top of all the flavor.

The turkey is cooked when its juices run clear

Figuring out when the turkey is done is one of the main anxieties cooks encounter when preparing their Thanksgiving meal. The line between partially raw thigh meat and leathery breast meat can feel awfully fine when you're agonizing over whether to pull it from the oven, and you'll happily welcome any sign that will tell you exactly when it's ready. One of the tips you've probably seen at some point is that the turkey is done when its juices run clear. While there is some truth to this piece of advice, it is not a safe indicator of doneness, and following it without verifying the temperature with a meat thermometer could leave you with raw turkey.

The juice that flows out of an undercooked turkey is, like the raw meat, a pinkish hue. As the bird cooks, the color will disappear, but it does not correlate to 165 degrees Fahrenheit, the temperature at which the meat is cooked and the bacteria are killed. When the juices run clear, the only thing you can say for sure is that the turkey is cooking, not that it's done. The only safe, reliable way to determine doneness is a meat thermometer.

Brining is an unnecessary hassle

Brining is the process of soaking the whole turkey in saltwater before cooking it to maximize flavor and moisture. It has a reputation for being time-consuming and labor-intensive, and many recipes skip it altogether. But it has major benefits and doesn't have to be as inconvenient as it's made out to be.

Salt is the key ingredient in brine, making the coils of protein in the meat unwind and become more porous through a process called denaturing. As the turkey cooks, the protein fibers contract, but because they have been denatured, they do not contract as tightly, meaning that less moisture in the turkey is compressed out. The result is salty, deliciously juicy meat.

Traditional brining involves submerging the entire turkey in saltwater and refrigerating for at least 12 hours. It can be difficult to find a container large enough, and splashing contaminated water around your kitchen is less than ideal. If this all seems a bit fussy, there is another option that produces similarly succulent results: dry brining. The water component in brine plays a secondary role to the salt in making the meat juicy. Turkey has plenty of internal moisture already, and the key is, therefore, to prevent it from escaping rather than adding more. Covering the turkey in dry salt and letting it sit for 12 to 24 hours in the fridge allows the fibers to denature without the hassle of soaking it in water.

You have to cook the turkey whole

When you imagine a Thanksgiving table, the centerpiece is most likely a turkey, whole and perfectly roasted, with crispy browned skin encasing the juicy meat. It's the starring player around which every other dish revolves. Without it, the meal would have an identity crisis where everything and nothing was the focus of the table. The mere suggestion of serving a deconstructed turkey feels wrong, but what if it's actually the answer to all your turkey-related problems?

No matter how carefully you prepare your bird for the oven or how often you check its internal temperature, it will always be a little bit overcooked in places, or worse, undercooked. This is because different parts of the turkey cook at different rates. White meat only needs to reach 145 degrees Fahrenheit (for a minimum of eight and a half minutes to kill the bacteria) before it tips into dryness, while dark meat remains raw until it reaches 165 degrees. There is nothing you can do about this. But if you cook the turkey in pieces, you can ensure that each part of the bird is cooked to perfection. You may not have a platter bearing the traditional Thanksgiving centerpiece, but you can get creative with how you arrange the separate parts, and let's face it: the moment your guests taste the perfectly cooked meat (white and dark), they'll forget about everything else.