Everything You Need To Know About Wet-Aged Steaks, According To Chefs

Dry-aged steak is all the rage, omnipresent on the menus of some of the world's top steakhouses. But what about wet-aged steak? This more modern process stands out from dry-aging in a number of ways. Rather than relying on an aerated space to promote moisture loss and enzyme activity, as dry-aging does, wet-aging takes place in a sous-vide sealed plastic bag, which is held under refrigeration for a few days or even a couple of weeks with the goal of improving the meat's flavor and texture.

"What happens during the wet-aging process is the chemical breakdown of the muscles," explains Katie Flannery, one-half of the father-daughter pair behind Flannery Beef. The resulting steaks, she says, don't have the funk of dry-aged; instead, they tend to taste more of themselves.

For Amy Morton, owner-operator of AMDP and daughter of famed restaurateur Arnie Morton, the question of whether to choose dry- or wet-aged steak is down to personal preference. "To me," she says, "it's not about what's appropriate, it's about the flavor profile and price point someone is looking for." The best way to choose, then, is to understand the difference; with that in mind, we've tapped a host of top steak chefs to explain exactly what makes a wet-aged steak stand out.

Wet-aging engages natural enzymes in the beef

Wet-aging essentially works by controlling the breakdown process that beef undergoes naturally beginning at the moment of slaughter, Flannery explains. "After slaughter," she says, "there is no energy source for cells, the animal's tissue can no longer maintain homeostasis, and essentially the lack of blood flow is what turns muscle into meat."

At this point, according to Executive Chef Andrew Lim of Chicago's Perilla Korean American Fare, enzymes begin to do the work to break down protein and sinew in the meat, much as they would when dry-aging.

"Because those chemical reactions are taking place within the muscles," explains Flannery, "they don't care if the primal is kept in a vacuum sealed (anaerobic) environment or kept in a cooler exposed to air (aerobic environment)."

This process continues, according to Flannery, for as long as the enzymes responsible for the breakdown remain alive; once they die off, the steak is wet-aged to perfection and should be quite a bit more tender than its fresh counterpart would be.

Wet-aging takes less time than dry-aging

Much like dry-aging, wet-aging can be done for a wide range of time, with a minimum, according to James Wright, Executive Chef at Klaw, of about 14 days — far shorter than dry-aging, which, he says, typically is done for a minimum of 30 days — and may stretch to several months.

"The process is much shorter than the dry-aging process," echoes Lim, who notes that two weeks is ideal for wet-aging; Bob Broskey, Chef-Partner of RPM Steak, notes you can go as far as 28 to 36 days. But don't go assuming that the longer you wet-age, the more tender your steak will become. Flannery says this is far from the case.

"It's not a linear process," she says. "Eventually the process halts altogether because the enzymes responsible for the breakdown die off."

Most studies, she says, show that softer cuts like ribeye, New York strip, or filet will improve for about 28 days or so; after a month, she says, change has proven to be minimal and therefore not worth the time or space required. And that's not the only reason you don't want to wet-age beef for too long, she says.

"The other concern with longer periods of wet-aging is that you will see a buildup of lactic acid when the meat is in a vacuum-sealed package for extended periods of time," she says, "and this can contribute a metallic / slightly sour undernote to the flavor of the meat."

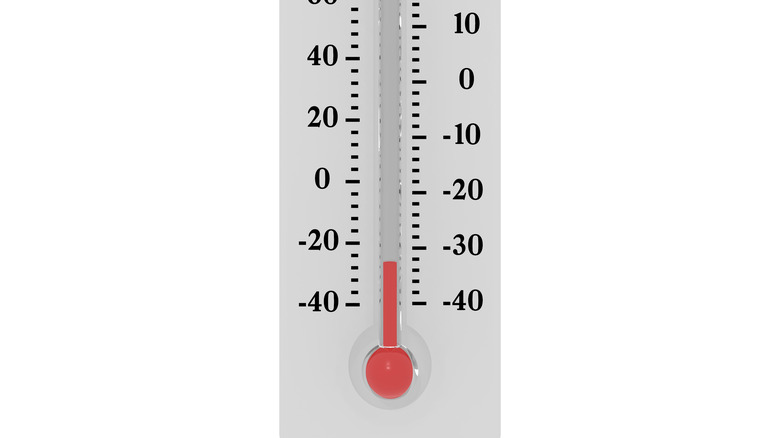

Wet-aging needs to be done at specific temperatures

Wet-aging and dry-aging also differ as far as the ideal temperature is concerned. Wet-aging, according to Chef Debbie Gold, James Beard award-winner and executive chef and partner at AMDP, is ideally done at the temperature of a typical fridge, usually around 28 to 35 degrees Fahrenheit. Dry-aging, meanwhile, is best carried out at slightly higher temperatures ranging from 34 to 41 degrees, she says.

Of course, there is some wiggle room. Lim narrows the field slightly, saying that wet-aging should take place at approximately 30 to 35 Fahrenheit and dry-aging at between 34 and 40 Fahrenheit. And Broskey adds that they can even happen at the same temperature.

For Flannery, the most important thing is that either technique be used below 44.6 degrees to prevent the development of dangerous pathogenic bacteria like E. coli. "It's ultimately up to the supplier what temperature to keep their coolers at, as long as it's below that threshold," she says, noting that the difference in temperature will not change the chemical wet-aging process.

Wet-aged steak is less expensive than dry-aged steak

As opposed to dry-aged beef, which loses weight as it ages, wet-aged beef retains its full weight during the process. This, Flannery says, is due to the anaerobic environment in which it takes place. "There is no way to lose moisture (like you do in dry-aging)," she says. "It's trapped in the bag."

This moisture retention is perhaps the most important difference between the two processes — and contributes notably to the price discrepancy between dry- and wet-aged beef that, according to Flannery, can be "dramatic." She gives the example of a 20-pound bone-in ribeye, which will lose about 10% of its weight to evaporation alone and even more when it's trimmed before selling or serving. "After the moisture and trim loss incurred from dry-aging," she says, "you effectively paid $14.28/lb, not $10/lb."

And for Lim, that's not the only reason dry-aged beef is more expensive. Dry-aging beef, since it takes place at a higher temperature, incurs more risks — and the potential for expensive losses. As a result, the price of the product is far higher than that of wet-aged beef, which is way more accessible for most.

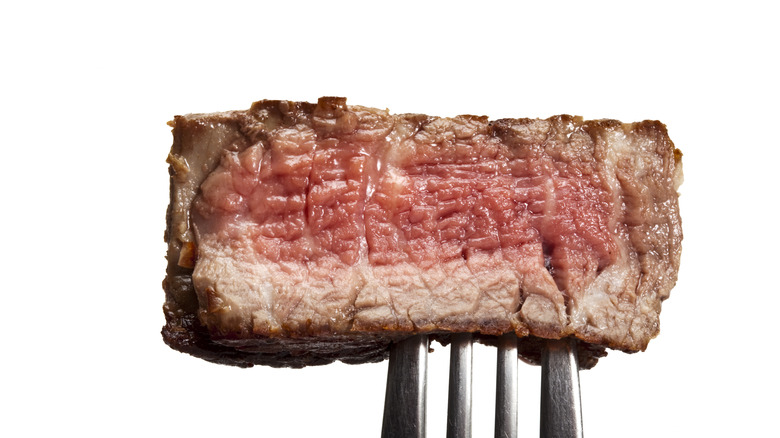

Wet-aging steak intensifies its natural flavors

Dry-aged beef is known for taking on slightly funkier flavors, which Morton describes as musty or almost cheese-like and Lim dubs nutty and earthy. But this flavor transformation doesn't happen with wet-aged steak, which, Lim says, "retains the 'fresh' meat flavor."

For Flannery, since most beef sold in the U.S. is wet-aged, these flavors are far more familiar to most consumers. Indeed, if wet-aged beef undergoes a flavor change, it's usually a bad sign.

"In dry-aging, the flavor changes (mostly) due to two things: The evaporation of moisture from within the meat, and microbial growth on the exterior of the meat," she says, noting that the longer one dry-ages a steak, the more intense these flavors will become. When a wet-aged steak changes flavor, she says, it's mainly due to the buildup of lactic acid, which can give it metallic or off flavors.

On the contrary, properly wet-aged steak just tastes more like itself, according to Morton. "Dry-aging changes the flavor, some would say enhances, others exaggerates," she says. "Wet-aging is the ultimate in setting the true beef flavor profile and bringing it to life!"

Wet-aged steak is more tender than fresh steak

Wet-aging may not transform its flavor much, but it does have an effect on its texture. "Wet-aging is all about the tenderness of the beef," says Broskey. This, Lim says, comes from the enzyme breakdown of the protein, leading to a more tender piece of meat.

But for Flannery, it's important not to ascribe dramatic powers to this process. While the cellular breakdown certainly tenderizes meat a bit, "it only enhances tenderness to a certain degree," she cautions.

"Wet-aging isn't a magic solution that will turn a tough cut into a tender cut," she says. "No amount of wet-aging will turn a cut from the top sirloin into something as tender as the filet mignon steak."

With this in mind, she notes, the steaks that most benefit from wet-aging are ones that are already a bit on the tenderer side. "Cuts that tend to be much tougher by nature, though they will tenderize slightly through the wet-aging process, will still ultimately end up being categorized as 'tough', and might not make the added time required worth it," she says.

For Morton, this is far from a bad thing. On the contrary, wet-aging's effect on texture is similar to its effect on flavor: magnifying the qualities already present. "To me, it protects the texture," Morton says. "It is what we imagine when we think of the perfect bite."

Wet-aging is best for leaner cuts

As opposed to dry-aging, which, Wright asserts, is a technique best applied to steaks like ribeyes that have a protective layer of fat and bone, wet-aging is best suited to leaner, boneless cuts like tenderloin, skirt steak, or blade steak. This, Lim says, is because wet-aging retains the moisture in the meat by its very design. Since leaner cuts have a tendency to lose moisture, wet-aging is far more to their advantage than dry-aging, which may result in a dry steak.

"For a cut with nice marbling, the moisture loss is mitigated by the marbling which still keeps the end result tender and flavorful," explains Gold of dry-aging. "For a lean cut though, you both lose moisture and you have little to no intramuscular fat to make up for it, so you wind up with little more than dry protein, like an overcooked chicken breast."

Wet-aging is useful for tenderizing lean game meats

It should come as no surprise to those familiar with game meat that the tenderizing effect of wet-aging, especially with leaner cuts, makes it the ideal technique to use. Indeed, Broskey recommends wet-aging elk or even bison; Lim echoes these recommendations, noting that the already-flavorful, leaner cuts do well with this technique. "The best game meat that is suited to wet-aging is venison," asserts Wright. "With it being a lean meat, it benefits from the wet-aging process."

Flannery notes that the innate toughness of game meat is part of what makes this technique so useful. "Game is inherently more tough than fed cattle," she says, "so any additional tenderization that you can achieve through wet-aging would be a good move."

If you're a hunter, wet-aging could be the thing that takes your game to the next level, but Morton cautions that this doesn't necessarily apply to game birds, which would only intensify in flavor — potentially unpleasantly — with this technique.

Wet-aged steaks are better with sauces than dry-aged steak

Given the added flavor dry-aging imparts on meat, a dry-aged steak is usually best without any flourishes or added accouterments — and that means sauces.

"As a dry-aged cut has a pungency, the sauce would need to stand up to it," says Morton, and Wright notes that the more "robust" flavor of dry-aged meat is a more difficult pair with assertive flavors like those present in many classic steak sauces like béarnaise or au poivre.

Flannery agrees. "Personally I believe dry-aged steaks should be paired with nothing more than simple seasonings, to allow the flavors developed during the dry-aging process to really take center stage," she says. A bit of salt is all you really need to make a good dry-aged steak shine.

So when should you stir up a classic steak sauce? With a wet-aged steak, of course. Wet-aged steaks' innate neutral flavor means, according to Broskey, that they marry particularly well with added flavors like those imparted by sauces. "Since the point of wet-aging would be to enhance tenderness (rather than develop flavor)," adds Flannery, "wet-aged steaks are more of a blank canvas that can be paired with a myriad of sauces."

Wet-aged steaks benefit from cooking styles that impart more flavor like grilling or smoking

Seeing as wet-aged steaks pair better with flavorful sauces than dry-aged, it should come as no surprise that they also fare well with cooking methods that impart more flavor. "Wet-aged steaks are better with cooking styles like grilling and smoking as the steak has a milder flavor than its dry-aged counterpart," explains Wright, "so the grill and smoke flavor are easier to impart on the cut of meat."

But outdoor cooking methods aren't the only ones that show off wet-aged steak to its best advantage. Broskey notes that slow cooking is a great way to prepare wet-aged meat, and larger roasts like prime rib fare well with this technique.

That said, some experts say that there's no real reason to draw a line between dry- and wet-aged steak when it comes to the method of preparation. Andrew Lim says, "I personally haven't found a noticeable difference in how you prepare the steaks. You can achieve great flavor and peak deliciousness as long as you understand the proper technique."

Wet-aged beef is easier to cook properly

One difference you may encounter in cooking dry- and wet-aged steak is how you determine doneness. A dry-aged steak has less moisture than a wet-aged one, and as such, Flannery notes, it may not respond as well to a simple "finger test," a time-honored way of testing steak for doneness. The idea is simple: If you touch the fleshy part at the base of your thumb with your hand opened and relaxed, the texture should feel not that dissimilar to that of a raw steak (Try not to think too hard about why). If you touch your thumb and index finger together and touch the same part of your hand with your other finger, you'll have an idea of what rare meat will feel like. Touch your thumb to your middle finger, and you'll have medium-rare, and continue to your ring finger or pinky if you're looking for medium or well-done respectively.

Dry-aged steak doesn't respond the same way to this tactile test, according to Flannery. "It can be tricky to determine the doneness of steaks if you aren't using a thermometer, because the more moisture that has been removed from the steak during the dry-aging process, the more firm the steak will become," she explains. "You can get tricked if just poking the steak with a finger to determine if it's ready or not, and be fooled into thinking an extensively dry-aged steak is finished before it really is."

Wet-aging is easy to do at home

Dry-aging is typically done by professionals, though some tech-minded home cooks have started trying their hand at it at home. That said, Flannery notes, while it's "technically possible to do at home," safely dry-aging beef at home requires quite a bit of investment. "It should be done in a dedicated fridge, with additional air flow, and some type of temperature monitoring control to ensure safe temperatures throughout the entire process," she explains. "Additionally, if you're looking for the unique flavors that certain types of mold will impart; those molds are like sourdough starters, they take a long time to develop in the aging coolers, they don't appear overnight."

Wet-aging at home, on the contrary, is far easier, provided you've already got a vacuum sealer. All you need to do, Wright explains, is vacuum-seal your steak in a bag and keep it in your home refrigerator at its normal temperature. Be sure to check it every few days, he cautions, to ensure that it's still got an airtight seal. "If it's not," he says, "it needs to be re-sealed air tight or used as an un-aged meat. If this step is not done, at best it can lead to unpleasant flavored meat at worst it becomes rancid and inedible."

When done properly, on the contrary, you can reap all of the benefits of tenderer steak that tastes even meatier than its unaged counterparts.