What Exactly Are Juneberries?

If you want to serve a popular fruit at a meal, you can't go wrong with berries. They're a spring and summer favorite that many people look forward to having each year, and they're easily eaten fresh or cooked and baked into any number of pies, cakes, and jams. But the berries you typically see in the market in the U.S. aren't the only berries out there. The juneberry is a North American native that's well-known to foragers but that hasn't yet made a huge commercial splash outside of Canada. But it is starting to get more visibility for several reasons.

Not only does the juneberry taste great and bake up well, but it may have some medicinal benefits. It's also one of a number of foods indigenous to North America that people are beginning to focus on as they learn more about what's been growing here long before modern supply chains were formed. Whether you call them juneberries or know them by another name — and there are plenty of names for this small fruit — you'll likely agree that they deserve more attention.

What are juneberries?

The juneberry, also commonly called the serviceberry or shadbush berry, is a small fruit that grows in loose clusters on bushes or trees, depending on the exact species. They look very much like blueberries, with ripe juneberries being bluish-purplish, round, and with a crown on the non-stem end. However, they aren't berries in the same way blueberries are; they're pome fruits, similar to apples and pears. That crown you see is more closely related to the small bunch of leaflet-like things you see at the bottom of an apple or pear than it is to the crown on a blueberry. That said, juneberries are so similar to blueberries that getting super specific about the berry's botanical type doesn't change how the berries can be used.

Juneberries have one seed in their core, instead of several tiny seeds like you find in other berries. They've long been a staple food for Indigenous and other communities for centuries and continue to be one of the best fruits you can find while foraging. A healthy juneberry plant is usually an abundant producer and a welcome sight for people looking to bring home a substantial number of berries. Juneberries are slowly gaining more and more fans in the United States but are already extremely popular in Canada.

What do they taste like?

You'll find that people have different opinions on how the berries taste. The taste of the fruit itself has been described as everything from a combination of blueberries and peaches to dark cherry to raisins. The flavor is subtle and sometimes isn't easy to detect, which is why anyone buying or growing the berries should look for cultivars known for better flavor. Ripening helps the flavor stand out, of course. If you've never had juneberries before and manage to get some, try them on their own, fresh, to get an idea of what they really taste like. If you get some that you think are bland, give the berries another chance and try a second batch from another bush or farm. Then you can start baking and cooking with them and seeing how their flavor blends with whatever they're mixed with.

One flavor that many people detect is an almond-like flavor, or something like marzipan. This comes from the seeds and from a compound called benzaldehyde. In the fresh berries, this flavor is almost a hint or aftertaste. But when the berries are cooked, the almond flavor is supposed to become much more noticeable, and the scent of almond appears as well.

How do you eat or use juneberries?

Even though the berries are more closely related to apples and roses than to blueberries, you can use juneberries almost exactly like that similar-looking blue fruit. Eating them fresh is one of the best uses or you can freeze them for later. Make them into jams and jellies, pies, cakes, muffins, tarts, you name it. If you've got a food dehydrator, then you can dry the berries too. The berries can be made into wine or even a form of berry cider.

The only real issue you have to look out for when you use juneberries is that they contain less water than blueberries. That means that if you're hoping to have some of those berries break open when making a sauce or pie, and letting that juneberry juice out, you can't count on them releasing as much moisture as blueberries would. The reduced moisture also means that frozen and thawed juneberries aren't going to bleed into cake and muffin batter, so you'd need to take this into account and adjust recipes accordingly.

Where can you find juneberries?

Wild juneberries grow in an astounding number of places, and this plant and all its species cover a larger portion of North America than many realize. But if you're not into foraging, then where can you find the berries? If you're in Canada, you can find them in markets, but if you're in the U.S., you're not going to have an easy time finding them. Growing juneberry bushes and trees is the best way for many people to access the fruit, and luckily, there are quite a few cultivars that allow gardeners in diverse regions to plant and harvest the berries. Occasionally the trees show up as street trees, especially in Canada, where devoted fans on Reddit post sightings of the trees producing berries.

For those who don't want to, or can't grow the plants themselves, local farms may have the berries in regions where the plants grow well. The Cornell Small Farms program from Cornell University has been promoting juneberries to smaller commercial operations. Cornell Cooperative Extension also lists a few U-Pick farms in New York for those who are willing to pick the berries but who'd rather not go and forage for the wild stuff.

Are juneberries having a moment?

It is fair to say that juneberries are having a moment right now, even though researchers have been looking at juneberries to find potential medical benefits for a few years. The juneberry is a very common agricultural product in Canada and often sells out commercially, but in the U.S., the plant has mainly been one of interest to foragers and those who want something interesting and unique for their garden. However, in 2023, Red Bull announced that its Summer Edition energy drink would be "Juneberry," with a flavor that combined juneberries, cherries, red grapes, and red berries, giving the berry national commercial exposure both as a drink and as a slush flavor at Sonic restaurants.

Agricultural extensions and farms have tried putting the berry in the spotlight for U.S. consumers to see whether they'd buy and eat juneberries in the same way they do blueberries or raspberries. They've also suggested juneberries to home gardeners who are having trouble growing other berries as the juneberry is often easier to grow. So, the berry hasn't exactly taken the U.S. by storm, but it has been getting more attention over the past couple of years. Repeated surveys by universities and farms also show that consumers tend to be positive about the berry for the most part. Some consumers have singled out the seeds and the overall texture as negative qualities.

Why do juneberries have so many different names?

Juneberries are also called serviceberries, sarvisberries, shadbush berries, chuckleberry, and a number of other names. These names are usually based on some seasonal or regional quality that the berries became associated with. For example, the berries usually appear in June, hence the most common name, "juneberry." Some solemn legends tell of the berries heralding when roads were good enough for clergy to travel, and others claim the plant indicated when the ground had thawed enough to dig graves, hence the name "serviceberry." "Sarvisberry" may be a variation of serviceberry, and shadbush and shadblow refer to the berries appearing when the fish known as shad return to spawning grounds.

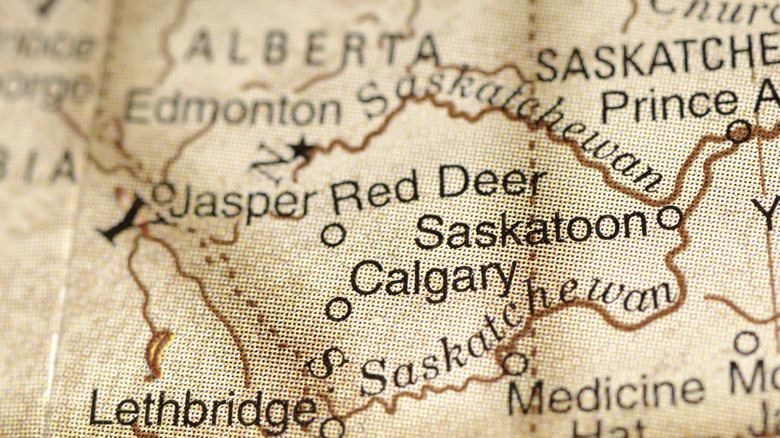

The berries are also known as saskatoon berries, with a lowercase "s." "Saskatoon" derives from a Cree word for the berries, and the city of Saskatoon in Saskatchewan, Canada, is named for the berries (and not the other way around). You may hear even more regional names for the berries as you look for them.

Do juneberries have different varieties?

A few related species are known as juneberries or serviceberries. Two species widely found across the continent are Amelanchier alnifolia and Amelanchier canadensis. Another is Amelanchier laevis, often grown into a tree shape and used as a windbreak. Others include A. alnifolia var. semi-integrifolia and A. arborea. These species differ in qualities such as size and preferred growing zones or regions.

Plants usually have a couple of varieties or more, especially if the plants are cultivated; plant breeders are continually trying to create cultivars of many plants that are hardier and more resistant to threats like drought, pests, and diseases, as well as ones that produce bigger and tastier fruit. Juneberries are no exception, with several cultivars known for different features. Several A. alnifolia cultivars are known for their size and taste, such as Honeywood juneberry, Pembina juneberry, and Success juneberry. Shannon juneberry and Indian juneberry are prolific producers, and Altaglow (this is sometimes written as "Atlaglow") is an ornamental juneberry cultivar.

How nutritious are juneberries?

Juneberries overflow with vitamins and minerals, even beating out those superfood blueberries in some cases. The berries have a substantial amount of iron (twice as much as you'll find for blueberries, according to Cornell University), magnesium, and potassium, as well as amounts of biotin and other B vitamins, plus vitamins A, E, and C. They've even got some protein, calcium, and fiber. If you want to snack on something sweet, juneberries are a terrific choice.

An interesting survey by the Cornell Cooperative Extension found that children and teens 16 and younger, plus women under the age of 26, were the most likely to really like juneberries. The older the person sampling the berries, the more likely they were to complain about texture and taste, although learning about the nutrition in the berries mitigated the dislike somewhat. That doesn't mean you shouldn't try the berries if you're older; the overall reception in the survey was very positive, regardless of age.

Juneberries do contain sugar, of course, and their lower moisture content means that they're more caloric than blueberries. But "more caloric" is relative. A cup of blueberries contains about 85 calories, and a cup of juneberries contains about 95 calories. That's not a bad trade-off considering the additional nutrition you'd get.

Can you grow juneberries?

If you live in a cool enough climate, you can definitely try and grow juneberries. Remember, these things grow wild in several U.S. states and in Canada without human help, so growing them in your home garden is possible as long as you can find the right cultivar for your environment. And some of those cultivars can grow in rather warm areas; you can find varieties for zones two through nine.

The biggest issues for juneberry trees are drought, late frosts, and some diseases and pests. Juneberries want water and aren't that tolerant of drought, and given that they grow best in cooler climates, excessive heat is not their friend. Late frosts can kill flowers and fruit, so you'll need to take protective measures to ensure a bountiful harvest of berries. Birds like to eat the berries, so you may need to add netting to the plants to protect them. Diseases and pests like cedar rust and lace bugs are also common threats to juneberry trees so you would need to take this into consideration.

How to store juneberries

Juneberries continue to ripen after being picked, so how you store them depends on how soon you want to use them. First, if you've picked a bunch of almost-but-not-completely ripe ones, leave those out at room temperature and check on them daily; you should notice the berries turning more purplish within a day or two. Do not do this with berries that have broken skin; a cut or tear in the skin is equivalent to cutting into the fruit, leading to spoilage unless refrigerated.

You're best off storing fully ripe berries in the refrigerator for three reasons. One is that your home's "room temperature" may not be that cool in June depending on where you live. The second is that ripening doesn't stop, and berries left on the counter will quickly become overripe. The third is that you probably aren't going to inspect every berry for broken skin, especially if you bought them instead of picking them one by one. Put them in the refrigerator from the start.

You can also freeze the berries. Wash and dry them first, and then spread them out on a parchment-covered tray in the freezer. Once they're frozen place all of them in a freezer bag. One of the best things about juneberries is that they don't become mushy when thawed. Canning whole or cut berries isn't recommended, but you can make freezer jam with them.

Do juneberries have medicinal uses?

There are obvious nutritional benefits to eating the berries themselves and using juneberries to prevent scurvy was common in both Indigenous and colonial communities. Juneberry leaves and root bark have also been used in Indigenous medicine for conditions as diverse as menstrual problems, post-childbirth treatment, disinfection, toothaches, and treating fevers and the flu.

While juneberries aren't as well-researched as other fruits like blueberries, there have been a number of studies looking at juneberries (these studies often call them serviceberries instead of juneberries) and their potential medical benefits like antioxidant and antidiabetic properties. The berries have shown promise as a potential functional food due to their relatively high phenolic and anthocyanin content, which may help prevent certain cancers and other diseases. However, like other highly nutritious fruits and so-called superfoods, juneberries aren't a cure-all that will make you healthy on their own. They are, however, a delicious part of a healthy diet that can be enjoyed in many different ways.

A warning about juneberry plants

Almost all parts of the juneberry plant contain cyanogenic glycosides, which are compounds that form cyanide when exposed to certain digestive enzymes. These may sound familiar; they're the same compounds found in things like apple seeds. Some sources say the berries themselves don't actually contain cyanogenic glycosides when fully ripe, but others say they do (although you'd have to eat a tremendous amount of juneberries to feel any effect). In either case, avoid unripe berries, and don't go overboard eating mass quantities of ripe berries in one sitting.

While they pose little risk to humans, the cyanogenic glycosides are dangerous to cattle, goats, and sheep, which may try to eat the leaves, stems, and unripe berries. That's not much of a concern if you're buying or foraging for juneberries, but if you plan to have a garden full of the bushes and live in a rural or semi-rural area where people keep these animals, it is something to be aware of. These animals — and any animal with a rumen — are very efficient at converting cyanogenic glycosides into their cyanide form, resulting in illness and even death. You will also need to be careful if you have a dog, as according to the USDA's Ask Extension website, unripe juneberries could make a dog sick.