The Story Behind José Cuervo (Hint: It's Not Just A Mexican Tequila Company)

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

José Cuervo is the top-selling tequila in the world, and since a massive amount of tequila is consumed in America, the name is instantly recognizable. The history of the man behind the name, however, may have been lost if not for two-time James Beard Award-winning author Ted Genoways, who spent a decade researching the details for his 2025 book, "Tequila Wars: José Cuervo and the Bloody Struggle for the Spirit of Mexico." In an interview with The Takeout, Genoways elaborated, "Even locally, José Cuervo had disappeared ... It's an odd circumstance that someone so famed should also be so unknown, but that's a big part of what sparked my interest and kept me going through years of research."

The company has been producing tequila for more than 250 years, and the history of the brand is inseparable from that of tequila. José Cuervo Labastida, the man whose name is inscribed on the bottle, was just one steward of the company, but he steered it through some of the most difficult years. Under his leadership, the company weathered the long rule of Porfirio Díaz and survived the bloody years of the Mexican Revolution. It was a dangerous era, and Cuervo's soft-spoken demeanor and preference for negotiated solutions over violent clashes stood in stark contrast to many of the figures of the time. Genoways' research reveals a complex and powerful man who played a vital role in the evolution of Mexico.

The town that birthed tequila

Tequila is a small town in the west-central Mexican state of Jalisco, a region that extends from central Mexico to the Pacific Ocean. It includes the popular tourist destination, Puerto Vallarta. In addition to tequila, the state is also famous as the birthplace of mariachi music. There are strict laws regulating where tequila can be produced, and 90% of the world's supply still comes from Jalisco.

Tequila's landscape is dominated by a dormant volcano whose past eruptions created a mineral-rich soil that is ideal for growing the blue agave plants that tequila is made from. The town is part of the story behind tequila's iconic name, but the roots extend thousands of years deeper into history. Indigenous people of Mexico made a fermented drink called pulque from the sap of agave plants that had an alcohol content similar to beer. But when Spanish conquistadors arrived, they brought European distilling methods that transformed the beverage.

Although the region provides optimal farming conditions, the geography presents challenges to distribution. In "Tequila Wars," Ted Genoways described a grueling 40-mile journey through the words of Cuervo's niece, Lupe, who documented a trip she made by carriage: "The journey from Guadalajara to Tequila was a long and painful undertaking for us ... because the royal road had several stretches that were the stuff of nightmares." Overcoming the distribution challenge was a key objective for Cuervo throughout much of his life.

The tumultuous world of José Cuervo

José Cuervo was born in 1869, four years after the end of the American Civil War, and died in 1921, potentially as the unintended victim of an assassination. Although the business was more than 100 years old when Cuervo assumed leadership, it was facing existential threats that required a steady hand to guide it through the dangerous times and avoid a total collapse.

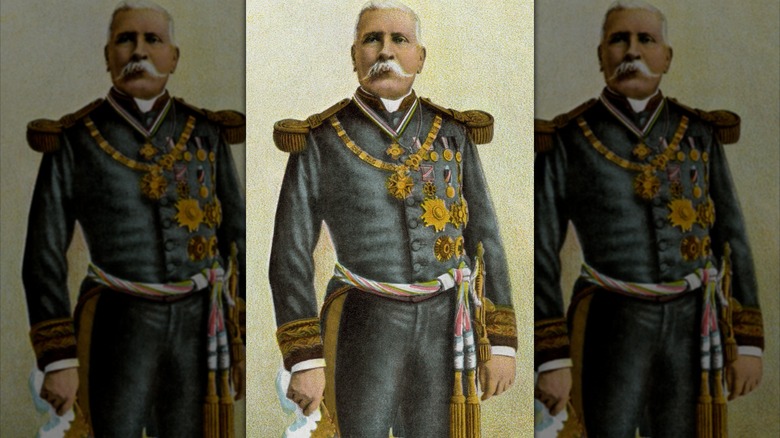

For most of Cuervo's life, Mexico was ruled by the de facto dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz, who was elected president in 1877. Despite campaign promises not to run for re-election, Díaz consolidated power once he was in office and effectively ruled Mexico until 1911. During his long reign, American industrial tycoons of the Gilded Age swooped in to buy (some would say plunder) Mexico's rich natural resources. Wealth was concentrated in the elite circle of Díaz's supporters, and the immense economic inequality helped sow the seeds of the Mexican Revolution that raged toward the end of Cuervo's life.

The threats that Cuervo faced were local as well as global. His family was one of several tequila producers in Mexico, and their main competition came from another recognizable name, the Sauzas. The families had a bitter rivalry similar to a south-of-the-border Hatfield and McCoy relationship. During his life, Cuervo established a shaky alliance with the Sauzas, but it erupted into bloody conflict again following his death.

The first José Cuervo

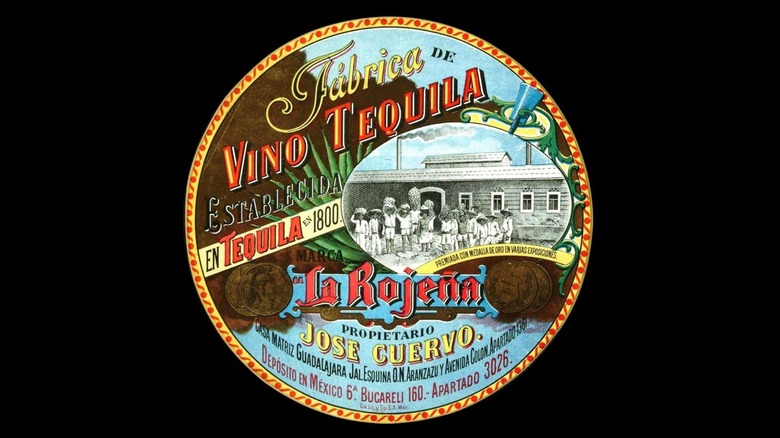

The Cuervo story begins in 1758, when Spanish King Ferdinand VI gave formal land ownership near Tequila, Mexico, to Don José Antonio de Cuervo y Valdés. Nearly 20 years before the U.S. declared independence from England and more than 60 years before Mexico gained independence from Spain, Don José planted the first crops of a tequila empire. Over the next 50 years, José Antonio and his sons continued to expand the empire.

Eventually, the fortune was inherited by his granddaughter and her husband, Vicente Albino Rojas, who founded a distillery in 1812 named La Rojeña, the crown jewel of an emerging industry. The distillery improbably survived years of war and violence, even as many surrounding structures were ravaged and burned. It still stands today as Latin America's oldest surviving distillery.

The wealthy Cuervo family was politically influential. José Cuervo's uncle, Florentino Cuervo, served as a military commander with a ruthless reputation. Despite playing a pivotal role in Porfirio Díaz's ascension to power, Florentino grew dissatisfied with Díaz and was plotting to support another candidate. Florentino died before the plan came to fruition, however, and left the family in a dangerous standing with the ruling dictator.

The second José Cuervo

José Cuervo Labastida was born more than 100 years after his family planted the initial agave crops, but he did not directly inherit the business. While he enjoyed an aristocratic upbringing that included graduating from the military academy, finishing school, and mingling with socialites at cotillions and formal dinners, his father's business was struggling, and debts were mounting. While the Cuervo family struggled, Cenobio Sauza became the dominant producer of tequila at the time. Cuervo and his brothers were unable to overcome their father's debts, and the family holdings were sold at auction following their parents' deaths. Adding insult to injury, the lands were bought by Cenobio Sauza, who continued to add to his tequila empire.

While Cuervo's branch of the family struggled, his great-uncle, Jesús Flores, had a thriving business. He owned multiple distilleries, including La Rojeña, and offered Cuervo a job managing a small one on the edge of town. Cuervo caught a fortunate break when his great-uncle made an unannounced visit. Flores and his wife were on a trip back from Guadalajara and decided to stop due to the risk of encountering bandits in the area. José Cuervo promptly had a room prepared for the unexpected guests and provided a tour of the facility. His uncle was so impressed by Cuervo's work that Flores later asked him to manage La Rojeña when he became too ill to do so himself.

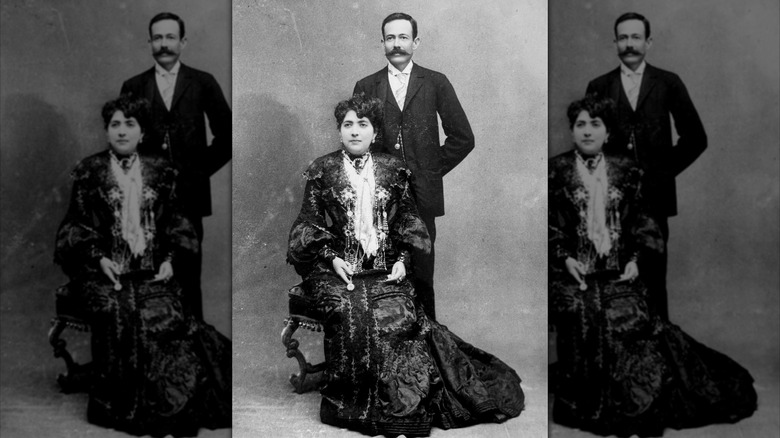

Ana González Rubio's legacy as the first lady of tequila

Ana González Rubio was the second wife of Jesús Flores and was 30 years younger than her husband. Before his death, Flores counseled his wife that his nephew should lead the business into the future. In Ted Genoways' book, he wrote that following the death of her husband, Rubio summoned Cuervo to her mansion in Guadalajara and declared, "I believe it is best for us to marry." Cuervo was hesitant and returned to Tequila to consider the proposal. After weeks had passed with no reply, she invited him back to Guadalajara. "Because of your work obligations, you haven't had time to consider my offer, so I have considered it for us," Rubio said to Cuervo. The justice of the peace entered the room, and they were married on the spot.

They remained married until Cuervo died in 1921, when control of the company reverted to Ana. She helmed the company until she died in 1934, overseeing a prosperous chapter that followed the Mexican Revolution. "She not only succeeded in defending her business and properties but led the entrance of Cuervo, as a brand, into the United States after Prohibition," Genoways said in an interview with The Takeout. Following her death, the company passed to her niece, Lupe, whom she and José Cuervo had raised. Despite their immense contributions, memories of the women faded with time. "They are almost completely forgotten now," Genoways said, "though I hope the book will change that!"

José Cuervo electrifies at the 1904 World's Fair

The 1904 World's Fair in St. Louis was the largest and most expensive in the nation's history. A major draw was the Palace of Electricity. Exterior lights illuminated the 1,500 temporary buildings on the fairgrounds. The electricity not only powered the lights and Ferris wheel, but was also used to astonish visitors with demonstrations of new technology such as the wall outlet, electric typewriter, and X-ray machines.

Technical marvels were a major draw at the fair, but a culinary awakening was also taking place. The hordes of visitors allowed regional dishes to reach mainstream audiences, and the fair is credited with popularizing the ice cream cone, hot dog, cotton candy, Jell-O, and Dr Pepper (which contained some unusual ingredients at the time). José Cuervo was in the thick of it all, showcasing his tequila to an American audience.

The fair was more than just an opportunity for Cuervo to hawk hooch. He was taking in the sights and sounds of the exhibits around him. It reinforced to him that the tequila industry needed to modernize, or risk being left behind. He now understood that getting a train to Tequila was more than a way to transport products. Electric lines could provide the power needed to modernize production facilities. He returned from the fair with a stronger conviction than ever to bring the train to Tequila.

The train to Tequila

Today, there is a train that shuttles tourists from Guadalajara to Tequila while serving tastings and cocktails. Securing the line was a decades-long struggle complicated by natural disasters, shifting political alliances, and American influence. "The tracks that the José Cuervo Express runs on today are the very tracks that José Cuervo, the man, spent years negotiating to have built," Ted Genoways explained in an interview with The Takeout. "I can't help thinking that Cuervo would be delighted to know that the train he fought so hard to build still runs to the town of Tequila, carrying loads of tequila aficionados who are journeying to visit his hometown and distillery."

In 1888, the governor of Guadalajara hosted an opulent banquet that included an indoor garden with flowers from around the world to celebrate the arrival of the train. He boasted about throwing a larger party when the tracks reached the western Mexican coast before the end of his term. A month later, a devastating flood wiped out more than 100 miles of track, creating a humanitarian and economic crisis that resulted in construction delays. It took 21 more years, with Mexico on the brink of revolution, before José Cuervo finally connected the railway to Tequila. He celebrated with mariachis, hat dancers, and a festive outdoor party.

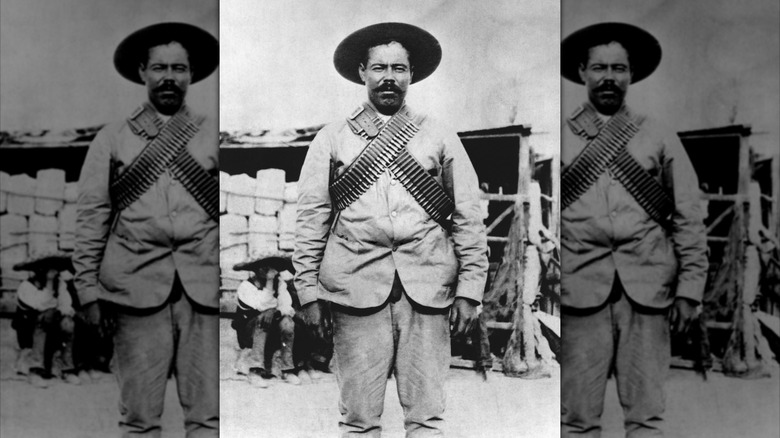

Pancho Villa chases Cuervo into hiding

Ted Genoways' book opens with the cinematic scene of José Cuervo on a ridge overlooking his hometown. He's been riding for hours, fleeing from his mansion in Guadalajara as Pancho Villa's rebel army closes in on the city. He uncorks a bottle of tequila with his teeth, then swigs enough to spray some into the horse's nostrils, numbing its hooves in preparation for the steep descent into a safe refuge. Mexico was in the throes of revolution, a series of conflicts that raged from 1910 to 1920 and was distinguished by shifting allegiances.

José Cuervo wasn't immune to the changing situation. When he built a grandstand in the central plaza of Tequila, it was a public works projects in support of President Porfirio Díaz. He also paved the streets with obsidian stones, brought running water to the main houses, and funded schools. But less than two years after the grandstand was built with Díaz's campaign funds, it was used by one of Cuervo's allies to call for revolution against the dictator.

The initial uprising was led by Francisco Madero. When it was clear that Díaz was defeated, Genoways detailed that the longtime ruler announced he was resigning and seeking exile in France. "Madero has unleashed a tiger," Díaz lamented. "Let us see if he can control it." The Madero presidency was short-lived, and followed by years of war. During this turmoil Cuervo demonstrated what Genoways called maybe his greatest gift, his willingness to disappear.

The suspicious circumstances of José Cuervo's death

José Cuervo emerged from hiding as the war subsided. The tequila industry was in shambles, but there was a unique opportunity to save it. Prohibition had already been enacted in America, with a one-year grace period for implementation. Due to bizarre legislative calendars, a one-month loophole appeared between the expiration of wartime prohibition and the enforcement of the new national ban. Any tequila delivered to the border would find eager consumers paying premium prices.

However, the industry was also facing increased taxation from the Mexican federal government, and Cuervo feared an industrywide collapse would weaken his negotiating position. He proposed a one-year cooperation among the tequila makers. He would transport the tequila on his train, as long as the other distilleries agreed to a price-fixing agreement. Cuervo managed to broker a brief alliance with his old rivals, but as the agreement neared an end, old fractures with the Sauzas reappeared. The Cuervos family looked to political power to swing the pendulum in their favor.

Cuervo's brother was elected to Congress, and Cuervo traveled to Mexico City to counsel his brother to exercise more caution. They dined together, and then both men became ill. José Cuervo never recovered. The official cause of death was pneumonia, but it was rumored that he had been inadvertently poisoned in the attempted assassination of his brother. If true, Genoways wrote, "it would be a bitter irony to end his life."

The aftermath

After José Cuervo's death, control of the company reverted to his wife, Ana. American Prohibition had an interesting impact on tequila sales. The lack of commercial distilleries led to a flood of dangerous homemade liquors on the market, whether or not the American government was intentionally poisoning alcohol. Mexican produced tequila was a safer option. In "Tequila Wars," Genoways referenced a report from the International News Service in Mexico City that stated due to foreign demand, tequila was "a pillar of the financial structure of the nation." Following the repeal of Prohibition, Ana led the formal introduction of the brand into the U.S. market, realizing a lifelong goal of her late husband, José Cuervo.

Despite the business' success, the absence of José Cuervo's calming influence on volatile situations became immediately evident. Cuervo preferred alliance building, and strategic retreats, over violence. But following his death, his brother, Malaquías Cuervo Jr., instigated open warfare with competing tequila families that culminated in a shootout on the cobblestone streets in front of La Rojeña. There were conflicting accounts of what happened, but three members of opposing families were left dead. Then, in the ensuing police activity a Cuervo was killed. Malaquías Cuervo Jr. was arrested for murder, but despite evidence of what Genoways called "obvious corruption," he was absolved of all charges. Tensions between the families escalated into years of conflict.

The legacy of José Cuervo

In "Tequila Wars," Genoways mused that perhaps the best epitaph for José Cuervo is that his name is inscribed on millions of bottles, but the facts of his life remain shrouded in mystery, reminiscent of the way he would strategically disappear in life. "The industry that he built now accounts for a billion dollars in exports each year," he wrote, "and 20 percent of that market still belongs to his heirs."

Ana González Rubio ran the company until her death in 1934. Then control of the company passed to Lupe Gallardo until her death in 1964. "Lupe led the company during World War II and after," Genoways told The Takeout, "and, in the 1950s, introduced the brand Gran Centenario, which honored a hundred years of tequila making by the Gallardo family."

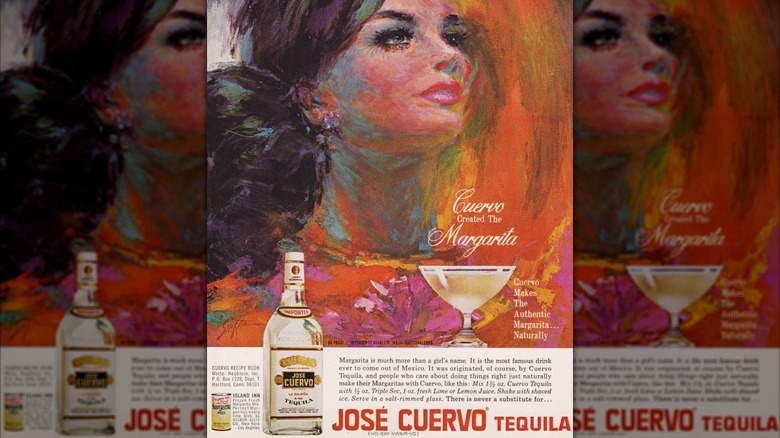

Some of tequila's U.S. success is due to a pair of popular cocktails that brought the spirit to a mainstream audience. While the origins of the margarita are hazy, there is no denying its popularity north of the border. The Rolling Stones also played a role in popularizing the spirit. The Tequila Sunrise was reinvented as a libation for Mick Jagger by a bartender at The Trident, in Sausalito. Not long after, the Stones embarked on one of the most infamous tours — dubbed the cocaine and tequila sunrise tour. As wild as that 1972 tour got, it pales in comparison to the true story of José Cuervo.