15 Types Of Pastry And What Makes Them Unique

Pastries are certainly the creme de la creme of the dessert world mainly due to embellishments like glazes, whipped cream fillings, and the joyfully anticipated butteriness of the first bite. But without pastry itself, there wouldn't be a world of pastry to worship.

It's all deceptively simple. According to Britannica, pastry is made from flour, salt, a large portion of fat, and a small amount of liquid, as well as sugar or other flavorings. But pastry isn't really as simple as its few exacting ingredients. However, different flours, fats, ratios, and mixing techniques can change the entire outcome, making the same four basic ingredients capable of almost anything. Some pastry is rolled and layered while others are stretched. Some are studded with pieces of cold fat. Others are piped onto a baking sheet. Some doughs allow for re-rolling scraps, while others strictly prohibit the dismantling of layers.

The truth is, pastry is thrilling. Approaching a patisserie case full of edible architecture or praying that a homemade frangipane tart won't present that dreaded soggy bottom keeps us on our toes. So, as we pursue visionary layering and golden brown flakes — an appeal that threatens the idolized smell of bacon in the morning — let us appreciate all the work, technique, and precision that allows us to pursue edible greatness. These are some of the more common types of pastry and what makes each one unique.

Pâte a choux

Choux pastry is a landmark dough behind some of France's most prized pastry delicacies. Perhaps the most recognizable are craquelin-topped cream puffs, linear eclaires, and profiterole trios with shiny chocolate ganache cascading down baked choux domes. Choux pastry, however, is far from the average pie crust or tart shell pastry.

Choux pastry is particularly unique because the consistency aligns it more with cake batter than traditional rolled pastry dough. Per Insider, choux pastry dates to 16th-century France and is named for the similarly jagged-looking cabbage. To make it, water and butter are first brought to a boil (via Britannica). After flour and salt are added to form a stiff paste, whole eggs are incorporated until the mixture is smooth and thick. The dough is then piped and baked in the oven until crisp, golden brown, and suitably hollow — a fundamental characteristic just perfect for fillings. This pastry can go sweet or savory, per CIA Foodies. For instance, crowns of Paris-Brest are an oft-adored sweet choux endeavor, while gougères use cheese in the light and airy dough.

As easy as it sounds, choux pastry is actually quite hard to master. Too many eggs will result in a runny batter, too little will make it overly stiff, and bakers must be careful to prevent pastry collapse. The pursuit, however, is well the effort.

Flaky pie pastry

Time stands still when a warm fruit pie hits the table. The first slice is always the messiest — layers of buttery crust collapsing onto juicy apples — and somehow, everyone clamors for the inaugural piece. But steamy baked apple pie interiors aren't possible without a buttery, flaky pie crust.

Flour-dusted countertops and rolling pins are early indicators for pie crust construction, while a cold refrigerator and fast-working hands are key to successfully flaky and tender pastry. But what makes pie crust different from other pastry shells? According to MasterClass, a traditional American pie crust is both flaky and firm, made with flour, a solidified fat, cold water, salt, and sometimes a touch of vinegar or vodka. The fat (usually cold, unsalted butter) is cut into the flour mixture until it's broken down to the size of peas. If it's then kept relatively whole within the dough, the butter melts during baking, creating steam, which them forms those flaky layers. Unlike tart shells, which are designed to be removed from a pan, pie slices are typically served straight from the cooking dish.

Flaky pie crust also allows for some serious creativity. Although you must work fast to prevent the butter chunks from melting, flaky pie dough is very malleable. Pie aficionado Erin Jeanne McDowell shows off one fancy rope crimping method on Instagram. Other techniques include cute cut-out hearts (via Instagram) and classic lattice toppings (via Instagram).

Puff pastry

Puff pastry is nothing short of gluten-based sorcery, seeing as it's crafted to produce thin layers of butter-laced dough through a multistep rolling process. It's all pretty laborious, to say the least. Savory tarts with expansive puff pastry edges, fruit turnovers, and even palmier cookies rely on hours — if not days — of rolling, folding, turning, and chilling (via The Washington Post). The dozens of butter layers created by rolling and folding create steam when the raw dough is introduced into a hot oven, causing it to puff up into all those delicate layers. The result? Delicious pastry flakes that admittedly tend to shatter all over your plate and shirt.

So, what makes puff pastry unique, and why use it instead of any other pastry delicacy? Well, puff pastry is one-of-a-kind due to its lightness and flaky texture. Unlike pie dough, which is firmer and more crumbly, the butter layers of puff pastry spell a dramatic rise that then creates unparalleled height. Making puff pastry at home is a labor of love that doesn't always live up to one's dreams (hello, leaking butter). So, as The Washington Post notes, buying an all-butter puff pastry at the supermarket is a fully approved shortcut.

Yeasted puff pastry

Believe it or not, the truth is that not all puff pastry is created equal. Classic puff pastry has downright magical rising properties thanks to those steaming butter layers. Yeasted puff pastry, on the other hand, combines that buttery steam lift with an additional yeast boost. The smell of freshly baked viennoiserie is both buttery and yeasty, too.

Per Food52, yeasted puff pastry starts with an enriched yeast dough before a baking forms delicate layers of butter and pastry. The combination results in a beautifully light and pleasantly chewy texture with golden brown flakes for days. French pastries, specifically viennoiserie, rely on yeasted puff pastry to achieve structurally sound and buttery croissants, Danishes, and kouign-amann.

So, why bother giving yeast dough a labor-intensive lamination treatment? According to Le Cordon Bleu, viennoiserie bridges the gap between traditional patisserie and more hearty bread. Together, the strong yeast dough and buttery lamination creates pastries with a uniquely quick rise and exceptional flake. Ultimately, the laborious process is rewarded with enchantingly webbed interiors.

Rough puff pastry

As it happens, there is a proven shortcut for the arduous puff or yeasted puff pastry process. Rough puff says it all in the name. It's essentially a "rough" version of full-fledged puff pastry that utilizes folding without the time-consuming step of laminating it all with a central block of butter. Per Anson Mills, rough puff pastry infiltrated modern home kitchens thanks to "The Great British Bake Off" fandom. This approachable puff recipe touts similar height, flake, and flavor to the more traditional methods, with a less serious time commitment. European butter's higher fat and lower water content is best for the most tasty and flaky results. Many recipes call for freezing and chilling the butter before starting the folding process.

Because rough puff yields similar results to classic puff pastry, its true uniqueness lies in the simplified baking procedure. It does take some effort and the occasional bit of troubleshooting, however. If you're making it at home, for instance, and the dough appears dry at first, avoid the temptation to alter the recipe. Too much water will result in a tough final product, so it's better to keep working a bit and allow the pastry to fully hydrate.

Pâte sucrée

Pâte sucrée falls under the shortcrust pastry umbrella. According to The Butter Block, shortcrust pastry requires cold butter to coat the flour, in order to prevent water from overdeveloping gluten and producing an unpleasantly tough pastry. The result skips flaky layers and instead produces a crumbly "short" texture. A traditional French pastry dough, per MasterClass, pâte sucrée utilizes the creaming method to blend granulated sugar, butter, and egg before pastry chefs add in the flour. Although traditionalists make it all by hand, modern-day technology — like a food processor — can step in to simplify the process.

The rich, pale yellow dough is a typical base for bakery window classics like tarte au citron, tarte framboise, or tarte du pommes. The dough is best kept cold (so the butter doesn't soften) and requires a blind bake in the tart pan before you add fillings like fresh berries or cream. To prevent the pastry from puffing up in the oven, you can line the molded pastry with parchment paper and weigh it down with pie weights or dried beans for at least half the baking time.

Pâte sablée

Next on our shortcrust journey is pâte sablée, a close cousin to pâte sucrée, though it utilizes slightly different ingredients. Pâte sablée is also very delicate and resembles the texture of melt-in-the-mouth shortbread, per MasterClass. Instead of granulated sugar, however, powdered sugar is creamed with room-temperature butter and eggs to make pâte sablée. Flour and salt are then added to the mix to complete the dough. The sweet pastry resembles sugar cookie dough, making it primed for additional flavors like vanilla, citrus, and herbs. Pâte sablée can be trickier to work with in hot weather due to its high butter content, occasional almond flour additions, and a melty-smooth powdered sugar texture.

Just like pâte sucrée, pâte sablée is a classic French tart pastry shell base, only slightly more delicate and crumbly. Its cookie dough-like qualities also allow for cookie-cutter fun, so long as the cut-outs are handled gently to keep them intact.

Pâte brisée

Although it sounds basic indeed, pâte brisée is perhaps the most dazzling of the traditional French pastry doughs. Per PJP Online, pâte brisée contains only flour, butter, salt, and cold water. The ingredients parallel American flaky pie dough, but the technique used to combine them is completely different. Instead of rubbing cold butter chunks into the flour, this traditional French method utilizes a stand mixer or food processor to mix the cold butter into the dry ingredients.

The relatively unsweet pâte brisée is best suited for savory fillings, including custardy quiche, Alsatian tarte à l'oignon (via TasteAtlas), and dynamic pissaladiere tarts. With an egg yolk addition (which technically transforms the pastry into pâte à foncer), the final baked texture is the finest and crumbliest of all the French pâte doughs. When it's finally time to slice, the crust will give way instantly to a sharp pairing knife, revealing an unparalleled sandy texture that lingers on the tongue.

Suet pastry

Suet isn't a common baking ingredient on the American side of the pond. However, fans of "The Great British Bake Off" may recall mentions of suet pudding and the fallout that ensued after the 2020 pudding week technical challenge (via HuffPost). But suet serves an important pastry purpose.

According to MasterClass, suet is a type of animal fat that comes from the kidney region of cows and sheep. It helps to create a light and spongy texture perfect for pie crust, dumplings, and other pastries. Suet also has a very high melt and smoke point, making it ideal for higher-temperature environments and applications (via U.S. Wellness Meats). Because the fat stays solid at room temperature, the final dish is less greasy than butter crusts.

Want to try it for yourself? Consider making steak and kidney pie, which is a British classic that relies on a tender suet pastry crust. If you can't find suet at the grocery store, simply swap in frozen butter, lard, or vegetable shortening.

Phyllo dough

Phyllo is simply one of the most exciting pastry doughs on the planet. There's just something about the paper-thin sheets, buttered layering, and baked golden-brown flake-age that excites the tastebuds and makes you have a camera at the ready. Phyllo is a fragile and very thin pastry dough made from flour, water, salt, and oil (via The Washington Post). Without leaveners like baking powder or yeast, phyllo doesn't rise in a traditional sense. Instead, the butter inside helps to create flaky layers.

Per "The Oxford Companion to Food," working with phyllo dough to create baklava, borek, and spanakopita requires careful layering, alternating phyllo sheets with layers of melted butter. Nowadays, phyllo is adored outside its Mediterranean home. Apple strudel, filled phyllo dough purses, and cocktail party tartlets all explore the pastry's versatility and propensity for hearty, flavor-packed fillings (via The Washington Post).

If this sounds intimidating, supermarket phyllo is a good swap for those who aren't up to the challenge of making this famously finicky dough from scratch. Just make sure to thaw the frozen dough in the refrigerator to prevent the sheets from sticking together.

Chinese puff pastry

Delicate, flaky, and custardy egg tarts are a delight, with absurdly flaky pastry dough wrapped around a just-set golden yellow custard. If you're lucky, the tarts are still warm from the oven, and the custard collapses under the roof of your mouth straight away.

However essential the custard may be, the crust is nothing short of revolutionary. Chinese puff pastry, made with lard, originated in Guangzhou, China in the 1920s (via The Washington Post). Unlike western puff pastry, Chinese puff pastry requires two flour doughs, one laden with lard (or butter) and a small amount of flour. The other is a mix of flour, water, and egg. The egg dough is rolled out, the butter dough is placed in the middle, and the two are then laminated together.

Unlike western puff pastry, Chinese puff pastry is far more delicate and lacks any chew at all. The egg introduces a short quality that causes the pastry to flake into a million buttery leaves. It's the only way to properly end a dim sum meal.

Strudel pastry

Although you can snag boxes of store-bought phyllo dough to use when you're in a strudel pinch, we must admit that traditional strudel pastry is in a league of its own. Like phyllo dough, strudel pastry is thin, layered, and becomes wonderfully crisp upon baking (via The Guardian). Phyllo will work fine here, but the truth is that there's nothing quite like a traditional strudel dough when you're looking for an authentically delicious experience.

Proper strudel pastry is easy to gauge when made at home, according to food writer for The Guardian, Felicity Cloake. Cloake's at-home test run outline two differences between phyllo and strudel pastry. First, strudel pastry is soft and elastic, unlike phyllo's more brittle texture. What's more, the final strudel product is unique, with an outer shell of crisp butter-soaked pastry and an inner dumpling-like mouthfeel that happen when the pastry soaks up fruity juices from the filling.

Scorza

Italian cannoli cream gets a lot of love, and for good reason. But without the crisp, tubular shell that surrounds the filling, cannoli would fall well short of its textural appeal. So if you haven't pondered the iconic Italian shells — primed with a fried golden brown color and crisp bubbles — then now is the time.

Per Streaty, scorza pastry is one of three critical cannoli components. Translating to "crust" or "peel," scorza is a dough designed specifically for cannoli, which hails from Sicily. The dough is made from flour, marsala wine, vinegar, sugar, and lard (or butter). It's mixed until it becomes smooth and tacky and is then rolled into very thin circles.

Next, the dough rounds are wrapped around a metal cannoli tube, overlapping like a bow, and sealed together before it's all fried (via La Gazzetta Italiana). The resulting pastry is wonderfully flaky and rich without being overly greasy. A cannolo application does, however, require on-the-spot filling. Otherwise, the delicate fried scorza pastry will turn soggy as it sits, so this is a treat that's best enjoyed as fresh as possible.

Hot water crust pastry

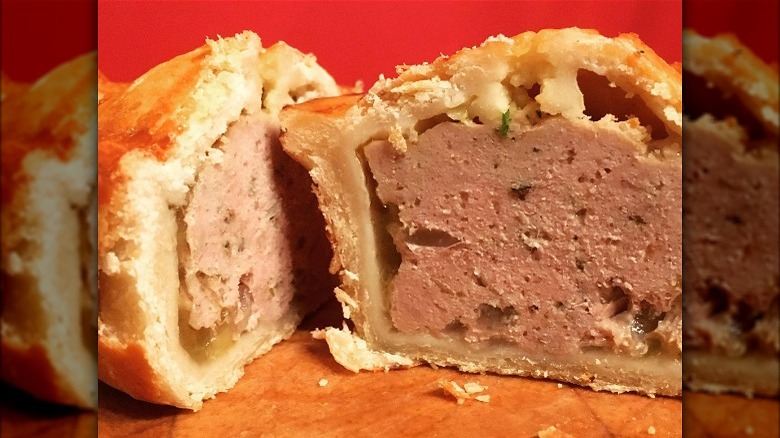

At face value, hot water crust pastry may seem like an oxymoron. The word "hot" is rarely used to describe pie dough, at least in American English vocabulary. After all, baking experts have done their very best to impress upon home bakers that cold butter is the only butter for pie crust. Hot water crust pastry, however, turns pie precedent on its head.

Unlike a traditional flaky pie crust, hot water crust pastry ditches that strategy and instead mixes melted fat with the dry ingredients, creating an exceptionally sturdy dough. It's especially well-suited for juicy meat fillings or creating free-form shapes (via Food52). Not only is the dough made with hot butter and water, but to mold it properly, it must remain warm throughout the shaping process. After the hot water crust exits the oven, you should be enjoying crisp and crumbly golden bits with no sign of toughness at all.

Kataifi

If you've ever walked into a Greek or Middle Eastern bakery, you've surely seen trays of syrup-soaked phyllo pastries of all kinds. Some come with nearly pulverized bright green pistachios, others are rolled up with buttery ground walnuts, and some look particularly bristly. Believe it or not, shredded phyllo dough has a name of its own: kataifi.

According to Greek Boston, kataifi is a shredded pastry dough with a unique baked texture that's almost like shredded wheat cereal, but way better. It also has a feathery light structure. While it likely originated in Turkey, Greece adopted kataifi as if it was its own, using the unique pastry in both sweet and savory applications. A classic dish using the pastry, also called kataifi, is similar to nutty, syrup-soaked baklava. Kataifi shrimp, meanwhile, utilizes the shredded pastry strands as a blanket, wrapping it around fresh shrimp before the whole package is fried.