Suze: The Golden Liqueur That's Made From A Unique Plant

If you've ever been to a fancy bar and seen a tall, slender bottle of bright yellow liquid on the shelves, it may very well have been Suze, the bitter French aperitif that is enjoying a resurgence in popularity. Created in the late 19th century and beloved by bartenders around the world for its powerful flavor and versatility, it isn't nearly as common as similar liqueurs like Campari and Aperol, but if you enjoy complex, aromatic cocktails, it should be at the top of your list of new drinks to try.

Suze is categorized as an aperitif, an alcoholic beverage served before dinner as an appetite stimulant. The category includes everything from dry white wine to sherry, and encompasses bitter liqueurs like Campari, Cynar, and Suze. There are no strict rules about when these drinks must be consumed even though they are traditionally served before dinner. Vermouth, for example, is a type of aperitif that is found in a wide range of cocktails such as martinis and Manhattans, that can be enjoyed at any time of day. Suze brings its own flair to the table. From its bright color to its disputed history to its intricate flavor and uses, we've rounded up everything you need to know about this singular beverage.

It was created in the 1880s

Suze was created by Fernand Moureaux, the heir to a French distillery. Moureaux wanted to create an aperitif that was based on a wild, Alpine plant known for its bitterness rather than on wine, the way sherry and vermouth were. He came up with Suze, a drink named after his step-sister, Suzanne. Although the concept for the drink was unusual, it rocketed to fame in 1889 when it won a gold medal at the Paris World's Fair, the event that also saw the grand unveiling of the Eiffel Tower.

That is one side of the story. The other contends that Suze was created over the Alps in Switzerland by a small-town herbalist named Hans Kappeler. Through Kappeler's village ran the Suze River, adding credence to this version of events. Recognizing a good recipe when he saw one, Moreaux purchased it from Kappeler and began making it on a large scale. To this day, however, the manufacturer's website favors Moureaux's side of the origin story and omits any mention of Kappeler.

Whoever invented Suze, Moreaux turned it into a big business, releasing the signature bottle and label in 1912. The drink became popular in Paris, where it gained pride of place behind the bar during the latter years of the Belle Époque.

It's made from wild gentian root

The ingredient that gives Suze its distinctive bitter flavor is gentian root, the below-ground part of the gentian plant, which produces deep purple or yellow flowers on Alpine mountainsides. Before it was used in liqueurs, it was used for medicinal purposes. All the way back in Ancient Greece, doctors were prescribing it for its supposed ability to cure digestive issues. A bitter, medicinal root might sound like an unconventional ingredient for an alcoholic beverage, but gentian is also a key component in other aperitifs, including Campari, Aperol, and many types of vermouth. Most cocktail bitters also benefit from its powers, including the ubiquitous Angostura Bitters. Aside from its bitterness, fresh gentian root provides an earthy flavor that stands out more prominently in Suze than in other drinks due to its high concentration.

The gentian roots that are used for making Suze are harvested by hand after they have been allowed to grow for at least 20 years, though some farmers allow them to grow for closer to 40 years. Luckily, a little goes a long way. It only takes about five pounds to make 50 bottles of the brightly colored liqueur.

The roots are macerated for over a year

It takes gentian roots at least 20 years to reach the level of maturity required to make Suze, but the process remains slow and deliberate even after they've been harvested. Once they are washed, the roots are turned into strips called "cossettes" that are then soaked in neutral alcohol for over a year. Afterward, they are pressed to extract every ounce of flavor. The liquid is then distilled in an alembic still to produce a lightly golden-hued substance that is 70% alcohol and packed with earthy gentian flavor.

On its own, this bitter, intensely alcoholic beverage would be on par with the most throat-searing liquors on the market. To make Suze an aperitif, other ingredients must be added to dilute the alcohol and inject more complexity into the flavor profile. The precise recipe for Suze is proprietary and a closely held secret. However, according to the company, it includes an assortment of fruits and plants. Given the liqueur's distinctive, aromatic bouquet, it's clear that there is a strong emphasis on the herbal ingredients.

It has a complex flavor profile

Like all aperitifs, Suze is meant to be enjoyable on its own terms. It isn't like vodka that you either mix into a cocktail or down in a single shot, nor is it like wine or beer that you can leisurely drink throughout the evening. It falls somewhere in between, with a lower alcohol content and punchy flavor. We may never know its precise ingredients in Suze, but they combine to make a heady, aromatic beverage that falls between the bitterness of Campari and the sweetness of Aperol.

After the first impression of bitterness and sweetness, Suze provides a wave of other flavors, including herbal, floral, spiced, and slightly woody notes. According to the brand, it also contains vegetal undertones, with a pronounced flavor of citrus and candied fruits. This lengthy list of contrasting flavors somehow blends into a seamlessly smooth, aromatic drink that perfectly balances bitterness and sweetness and allows the botanicals to be seductively complex and harmonious.

It has a mid-range alcohol content

Aperitifs are not meant to be heavily alcoholic. Their purpose is to stimulate the appetite, not conceal it with a wave of tipsiness, so you probably won't feel their effects after only a few sips. For pre-dinner drinks, you want something light, with a punchy flavor and easy drinkability. To further ensure that they are not suppressing the appetite, aperitifs are often mixed with carbonated beverages to further dilute their alcohol content (think of a classic Aperol Spritz).

Suze has a high to mid-range level of alcohol compared to other liqueurs in its category. Where Aperol is 11% alcohol and Cynar, a popular artichoke-based aperitif, is 16.5%, Suze is 20%. Meanwhile, on the far end, Campari is 24%. To complicate matters, customers in Europe will likely be drinking a lighter version of Suze. While the bottles sold in America are usually 20% alcohol, many of the bottles sold in Europe are only 15%.

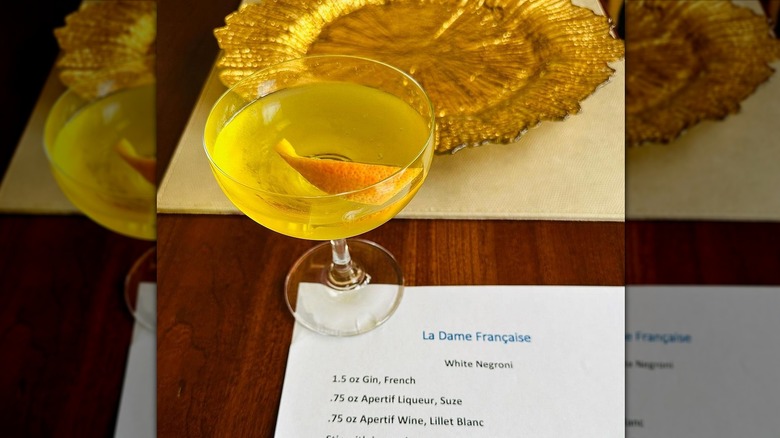

It's versatile in cocktails

Although aperitifs are often served with nothing but ice or carbonated water, Suze is a bartender's secret weapon. Its vibrant color creates a striking visual element to cocktails, but it's the flavor that makes it the darling of cocktail connoisseurs. You can use it to make a light, bubbly aperitif or a bold, layered drink that is better suited to swanky cocktail bars where you can sip it slowly without the distraction of food.

For something light and citrusy, combining it with a dry sparkling wine and a sweet cordial or juice, such as elderflower or pineapple, will provide a bright, citrusy spin on an Aperol Spritz. If you're new to Suze or aren't confident in your mixology skills, you can simply swap it for gin in a classic gin and tonic. The resulting drink will be sweeter and less alcoholic than its inspiration, so you might want to ease back on the tonic and dial up the Suze. You can also use it as an accent in classic, stripped-back drinks like martinis.

Then there are the more adventurous options. Because of its earthy bitterness and range of floral and herbal flavors, Suze can be used to striking effect with other powerful flavors. Many recipes mix it with mezcal, the agave-based liquor with a pungent smoky taste. Its bitterness even helps balance vegetable juices if you like a savory edge to your drinks.

Its bitterness plays a special culinary role

Of the five basic flavors – salty, sweet, sour, bitter, and umami — bitterness is probably the least likely to be named as a favorite. We don't consciously add a dash of bitterness to all our foods the way we do with sugar and salt. In fact, the word has come to mean anyone or anything that is resentful or uncomfortable. And yet, bitterness is an essential ingredient in the world of gastronomy, whether you're making a mouthwatering dessert or a well-balanced cocktail. In the culinary world, popular bitter ingredients include dark chocolate, coffee, Brussels sprouts, arugula, and grapefruit, while in the world of mixology, bitterness is one of the most common features of certain liqueurs, mixers, and aromatics.

Most alcoholic beverages contain some element of bitterness, whether it's the phenols in wine, the woody flavor of barrel-aged spirits, the gentian root in aperitifs like Suze, the quinine in tonic water, or the addition of bitters in craft cocktails. Bitterness is not a pleasant flavor on its own. Scientists believe that humans developed a sensitivity to it in order to detect whether a plant was toxic. However, it is an essential way to balance sweetness. Without a hint of bitterness, cocktails would be too sweet, and without sugar, they would have little flavor aside from straight liquor. Bitterness also heightens our taste, amplifying the other ingredients like a spotlight for your tastebuds.

It contains some unexpected ingredients

Although the precise Suze recipe is a closely guarded secret, the brand is an outlier in the industry in that it publicizes some of its ingredients. If you search for similar information on Campari, Aperol, or pretty much any other alcoholic beverage, you're unlikely to find concrete information from the manufacturer. The details about Suze are revealing, showing that the brand relies on more than just gentian root for flavor and color.

The first three ingredients are, not surprisingly, softened water, alcohol, and sugar, followed by gentian extracts. Rather than listing the precise combination of plants and fruit that provide the drink's signature bouquet, the manufacturer merely refers to "botanical extracts."

One of the surprising ingredients is concentrated apple juice. Apple is rarely referenced when describing the flavor of Suze. However, apple juice has a sweet, subtly fruity flavor that is ideal for a beverage that isn't meant to taste like a particular fruit. It also contains artificial coloring agents E150a (caramel color) and Yellow No. 5 (also known as Tartrazine) to provide its vibrant yellow hue. Tartrazine was cutting edge when Moreaux founded the brand, having been discovered in 1884 by a German chemist. At the time, it was mainly used in textiles and wasn't approved by the Food and Drug Administration for culinary uses until the 1930s. Now it's used in everything from gummy bears to shampoo.

It holds a prized role in French culture

Aperol and Campari are the ubiquitous aperitifs around the world, but in France, Suze holds particular resonance due to its associations with La Belle Époque. The so-called "beautiful era" took place between 1870 and the beginning of World War I in 1914, and marked an explosion in art, literature, architectural experimentation, fashion, and shameless excess. Much of what we now associate with Paris was created during the period, from the Eiffel Tower to the work of Impressionist painters like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Edgar Degas. Suze appeared in the late 1880s, and with its slender, stylish bottle and gaudy yellow hue, it fit right in.

During La Belle Époque, restaurant culture surged. Glittering bars and restaurants spilled into the streets, and while champagne may have been the most emblematic beverage of the era, French-born aperitifs like Suze and Lillet were not far behind. These brands pushed the boundaries of poster design, blanketing Paris in advertisements. Lillet's designs even served as inspiration for fashion mogul Christian Dior. The era may have ended more than a century ago, but there is something deliciously retro and extravagant about drinking Suze, even if you aren't lounging in a bar in Paris.

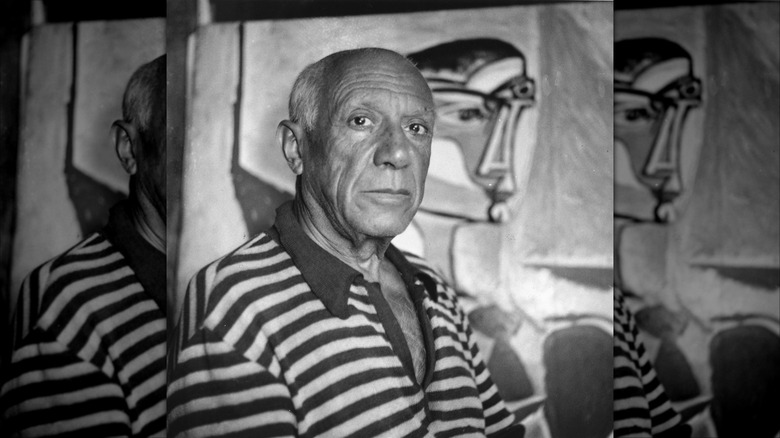

It makes an appearance in a famous work of art

Perhaps the clearest indication that Suze was deeply embedded in the glamorous culture of early 20th century France is its starring role in Pablo Picasso's 1912 painting "La bouteille de Suze" ("Bottle of Suze"). Made with charcoal and paint along with newspaper clippings and patterned wallpaper, it depicts a bottle of Suze, a cigarette, an ashtray, and a glass on a blue oval table. Like most of Picasso's work, the objects are not immediately identifiable, and it is significant that he chose to put the original Suze label on the bottle to leave the viewer in doubt.

As a pioneer of the Cubist movement, Picasso was pushing the form into a new phase with the painting. Where Analytic Cubism had been about breaking apart objects, such as a person or a landscape, into geometric shapes and arranging them on a canvas, Synthetic Cubism brought pieces of magazines, newspapers, and other materials onto the canvas to construct the subject. The isolated scene in Bottle of Suze — a table strewn with a mostly empty bottle of the famous French liqueur and an ashtray and cigarette — points to the period of leisure that the upper classes in France were enjoying at the time, while the newspaper clippings about the Balkan War suggest the cognitive dissonance that was at the heart of the revelry. The painting is now part of the permanent collection at the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum in St. Louis.

It wasn't available in the U.S. until recently

Outside of Europe, Suze struggled to gain a foothold. Despite our obsession with all things French, and the ready availability of everything from croissants to Chanel No. 5, Americans couldn't get their hands on the bright yellow liqueur until 2012 unless they'd traveled home from an overseas vacation with a few bottles tucked away in their luggage. The reason it took Suze so long to find its way to American soil may have had more to do with historical preferences rather than the vicissitudes of international alcohol distribution. Whenever it was referenced in 20th-century American or English publications, the descriptions were rarely flattering.

In the 1950s, American journalist A. J. Liebling referred to the "horrid tasting French drinks like St. Raphaël, Suze and Raspail," during a trip to his old World War II haunts, while English journalist Alex Hamilton called Suze a "foul drink, smelling of vapor rub" in 1985. As these descriptors illustrate, Suze is an acquired taste that did not fit the profile of what American and British drinkers were consuming in the 20th century, leaving little incentive to expand the market. But in the early 2010s, pre-Prohibition era cocktails became all the rage, and bitter liqueurs that had fallen into obscurity like absinthe and fernet became the next big thing. Suze rode this wave all the way across the Atlantic and can now be found in stores and on cocktail menus across the U.S.

The brand has stuck to tradition

In 1912, Suze unveiled the signature bottle and chunky-fonted label design that it maintains to this day. Tall and slender like a narrow bottle of wine, it shows off the drink's bright color, while an inky sketch of a gentian flower behind the logo gives a nod to the plant that started it all. The bottle and its design are just a couple of ways that the brand has kept things traditional after over a century. It also claims to use the exact recipe and production process that it created in the 1880s, all the way from the maceration of the wild gentian to the precise blend of botanicals.

One thing that has changed for the brand, however, is its range of products. Although the original beverage remains the same, the company released a zero-alcohol tonic that is sold in 250-milliliter bottles and boasts the same bright color and bittersweet flavor for those who aren't interested in the alcoholic component. Although it does not appear to be available in the U.S. yet, the brand may expand it stateside eventually.

It's moderately priced for an aperitif

Anyone who's gone for a night out with friends can attest to the fact that alcohol is not cheap. One cocktail might cost as much as an entire entrée, while a moderately priced bottle of wine can leave you wincing at the cash register. Lucky for those who are curious about the world of French aperitifs, Suze will not break the bank. Despite being a relatively obscure beverage compared to, say, Campari or vermouth, it won't set you back much more than prominent products in the aperitif category.

Depending on where you purchase it, a 750-milliliter bottle of Suze will likely cost about $35. This puts it in lock-step with Campari and slightly above comparable aperitifs like Aperol, Lillet, and the artichoke-based Cynar. Meanwhile, a high-end French vermouth could cost you closer to $50, and champagne, which is also considered an aperitif, can be pretty much as expensive as money can buy. If you're curious about craft liqueurs, Suze is a relatively affordable place to start despite its storied history and popularity among bartending aficionados.