The Untold Truth Of TaB

TaB may not be around anymore, but it left an indelible imprint on American society while it was here. As Coke's first-ever attempt at a diet soda, it showed that consumers had an unquenchable thirst for indulgences they could enjoy (supposedly) guilt-free. TaB courted its fair share of controversy over the years, from airing commercials with body-shaming, anti-feminist slogans to changing its formula because of health scares about artificial sweeteners, but it was a supermarket icon in its 1970s and '80s heyday. Its popularity fizzled after that, but you could still see the famous bright pink cans in the hands of TaB diehards who made up for their small numbers by consuming copious amounts of this no-calorie elixir and singing its praises far and wide.

TaB may have tasted more like a tin can than it tasted like Coke, but its story is still filled with many interesting twists and turns, and people mourn its loss to this day. This is the untold truth of TaB.

It was not the first diet soda

TaB was an early innovation in the field of zero-calorie soft drinks, it wasn't the first diet soda on the market. Diet soda was actually invented by a man named Hyman Kirsch in 1952, 11 years before the Coca-Cola company released TaB. His product was called No-Cal, and he intended it as a healthy alternative to soda that diabetics and people with heart issues could drink without fear.

However, quickly after it was released, No-Cal became associated with female dieters rather than diabetics. According to Bay Bottles, a skinny Hollywood actress, Kim Novak, started appearing in ads for the drink. The next two zero-calorie sodas that hit store shelves ended up marketing themselves directly toward female consumers who wanted to shed pounds. Canada Dry called their line of diet sodas Glamor, and Royal Crown Cola put the word "diet" right in their new soft drink's name. Diet-Rite, as it was called, was actually advertised to diabetics at first, and it was even sold in the pharmacy section of grocery stores. However, dieters bought way more of it than diabetics did, so much so that it was one of America's best-selling sodas by 1960, only two years after its release.

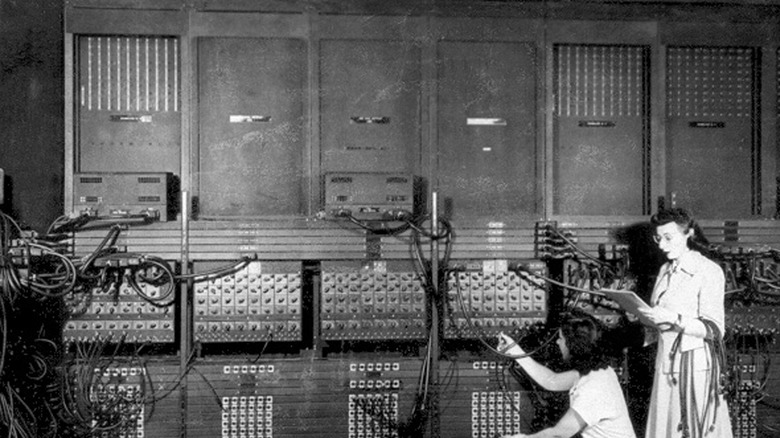

Its name was generated by a computer

Coca-Cola knew it had to keep up with the times and develop its own diet soda. It wanted to create a diet cola that tasted kind of like Coke, but the company decided to avoid calling it Diet Coke. Most people thought diet soda tasted bad, and Coke didn't want to damage its flagship brand with a nasty diet product. According to Snopes, using the Coke name for a diet beverage was even called "heresy" by one Coca-Cola executive. Because of this, the company had to come up with a new name for its experimental diet soda — quickly — as development on "Project Alpha" (the code-name of the new diet drink program) started in 1962, and the product was released in 1963.

Although there's a popular story that claims that the TaB name is an acronym for "Totally Artificial Beverage," it's just a myth. The real origin of the name is just as wacky, however. Snopes notes that Coca-Cola used an early IBM mainframe computer to generate over 2 million random four-letter words. The marketing team selected two dozen of the best contenders for market research. The winner was tabb, which lost its second "b" by the time the drink appeared on store shelves. The name may have resonated with customers as a reference to "keeping a tab" on their bodyweight.

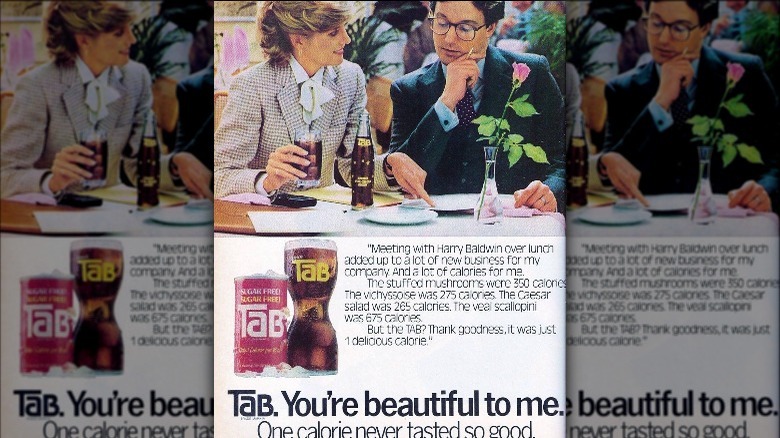

TaB's early advertising could be problematic

When TaB was released, it was marketed directly at people who wanted to lose weight, especially women. The cans were bright pink, and the commercials featured skinny women who fit into mainstream beauty ideals at the time. The brand's now-somewhat-horrifying late 1960s commercial with the tagline "Be a Mindsticker" exhorted women to "keep [their] shape in shape" to please their man, so he would daydream about them wherever he went. Another ad that featured a slender woman in a bikini said that TaB was for "beautiful people" and emphasized its purported weight-loss benefits by showing a straight-sided glass of TaB transform into a glass shaped like a classic hourglass waistline.

Celia Viggio Wexler, writing for NBC News, explains how TaB's marketing helped contribute to America's harmful beauty standards for women. The ads reflected the culture's obsession with thinness at the expense of overall wellbeing. Although TaB debuted at a time when the feminist movement was gaining steam, the brand's commercials showed that many people still thought that women needed to stay skinny for the benefit of men.

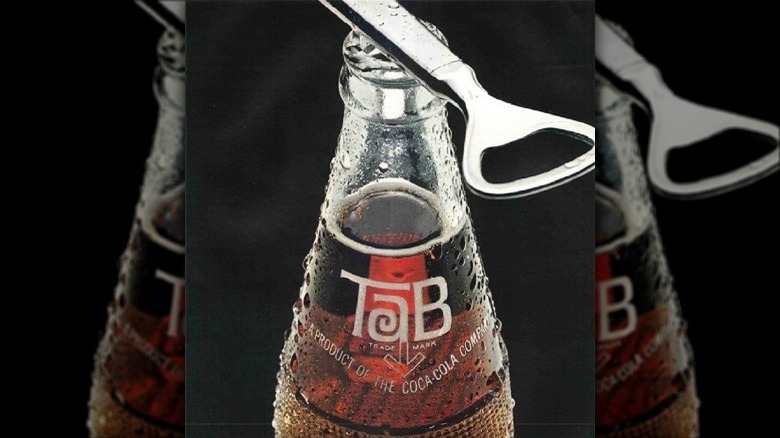

It tasted metallic and bitter

We've talked about the marketing and the name, but what did TaB actually taste like? It was an acquired taste, to say the least. Although it was a cola, according to this Quora post, TaB tasted significantly less sweet than Coke. The poster compares the flavor to cola with a hint of tonic water. More notable than the initial taste was the aftertaste, which was strong and reminiscent of aluminum.

The metallic aftertaste is one of the most common attributes that gets mentioned when people describe TaB, even those who were fans. One TaB enthusiast told The New Yorker that his favorite drink "tastes like metal." According to The New York Times, that distinctively harsh aftertaste could be ascribed to the saccharin in the drink, which had a stronger artificial flavor than aspartame or other artificial sweeteners. While a soda with a bitter, metallic aftertaste certainly doesn't sound pleasant to us, for some, that flavor was key to their enjoyment of the drink.

TaB was a victim of a 'sweetener scare'

Fast Company writes that TaB's original formula was sweetened with cyclamate and saccharin. However, the brand ran into an obstacle when cyclamate was banned by the FDA in 1969. Per The Wall Street Journal, FDA scientists had found that cyclamate and saccharin caused cancer in animals (via I Love TaB). There was a problem with the research, though: the animals in question had been injected with doses of sweetener hundreds of times higher than anyone would ever consume in food. Nevertheless, TaB had to comply with the regulations and remove cyclamate from the drink. Fast Company notes that this had a deleterious effect on TaB's flavor, as the cyclamate masked saccharin's bitterness.

Saccharin itself faced scrutiny, as it, too, was shown to cause cancer in rats when injected in high doses. According to an article in "Current Oncology," research has not demonstrated any connection between saccharin consumption in humans and increased cancer risk. Now, health agencies in the U.S., as well as the World Health Organization and the E.U. Scientific Committee for Food, say that saccharin does not cause harm at normal dietary doses.

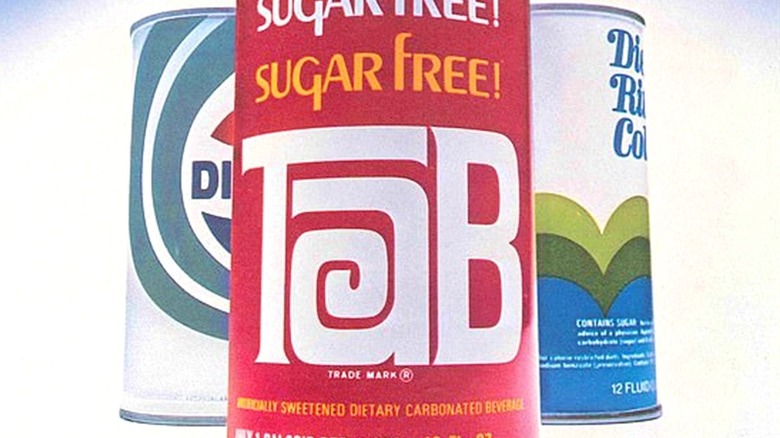

For a time, it was America's favorite diet soda

TaB wasn't exactly an overnight hit. It captured 10% of U.S. diet soda sales in its first year, but then Coca-Cola sabotaged the brand by releasing Fresca, a grapefruit diet soda that overshadowed the struggling TaB (via Fast Company). However, it recovered from the rocky start to become something of a sensation in the 1970s and early '80s.

In the '70s, TaB expanded beyond its cola roots to become a whole line of diet sodas. You could buy TaB in ginger ale, root beer, strawberry, black cherry, orange, and lemon-lime flavors. By 1980, when Coca-Cola began developing Diet Coke, TaB was the world's most popular diet soda. Per The New York Times, it was still America's favorite diet soft drink in 1982, when it captured 4% of the total soda market (including both diet and non-diet drinks). However, its reign at the top would prove short-lived.

Diet Coke turned TaB into a niche product

The seeds of TaB's ultimate demise were sown by its own manufacturer: Coca-Cola. The company began secretly developing Diet Coke in 1980. The brand was a little concerned that introducing Diet Coke would damage TaB's sales, but thought the potential benefits outweighed the risks. Diet cola sales were growing three times as fast as conventional cola sales were, and Diet Coke had an opportunity to become a blockbuster product if it was successful.

It turned out to be the massive hit that the company hoped for. Within one year of its 1982 release, it was already the most popular diet soda in the U.S. With female consumers, it was the number one soda overall. Diet Coke was marketed as a better-tasting alternative to existing diet drinks, a claim which can't help but seem like a dig at its older sibling, TaB.

Its success immediately damaged TaB. Per The New York Times, TaB's share of the soft drink market dropped by 1.5% between 1982 and 1984. The losses would continue. As we've already reported, by 2019, Diet Coke claimed 35% of the diet soda market, while TaB sat at a measly 0.1%. Diet Coke is now the second-most popular soft drink in America (via Newsweek).

New TaB was almost as disastrous as New Coke

Remember New Coke? Per History, Coke, feeling pressure from Pepsi's growing popularity, decided to change its recipe. They did extensive market research, landing on a formula that tested better with consumers in market research studies. The company unveiled New Coke in a splashy press conference in 1985. Within three months, facing consumer outrage at the recipe change, the original formula was brought back under the name Coca-Cola Classic.

New Coke would go down as one of the worst product flops ever, but maybe Coke could have avoided it if they heeded the lessons they learned just a year earlier from TaB. According to The New York Times, Coca-Cola changed the formula of TaB in 1984, switching out the saccharin for aspartame, which has a less pronounced aftertaste. Just like New Coke, this new TaB performed well in taste tests, with testers choosing it two-to-one over the old TaB. However, once it actually hit the market, TaB's loyal fanbase was incensed. They preferred the previous formula's harsh saccharine taste, and several people told the Times that the change had put them off TaB completely.

TaB Clear may have killed Crystal Pepsi

Although Coca-Cola may have kneecapped TaB by releasing Diet Coke, they were still able to use TaB as a weapon against their main competitor: Pepsi. According to Mental Floss, Coke created a transparent version of TaB called TaB Clear, not because they wanted to capitalize on the clear craze of the early 1990s, but because they thought it would sabotage Pepsi's splashy new clear product: Crystal Pepsi.

Pepsi had high hopes for its transparent, fruit-flavored cola. It predicted that Crystal Pepsi would capture 2% of the soft drink market, and spent money on marketing and development accordingly. Coke's chief marketing officer, Sergio Zyman, had other ideas. He thought that if Coke could release a competing product without spending too much money on developing it, the company could tank Crystal Pepsi and prevent Coke's mortal enemy from stealing a chunk of the soda market. Even more deviously, he thought that since TaB Clear was a diet beverage, it would make people think that Crystal Pepsi was also a diet drink, reducing its appeal. We can't be sure if TaB Clear is actually what slew Crystal Pepsi, but Crystal Pepsi did indeed flop, costing Pepsi a bunch of money in the process.

There was briefly a TaB energy drink

As we've seen, Coca-Cola has never been reluctant to mess with TaB's recipe. From switching the sweetener to introducing different flavors to releasing a clear version for trolling purposes, TaB has gone through a variety of transformations over the years. In 2006, the company tried to capitalize on the expanding energy drink market by releasing a TaB-branded energy drink. Per SFGate, TaB Energy didn't have much in common with its namesake soda. It wasn't cola-flavored, but instead had kind of a generic candy taste. According to BevNet, the actual beverage was colored pink as well, not just the can. Instead of saccharin or aspartame, it was sweetened with sucralose (also known as Splenda).

SFGate writes that the one thing TaB Energy shared with TaB soda (other than the pink can) was that it was marketed aggressively toward women, specifically young women in urban areas. The strategy didn't pay off, and BevNet notes that TaB energy has been discontinued.

It had a following among journalists

Although TaB became a somewhat hard-to-find specialty product after Diet Coke was released, it retained a small but loyal consumer base. Actually, loyal undersells the devotion TaB fans had for their favorite soft drink: Their love for TaB was downright fanatical. The New Yorker reported in 2006 that journalists were some of the most fervent members of the TaB appreciation club.

The publication interviewed several TaB enthusiasts who worked in high-powered media jobs at the time, including the owner of The Atlantic, New York Magazine's film critic, the C.E.O. of Air America, and a Columbia Journalism School professor. TaB was not widely available in 2006, so these esteemed individuals had to go to great lengths to acquire it, resorting to having assistants hunt for TaB or buying in bulk from beverage wholesalers. Some of them drank a truly frightening amount of TaB — one drank two cans with breakfast every day, while another went through two cases a week.

Coke discontinued TaB in 2020

Although Coke didn't sell a lot of TaB in the 21st century, it kept hanging on to the brand. Perhaps it was afraid of angering TaB's vocal fan club. However, the beverage just wasn't popular enough to last forever, and the company announced in a press release in 2020 that TaB was finally getting canned (pun intended). Coca-Cola said that ditching TaB, along with some other underperforming brands, would free up resources to promote other beverages with more growth potential.

We reported at the time that discontinuing TaB was a small facet of Coke's strategic response to the pandemic, which involved focusing on core products and simplifying operations. TaB was in good company; over half of the company's products ended up on the chopping block during this time. Even in 2020, TaB retained some power users. The chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, Ajit Pai, tweeted, "We've withstood so many of the difficulties and disruptions that 2020 has thrown our way, but this is a really big blow."

There's a movement to bring TaB back

When any cultural product with a cultish fanbase gets killed, you can bet that consumers will band together to advocate for its resurrection. It happened with the Snyder Cut. Ditto for "One Day At A Time." Now, a group of hardcore TaB enthusiasts is trying to pressure Coca-Cola to bring back their beloved diet cola.

The group calls itself The SaveTaBSoda Committee. According to its website, it began organizing right after TaB officially bit the dust. Now it's a real, registered nonprofit that works to lobby Coke to start making TaB again.

If you feel bereft without the sweet, metallic taste of TaB in your mouth, the Committee lists several ways to help the cause on its website. You can donate, sign a petition, send emails to Coca-Cola employees, or phone Coke directly and harangue some poor call center worker about how TaB's absence is ruining your life. The Committee's efforts have not succeeded yet, but there's always hope: They brought back Crystal Pepsi after all.