Lidia Bastianich Talks Cooking With Her Grandma And Italian Food - Exclusive Interview

Cooking along with Lidia Bastianich feels as familiar and comforting as slipping on your favorite fall jacket. This is not, exactly, the revelation of the century. Bastianich has long had that singular, magical effect on her viewers and cookbook collectors. She's the queen of Italian cuisine, but she might as well be the enchantress. In a Glenda the Good Witch kind of way, she eases into the art of pasta and polenta, like it was what we were all born to do.

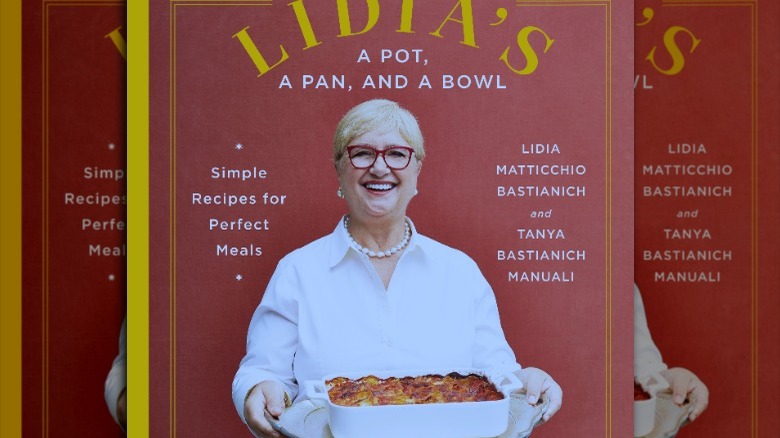

If there were ever proof that Bastianich has a never-ending reservoir of culinary advice to gift us: here it is. She's coming out with another cookbook — i.e. Italian cooking bible — "Lidia's a Pot, a Pan, and a Bowl," set to be released on October 19. In this interview with Mashed, Bastianich gives us exclusive, tantalizing tastes of her cooking journey: from her childhood cooking with her grandmother to her friendship with Julia Child, to her memories of her own grandchildren making gnocchi in her kitchen. She gives us advice, like golden fairytale eggs. You think you know how to follow a recipe? Maybe think again.

"Food is sacred," Bastianich professes to Mashed. "It's nurturing, it's wishing life, giving life." As she says that, everything begins to fall into place.

Lidia Bastianich shares her grandmother's culinary magic

You've talked about how your use of ingredients is rooted in your childhood. Are there any specific dishes or techniques that your grandmother taught you that you carry with you and may have passed down to your own grandchildren?

My food, for me, is identifiable with my grandmother, with the settings. With the setting, actually, where I learned these things from her, in her way — helping her, doing things, working in the garden, feeding the rabbits, skinning the rabbits, cooking the rabbits, making the gnocchi. My flavors, they do represent me: they represent my history, the flavors of who I am. People see themselves in very different ways. I can identify with the flavors, the foods, the aromas, all of that. And so, the question is, "how does this identify me with my grandmother?"

Well, I think there were rules, I guess, dictated by nature — timing, maybe climate, or whatever — that she followed and she respected. That was the seasonality. And we knew exactly what was coming and we were getting ready for what was coming. And [I remember] how she tried to capture these flavors — and we had them impromptu when they were just produced. But also how to save these flavors. We have our freezer now. In those times, life was different. [You had to decide how] to preserve [food], whether you make jams out of it, whether you dry it, whether you ferment it. So all of these, for me, are basics of ... I guess, I see evolution also in today's world through those elements. But somehow, I revert to them a lot because I think that maybe those times and those elements depended much more on nature and reality. And today, we depend a lot on technology and all of it, which is different, which is great, but there is a big difference.

Do you have a favorite dish that you cook with your grandchildren?

Well, they loved gnocchi — making gnocchi — since they were small. Because it's very tactile. And then we played with it. They'd each get a little piece. And then, they would shape it. And of course, they came all different shapes. And then once we cooked it — because I cooked what they made — they would trace ... the ones that they'd made. They're like, "Oh, I made this one." And ultimately, sort of, [it gave them] a sense of accomplishment, a sense of belonging and then feeding others. So gnocchi were one of the elements that, kept the children around the table. [Making it] gave them a good [way to] use their senses — the tactile, especially — and ultimately, enjoying it and sharing.

The flavors of Lidia Bastianich's childhood

When you talk about flavors and aromas that you carry with you that define you, can you name a couple of flavors and aromas that come to mind?

Yes. Rosemary, bay leaves, sage, parsley, fresh parsley, scallions, garlic, all of these are elements that we grew. I mean, rosemary, we had bushes of rosemary. We played as children, hide and seek, in the rosemary bushes. [We] sort of infiltrated the rosemary bushes so that we couldn't be found. But boy, you came out of there and you smelled like rosemary for two or three days. And rosemary, for me, is a very defining smell. For me, right away, roasting comes to mind, potatoes come to mind, chickens come to mind, lamb comes to mind — this kind of roasting element.

Bay leaf is another one. Bay leaf, again, big bushes, [I'm not talking about the] not the dry [leaves], but the fresh [leaves]. I would go out and harvest them and bring them to grandma. But how those bay leaves, I mean, they [released] the aroma. But they ... also... they conserved the food, they protected the food. Because it has some natural antibacterial elements and all that. When we had the pig, they slaughtered the pig. And to cure the meat, salt and bay leaves were the main ingredients, garlic too. And so these flavors take me to a place, a time in a year, in a season, to an event, or booking, or drawing that I did with grandma and that was part of life then.

You talk about cooking as a memory, and also as an act of love and community. Can share some memories that illustrate that?

I remember my grandmother getting up 4:00 or 5:00 in the morning and she was serving the animals. She would go into the yard, she would dig the vegetables, she would water the vegetables. So her functionality, from the moment she got up to the moment she went to bed was: how is she going to produce food to feed her family? How is she going to feed this family? And it's impressive. The woman, she did everything from feeding the animals, you know we would go and collect clovers and feed it to the rabbits. And then, of course, Sunday came, and [we had a] great shuba with the rabbits, with some homemade gnocchi. It's sort of, those circles are always something [that resonated with me]. It was to a better end. Whatever she was doing during the day culminated in feeding the family, in the kitchen with those wonderful aromas.

And you know, what is food? From a mother nursing a baby, it's nurturing. It's wishing life, giving life to ... the baby so that it grows strong, so that it survives. Food is a way of communicating, connecting. Also, you transport yourself — part of you — into this cycle, newly born. I mean, infants recognize their mothers by their smell. Because they don't see right away, but they recognize their mothers by their smell — it's the milk — and that gives them security. So food, for me ... food is sacred. It keeps us alive. I think that if you really research, the wars that have been, the tribal wars, the bigger wars — it was all about having food for your people, your family. It all begins, in the small world, where it's mother and child, and family and children. And then [it extends to] the extended family. It's circles of this intensity of love that is shared with food.

The first two American foods that Lidia Bastianich fell in love with

What were your first experiences with American food or even other immigrant cultures' food when you moved to the U.S. at 12 years old? Is there a dish that particularly impressed you when you first immigrated to the United States?

Well, first for us, being, sort of, an immigrant, [and after] being two years in a refugee camp, finally, it looked like we were going to have a home. This was going to be where I'm going to stay and my roots. I was becoming American, I was getting to know America. So, I remember when we would go in the stores with my mother, you know, food shopping. I couldn't believe the size. I couldn't believe the amount of ingredients. All this packaged ... and whatever. You know, wasn't what I was used to — the fresh food, mounds of all the fresh food, or the open market, or whatever. But in a way, it was more challenging. This is America, we've come to the good times now. Maybe we don't have to get up at 4:00 o'clock like grandma.

And it, sort of, turned out — maybe after having learned and enjoyed and really getting to know [the way things were done in America] — maybe sometimes I preferred, and I missed the way, I really, kind of [grew up]. But the one food that I — peanut butter and jelly on white bread! I just couldn't believe the combination. You know we had a lot of peanuts, and jelly jam. We had [those ingredients] all the time and we used [them] a lot [in Italy]. But peanut butter and jelly, and on a white bread! And, I remember Wonder Bread. Bread was like cake. Because we were used to homemade, country bread. And sometimes grandma made it once or twice a week. So it became even a little harder towards the end. But nonetheless, here you had this soft piece of bread. You put the jelly in there and it all became one. And the flavor's really delicious. To this day, I love it.

The next thing that really impressed me, because then I started cooking at home, was the packaged cake mixes. Making a cake for dessert with grandma — it was a project. First of all, because it was an extra — it wasn't necessary to keep you alive. But it was a special treat for the holidays, or whatever. So to make a cake, and grate the lemon, and grate the nutmeg, it was a big process, and all of this with grandma. Here, I had this box. I found this box, add an egg, add some milk and you have a cake. [Get a] mix, put it [in] the baking pan and you have a cake. So I was mesmerized by these different kinds of cakes — and chocolate cakes, and vanilla cakes and all kinds of icing and nuts, and all that. That's another thing that really kept me busy and intrigued me in the beginning.

Lidia Bastianich dishes on meeting Julia Child

You grew up making dinners for your family because your mother was working. When you were 24, you opened your first restaurant and you worked as a sous-chef. When you opened your second restaurant, you took the reins. What was it that attracted you about cooking in a restaurant for clients?

Well, I think it was, since I loved it, and it was something that I did for my family — to be able to engage complete strangers into your life and to enter into their life. Now, these people that came, they trusted what you cooked. They trusted you completely. Because to eat something that you don't know how it's been cooked, you need to have trust. And so I felt very special ... Especially [when] they liked my regional dishes, the ones like the polenta, the risotto, all that. I said, "Oh, I have something special that they want, that they would like." So I felt good, I felt important. I felt like I was giving them a new experience. Here I was, I was given a great opportunity to be an American. And this was one way of giving back. Bring my Italian heritage to my new American home, my family.

Fans might not know that you developed a very close relationship with Julia Child after she came into your restaurant and tried your food. Can share some of your memories with her?

Julia Child was a very unique person, a wonderful person. She had, I guess, somehow read about when I opened my restaurant, and I became "Chef Lidia." And she wanted to know, what was this woman: young, Italian, [what was I] doing different? [She wanted to know] what Italian-American cuisine was all about? Italian-American cuisine was tomatoes, meatballs, or whatever. I made also polenta, risotto. So, she came in with James Beard, right? These two towering figures, they were both very big. And they sit down, and she wanted to have risotto, mushroom risotto. And then afterward she wanted to learn how to make it and she wanted to go to her house. She came to my house and that's how the friendship started. And then she let me on [her] show, and that was the beginning of my TV career.

What Lidia Bastianich learned from getting to know Julia Child

Do you have memories of cooking with Julia Child at her house?

I do. At her house and even when her husband, Paul, was still there. Her kitchen, which is now at The Smithsonian, was the way it is. It's very convenient. Everything was very practical. And that was nice. And she was very curious. She wanted to know — not only that, she was always sticking her fingers into things trying to taste, to see, "Lidia, and this now?" She wanted to know. So she was very open in learning, but also open in sharing. She would say, "Oh, I would do it this way." And, "Oh, I thought it was done that way." So she was full of comments and we became good friends, I would say, until the very end, actually. I think I went to visit her a week before she passed, down in Santa Monica.

Do you have any particular recipe that she changed your perspective about how to cook?

Well, if you look at some of the French basics, the brulées, and the onion soup. But I profess the Italian cuisine. I don't begin to think that I ... but yes, yes. Yeah. Coq au vin. Yeah, okay, chicken. We eat a lot of chicken and we make a lot of chicken. Not exactly like that. So, certainly, I have tried things that she made and she made it look very simple on television, because that was her success.

Have you adopted much of her style when teaching people through television?

I think that was her success. And once I was on her show, we did two shows and then the producer said, "Okay, Lidia, you're pretty good. How can I show this?" Then, inevitably, I went to her, "What do you think?". She says, "Oh, Lidia you do for the Italian cuisine what I did for the French. Go ahead, you're going to be just great. " And she, kind of, helped me along. But I observed her. I observed how she was a real teacher. It was not about her showing off how much she knew or how much ... She wanted to make sure that the viewer, if the viewer gave her that half an hour, that the viewer gets something for it. And I remember, then I said, "You know, it's not about me cooking for me. I can take the viewer out there to the food." And you Americans love Italian food. I could take them and let them make Italian food in their house. Because Italian food, on its basis, is simple. It's all of the products: good products, and simple preparation. So, that's something that I took from her.

Lidia Bastianich discusses her favorite pasta shapes

You are gifting us with another cookbook very soon, "Lida's a Pot, a Pan, and a Bowl." In your cookbook, there is a recipe for an Italian version of a French onion soup –

That could have been a little bit of Julia's influence.

You hint at how the recipe was created. You say that that day, you had mushrooms in your fridge that you wanted to use. They became incorporated into the soup, and it was a success.

Yeah. I think people should think that way when they cook. I think a recipe, it's great, it's a great beginning. Reading it and following it ... you'll get a success if you keep following it straight. But I think that it's also a jumping off-board, using a recipe to make something ... changing it. If you don't like peperoncino, put [in] black paper. If you have those mushrooms, then add those mushrooms. The freedom of, kind of, being in control of the recipe of cooking and making those recipes your own. I think that's [important].

I saw that in my grandmother. Whatever the vegetables were or something, it's not that she pulled out a book. There were some basic, understood rules. And then she, sort of, did things within those rules. So, I think that that's important to convey and give the reader the freedom. Because you get a lot of, "Oh, I can't cook." Of course, you can cook! Everybody can cook. Just use your common sense. Yes, do follow a recipe. But feel free to create, and to use everything you have so you don't waste. So, I think, about, [showing] — "Lidia does it, we can do it." Adding those mushrooms, it turned out delicious, and I included it [in my book].

Something that we continually struggle with, no matter how many times people tell us how to do things, are pasta shapes. There are so many shapes for pasta –

One hundred and sixty or so. And they're always coming out with more.

From your perspective, is there a pasta shape we need to know about, or should be using more, or that we should not be using as much as we do?

I think, the basic shapes are all ... I mean, I love my spaghetti, I love my linguine. But then, I love also the tubular pastas, the rigatoni, the ziti. And then I like the curlycue pasta, the fancy new pastas that are coming out, like cavatappi, or farfalle. They all have different shapes, they have different textures. And they play a role because they all, kind of, carry the sauce differently. And it's also, I think, it's a new dish. It could be the same sauce. If you change the pasta, it's a new dish. And so, it's a way of making life, maybe, a little bit more interesting in the kitchen. So, for me, I like the cavatappi, but I do still like my simple spaghetti, or linguine or rigatoni.

The surprising ingredient you can add to your soup, according to Lidia Bastianich

Talk to us about the use of ricotta cheese. You use it in both cookies and in meat meatloaf in your new cookbook.

So ricotta cheese. We had goats, you have cows. Every, if you will, pastoral or farm culture has a milk-yielding animal to feed the family. And there's always milk leftover. And yes, you can make cheese, but that takes months. The easiest, the fastest [thing], is to make ricotta. My grandmother, we made ricotta almost every day. And so you have this wonderful, kind of, soft cheese — it's sweet — and this cheese can be [used] anywhere, from eating [it] raw with some honey and fruit, to whipping it up into a cream to make it the stuffing for a dessert, to making cookies with it. Then you can bake it, and make it solid, make it into an into cheesecake. You can make stuffing. It's, sort of ... it has different capabilities. When it cooks and it bakes, it solidifies, but it still leaves moisture.

So you can put anywhere, [even in] meat. The only one that I didn't use it [for] much was fish. But any kind of meats, or pasta, or desserts. Ricotta fits everywhere. In my meatloaf, I have it. Ricotta was one of those proteins that a lot of people had, and they found ways to use it. They just inserted it, even in soup. I know, during the springtime when the baby goats were born or whatever, we get a lot of milk. And grandma made a soup of wild herbs — nettles, and leaks and all that — and then she used the whey of the ricotta, where she drained the ricotta as a base for the soup. And those little pieces of ricotta that would float in the soup, it was delicious. I still make it.

Talking about sticking to the rules of Italian cuisine, one of the things you've said is that you think that adding cilantro to a dish is like sacrilege. Are there any other spices or that you stay away from when cooking?

No. I do think that I am into trying every spice. I have just been to India for the first time, and the mixture of all the spices they have there! And [those spices were also developed] to preserve the food so you could go back to [our conversation before]. But cilantro, somehow ... I think, they say [you're] genetically predisposed to not liking it or not being able to so ... For me, it feels like a mouthful of soap when I eat cilantro.

The one thing Lidia Bastianich always orders when she goes back to Italy

You go back to Italy often. There's such a regional richness in the food culture in Italy. But is there a certain dish or certain dishes you always look to eat when you visit?

The number one — because usually the flight comes in the morning — I love my cappuccino and my cornetto. I don't have breakfast on the plane or anything. As soon as I get down, [I get] that real taste to Italian coffee. I yearn for that. But otherwise, it depends, of course, on which region and what the season is. I mean, I'm going to be going next week. It's truffle season, and I'm going to have possibly truffles! I'm already yearning for it. So, I think, the seasonality of it, and the regionality of it. I think, what is the season? Are the wild asparagus coming in? I'm looking for the thing that will bring me back to my childhood memories and the season that will ... I mean, I always go in March because I want to go search for those asparagus that I remember as a child. I think it differs. It's not just one thing. But cappuccino, I have to have.

What's different about an Italian cappuccino for you?

There's an intensity in the coffee, number one. And then the "schiuma," the froth, it's not so frothy. It's more dense. And then the bubbles are very, very tiny. It's almost like a velvety cream, rather than the frothiness. So, when I'm drinking, the froth doesn't end up on my nose.

Can you give our readers any tips when they go to an Italian restaurant in the United States? Is there a dish that they should always stay away from if it's on the menu or is there a dish that they should always look out for?

I think, stick to the dishes, I guess, that you recognize somehow that are Italian. I think a lot of chefs do a lot of combinations, and textures, and add a lot of stuff. Italian cuisine is not a lot. Italian cuisine is simple and straightforward. Think about the seasonality. What's on the menu? Do they have these, let's see, tomatoes in January? Try to stay away from that, it's logical. So trying to follow the rules, of the Italian cuisine, even when you're at the restaurant.

Why Lidia Bastianich is publishing another cookbook

Are there concepts, Italian cooking concepts, that don't translate to English?

Well, if you speak multiple languages, like I do, [you find] that a certain word in a certain language will best express what you're thinking. So if you were in a group, in our house we speak three languages ... for us to finish one sentence in three different languages is okay.

But there are certain words in different languages that explain [something] better, maybe because that act or whatever [comes from] that language. One of the things that I always find ... hard to explain is when I make the risotto and the last step, when I sort of "mantecare" the butter and the cheeses. So "mantecare" has a specific meaning. It has a special meaning in Italian, and you can see already the cheese and the butter melting in the risotto, really becoming creamy. "Mantacare" is maybe "amalgamate." I use all kinds of words, but there's not one word that would say "Mantacare."

Lidia, do you have any advice for readers that are using your cookbook?

Sometimes we cook and we use 10 pans. [My grandmother] used to use one pan, one pot, one bowl, whatever. The concept, here, is to make those recipes all in one pan, or all in one pot. And the long cooking techniques, of course. They yield better, whether it's toasting or braising or whatever, in this situation. But, I think, think about a meal completely: not to just think about the meat, that's the main protagonist, and then [think about] the vegetables or whatever. Combine it. Vegetables are a big deal in Italian cooking ... So in this book, you'll find a lot of combinations in the balance of proteins and vegetables ... cooked [together], whether it's grazed all together, when it was baked all together, whether it's steamed all together. That was the point.

You've contributed so much to our general cooking knowledge already. Why another cookbook?

I think it's my 12th book or whatever. I like writing books, I like communicating. But in my process of my professional cooking, or my home cooking, I always think, when something happens "oh, I should share that ..." Because if I share it in the book, I share it in television, too. The television is an outpouring from the book ... So as I learn ... or as I discover new products, I want to share. You know, this book [goes back] to: "Grandma cooked in one pan." A lot of times I cook in one pan, and two. Usually, you see chefs [use] three, four pans, a mixer, a this, a that, up and down. And sometimes, I don't do that at home. This is what I'm going to have to share with the reader. The ideas for new books come ... out of a reality that I kind of discover [along the way]. Then as you dig, you find more things that you don't really speak out, but you have in you. So [I] try to dig those out and share.

How to start in the kitchen, if cooking scares you, according to Lidia Bastianich

You've talked about how cooking is therapeutic for you. Do you have any advice for people who find cooking stressful?

Yes, I think I do give that kind of feeling of confidence. They say, "Lidia you relax me ... you empower me ... you encourage me." And that's exactly what I would say is that everybody can cook something. Simple. Start with the recipes with three ingredients, four ingredients. And, you know, read the recipe ... and I'm sure it will be a success. And then you'll add to it, and you'll increase [your skills] and you'll grow. It's [about] getting the confidence. Also, you know, [it's about] knowing that cooking is a lot of common sense. You don't have to be a genius. A lot of common sense. If you're in the kitchen and if you're cooking and you're sense tells you, "Ah, don't do that, that shouldn't be ..." Then, most likely, your senses are telling you the right thing. Trust yourself in the kitchen. And start simple. If it doesn't turn out good, if you burn it, it happens to everyone. It happens to me.

Do you have a favorite three or four-ingredient recipe?

Yeah! Oh yeah, absolutely. Marinara sauce, you know, people just love that marinara. So, you have some plum tomatoes –- all fresh things — yes, fresh tomatoes if it's in the summer, but otherwise canned plum tomatoes. Whole tomatoes, not the mush. Sliced garlic, good olive oil, you brown it — a little bit with pepperoncino, brown that. You squash the tomatoes, throw them in the [pan]. Give it a boil. [Wait] 20 minutes. Put in two basil leaves. You got yourself a marinara. So, garlic, oil, pepperoncino, plum tomatoes, and basil. And 20 minutes. Make it, try it. You'll see.

Make sure to pre-order and purchase Lidia Bastianich's new cookbook, "Lidia's a Pot, a Pan, and a Bowl." For more, daily inspiration from Bastianich, follow her on Instagram.