12 Mistakes Everyone Makes With Canned Tuna

Hungry? Need a meal in a pinch? Few food items are as convenient and nutritious as canned tuna. It's packed with protein, omega-3 fatty acids, vitamins B12 and D, and minerals (per WebMD). Not to mention, a tuna salad sandwich or tuna melt are pretty tasty. The perks don't stop at the nutrition and flavor, though. Canned tuna — especially light tuna packed in water — is very affordable.

According to Seafood Health Facts, the five primary commercial tuna species are albacore, bigeye, bluefin, skipjack, and yellowfin tuna. When you grab a can of tuna from the store shelf, you're buying albacore tuna (white tuna) or skipjack tuna (light tuna). Canned albacore tuna is more expensive, but the price also varies in how it's packed. The flaked fish is canned in either oil, brine, or spring water.

But even if you're a canned tuna connoisseur, you're likely committing some blunders with this convenience food. Do you know how to store it properly? Is your sandwich soggy because you didn't drain it properly? Are you eating too much of this protein powerhouse? Take a look at these and other common mistakes everyone makes with canned tuna.

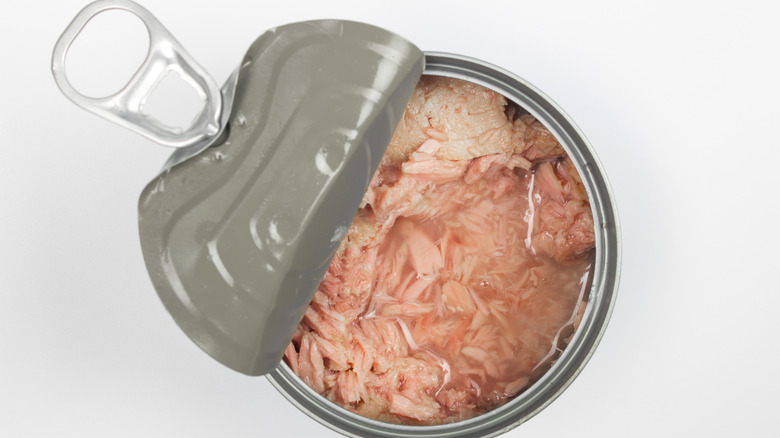

1. Not draining the tuna properly

Should you drain canned tuna? Technically, you don't have to drain the water or oil from a can of tuna to enjoy it. Most people don't enjoy soggy sandwiches, though, so draining your tuna is the common-sense solution to that problem.

But draining tuna is beneficial for more than just removing excess liquid. It has a nutritional impact, too. Tuna packed in oil, for instance, has twice the amount of calories as tuna packed in water. According to the USDA, a can of tuna in oil has a whopping 317 calories compared to the 150 calories from tuna in water. So, removing the oil reduces calories by quite a lot. Both water and oil-packed tuna also contain sodium, which can be reduced by eliminating the liquid.

According to Home Cook World, you have three options for draining tuna. The first is opening a small hole in the can, flipping it upside down, and allowing gravity to do the work of pulling the liquid out. The second involves removing the lid from the can entirely, placing the lid back on, and using your hands to squeeze on both sides of the can to expel as much oil or water as possible. The third technique is as simple as dumping the canned tuna into a colander. Note that you may need to press down on the fish in the colander to press out excess liquid. Once your tuna is drained, eat up!

2. Tossing it too soon

Take a second to think before you throw out that dusty tuna can in your pantry or that opened tuna you stored in the fridge a few days ago. Some of us tend to be squeamish when it comes to seafood, so it's no wonder tuna is often tossed too soon for fear of it going bad. The good news is that canned tuna can be stored for longer than you think.

A can of tuna can be stored in the pantry for up to five years, according to the USDA. The best place to store it is in a cool, dry place away from sunlight. However, if you are catching and canning your own tuna, you shouldn't keep it for more than a year.

But what about the leftover tuna you put in the fridge? The North Carolina Division of Public Health recommends storing tuna in an airtight container in the refrigerator for up to three days. The same holds true for tuna salad — you can enjoy those delicious sandwiches for three whole days. However, if you added the canned tuna to a casserole or cooked dish, you can safely store the leftovers in the freezer for up to two months.

3. Storing canned tuna near heat or light

You may want to rethink the location of your tuna stash if it is stored above your stove or on open shelves near a light source. Foods can be spoiled or degraded by both heat and light. The University of Minnesota Extension recommends not exposing canned goods to temperatures above 100°F. High temperatures increase the risk of food spoilage, but even temperatures of 75°F and above can cause nutrients to be lost. Tuna should be stored in a cool, dry area below 85°F — preferably between 50°F and 70°F — to keep it in its prime.

According to the National Fisheries Institute, room temperature is the ideal temperature. Temperature and light are important factors in proper tuna storage, but they are not the only factors. To prevent crushed or rusting cans, the Institute recommends storing canned fish on a shelf instead of on the floor. In addition, you should store your oldest tuna cans at the front and your newest ones at the back of your pantry as you replenish your supply. Using the oldest cans first will reduce the chances of your canned goods expiring before they're consumed.

4. Storing leftover tuna in the opened can

Despite what you might have heard, refrigerating leftover food in a can does not pose a food safety risk. According to the USDA, refrigerating food in a can after it is opened is perfectly safe, but it may affect its quality and flavor. Hence, the agency recommends sealing leftovers in plastic or glass containers.

It is important to note, however, that the safety concerns about Bisphenol-A (BPA) aren't entirely unfounded (according to Epicurious). The chemical is used inside the lining of metal cans and in many food storage containers. Newsweek reports that the chemical mimics estrogen and is associated with diabetes, cognitive issues, and fertility issues.

Canned tuna, on average, contains about 140ng/g of BPA (per Atuna). It would take 25 cans of tuna to exceed the EU's maximum guideline for this additive. The presence of BPA at this low concentration is considered harmless. However, according to the Environmental Defense Fund, Americans take in 5,000 times the amount of BPA that the European Food Safety Authority considers safe. That may be reason enough to look for BPA-free cans.

Essentially, the best reasons for transferring your leftover tuna to another container are to protect your fridge from taking on a fishy smell and to preserve the quality of the fish. Nevertheless, if you're a rebel and decide to store it in a can anyway, seal the can with plastic wrap. This will keep the flavor (and odor) with the fish.

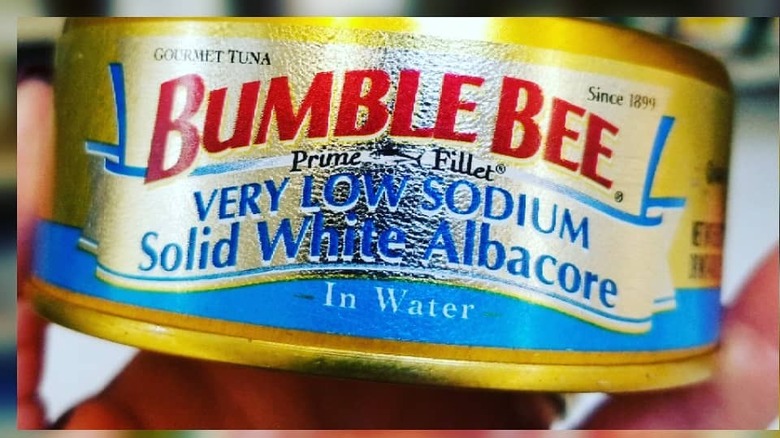

5. Not choosing a low sodium option

Compared to fresh foods, canned foods contain more sodium. On average, canned tuna contains 247 mg of sodium per 3-ounce serving, according to Healthline. That amount is a little more than 10% of the Centers for Disease Control's recommended dietary reference intake for sodium, which is 2300 mg per day. If you're on a low-sodium diet, this is concerning. But watching your sodium doesn't mean that you have to give up your tuna, as long as you follow a couple of guidelines.

When buying tuna, look for low-sodium varieties. It sounds easy, doesn't it? But according to LiveStrong, labels can be tricky. You may think that tuna packed in water, for example, is just tuna and water. That often isn't the case when you examine the list of ingredients where you'll find salt was added. You should instead look for labels that state "no salt added," "low sodium," or "reduced sodium."

Don't give up hope if you are unable to find reduced sodium tuna at your local grocery store. An American Dietetic Association study found that rinsing canned tuna in water for three minutes reduces sodium content by 80%. That's a significant reduction for only a little bit of effort.

6. Eating too much canned tuna

Is it possible to eat too much tuna? As far as the Food and Drug Administration is concerned, the answer is YES. The same is true for all fish, not just tuna. The FDA recommends eating two to three servings (or 8 to 12 ounces) of cooked fish per week. But what's the problem? Fish, after all, is packed with vitamins, minerals, and omega-3 fatty acids. However, the thing you need to watch out for is mercury. While canned light tuna is a low-mercury option you can enjoy two to three servings of, albacore tuna is higher in mercury and should only be enjoyed once a week. We'll discuss that in more detail later.

There are a couple of ways you can make sure your portions are just right. You can measure 4 ounces of tuna using a kitchen scale, after zeroing out the weight of your dish. No kitchen scale? No problem. Just look at your hand — 4 ounces is about the same size and thickness as your palm.

7. Not inspecting the cans

It may seem that canned food can survive anything, including the apocalypse, but that's not the case. Do you regularly check the dates on the canned food in stores or as you pull it out of your pantry? Do you look for dents, rust, and bulges? If not, it's worth the few extra seconds to avoid potentially eating food that has gone bad or degraded in quality.

When you're inspecting cans, take note of dates, dents, bulges, rust, and leaks. When it comes to the product date, it's more about food quality, not an indicator of food safety (per the USDA). Cans have a "best by," "use by" or "sell by" date on them. Ideally, you'll use canned foods before the "best by" date. But if some time has passed, it's still safe to eat as long as the smell and color are still normal. The "sell by" date is helpful for grocery stores and is usually years from when you find the can on the shelf.

Once you've confirmed the date is still valid, look for signs of damage to the can. A leak is serious enough to throw the can away immediately. Bulges or rust may also indicate leaks, especially when they're near the seams. That means any can that's bulging or rusty gets tossed straight into the trash bin, too. As far as dents are concerned, small ones aren't necessarily a problem. However, the USDA recommends discarding cans with dents that are large enough to sit your finger in.

8. Not choosing sustainable and environmentally friendly options

For those concerned about sustainability, it's important to know where your tuna comes from and which fishing methods were used to get it. In the 1980s, these issues came to the forefront when the public became aware that dolphins were dying as bycatch in the tuna nets. Fisheries began using fish aggregating devices (FADs) to minimize dolphin bycatch, but unfortunately, other fish species are aggregated and caught along with the tuna.

Still, the dolphin-safe label is important to many people. The standards to use the label are that no dolphins are killed while fishing for tuna and that any dolphins caught in the nets are set free without causing injuries. To take it a step further, look for terms like pole-caught, FAD-free, and school-caught to support brands that minimize the catching of other marine species. Seafood Watch lists several brands of tuna that get their fish from environmentally friendly fisheries, such as American Tuna and Wild Planet.

9. Not branching out with canned tuna

Plain ol' tuna straight from the can may be okay if you're a cat or if you're looking for a quick meal while hiking or camping, but otherwise, there's no reason not to jazz it up. Try tuna salad for delicious sandwiches or lettuce wraps, a tuna melt, tuna casserole, or even tuna pot pie.

There are so many ways to make tuna salad, so switch up your usual recipe for some variety. Our simple tuna salad recipe requires only eight ingredients, and you'll have a tasty sammie ready in about six minutes. Canned tuna, red onion, celery, pickles, crispy fried onions, mayo, salt, and pepper combine for the perfect tuna salad with a little bit of crunch. It's even better when you allow it to sit in the fridge overnight.

Chicken pot pie is overrated. It's time you try tuna pot pie to use up some of your canned tuna stash. The crust is refrigerated biscuit dough, making this dish super easy to execute. Frozen veggies and canned tuna are combined into a creamy mixture along with a delicious blend of herbs and spices. It's ready in just 30 minutes, making it great for a busy weeknight.

10. Not choosing lower mercury options

Pregnant women and young children need to be especially careful about mercury consumption, but it's something we all need to be aware of. Mercury makes its way into the atmosphere via natural and manmade means and gets into our rivers and oceans when it rains. When it enters the waters, it makes its way into the food web.

What's the concern with mercury? The World Health Organization reports that it has toxic effects on babies in utero, lungs, kidneys, and several bodily systems. The main exposure route is by consuming methylmercury from fish and shellfish. The presence of mercury isn't a reason to give up canned tuna, though. Following some simple guidelines will help you minimize your consumption of the stuff.

According to the Environmental Defense Fund, the mercury level in albacore tuna is three times higher than light tuna. The Harvard School of Public Health recommends limiting albacore tuna to once per week, while you can enjoy light tuna twice per week.

To further manage your mercury intake, look for labels that say low mercury. Safe Catch Tuna, for example, tests each tuna for mercury content. The brand boasts that its limit is 2.5 to 10 times stricter than the FDA's.

11. Using tuna that's gone bad

Sometimes, we take risks with our food. But taking chances on bad tuna is, well, risky business. Suppose that you found a can of tuna in your pantry that's just past the "best by" date. It's probably still good as long as the exterior of the can is free of bulges, rust, dents, or leaks. Opening the can tells the tale.

Opening a can of food is usually uneventful. But if it spurts liquid upon opening, that's a sure sign that the tuna is not safe for consumption. According to the USDA, spurting liquid can indicate the presence of toxin-producing bacteria, which are very dangerous.

Toss foul-smelling tuna in the trash. We know what you're thinking — fish always smells bad. That's true, but if you eat tuna on a regular basis, you know what it normally smells like. If the scent is off, trash it and clean up the area where you opened it. Examine the color if the tuna passes the smell test. Tuna is typically pink or light tan color (per Washington Post). Discolored meat that's dark brown, green, or black, gets thrown out.

12. Using only water-packed tuna

While tuna in water saves on fat and calories, you may be missing out on flavor. When a Reddit user in the Ask Culinary community asked for advice on improving their tuna salad, several members remarked that tuna in olive oil is more flavorful than water-packed tuna. Many Quora users reflect those sentiments, noting that not only does the oil yield better flavor, but it preserves the texture of the tuna as well, keeping it firmer.

Should you buy oil-packed tuna instead? That depends on a couple of factors (per Clean Plate). Use tuna packed in water if you're going to dress it up with heavy ingredients like mayo and onions, such as in your typical tuna salad. The real flavor difference is noticeable when you enjoy it over a green salad or mixed with some pasta. For those recipes where you want the tuna flavor to shine through, use oil-packed tuna.